Sweat and Tears

An integral part of the anti-colonial narrative, football is a story of our missed tryst with destiny

Sudeep Paul

Sudeep Paul

Sudeep Paul

Sudeep Paul

|

13 Aug, 2021

|

13 Aug, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Sweat1.jpg)

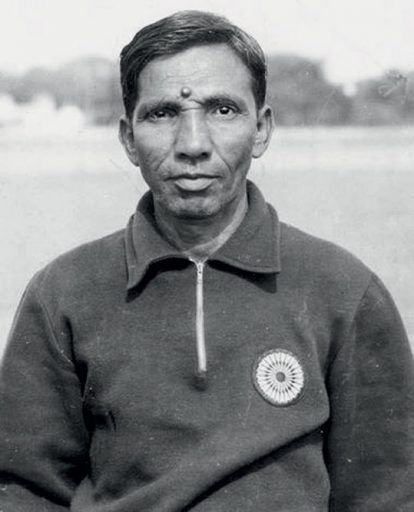

Gostha Pal's statue near the Eden Gardens in Kolkata

ON A SULTRY summer’s evening in the early or mid-1990s, I was reading about the strangest of fouls in football in the Bangla magazine Anandamela with the radio on. I don’t remember the programme but the station must have been BBC. For, Bobby Charlton suddenly came on air and talked about the ‘local’ advantages of any host team anywhere in the world: “Well, you play India in Calcutta and, you know, it’s really difficult.” Or something to that effect. But the example the England legend instinctively picked was India in Calcutta. Charlton was stuck in time. What he said was what he remembered of Indian football. We, on the other hand, had recently endured PSV Eindhoven thrashing the Indian national team at the rate of 7:0 to 8:0.

Implied in Charlton’s statement was, of course, the fact that a team like India, without home advantage, weren’t much of a challenge. Nevertheless, even in the 1990s, coaches of visiting European or South American clubs would notice Krishanu Dey and ask their Indian counterparts why, with a player like Krishanu, India did not play in the World Cup. The answer, whenever provided, would never be adequate. Did we have only one Krishanu? Perhaps. But near the twilight of Krishanu’s career, IM Vijayan was rampaging as one of Calcutta’s own, the ‘maverick’ Sudip Chatterjee had recently retired, and Bhaichung Bhutia had already exploded on the scene.

In the 75th year of independence, football remains an Indian tragedy. There was no mockery in Krishanu being called the “Indian Maradona”. Anyone who remembers his dribbling and dodging, his goals from tight angles and his curls, would acknowledge that it was Krishanu’s misfortune to be born in a land of no football hope. There was no mockery either in India long ago being known as Asia’s Brazil. Given the pace of the game back then, Indian legs were still as fast as South American ones, and Indian feet were often more skilled than European ones. This truism might have held despite the changes in the game, if only we had not fallen through the crack and disappeared.

The beginning of the tragedy happened to be the pinnacle of Indian football. The 1950 World Cup. That’s not contrafactual, even if the so-called ‘golden era’ for the national team followed that ignominious missed tryst with destiny. Indians played barefoot. FIFA wouldn’t allow that. Thus, the story went, India opted out of a World Cup it had automatically qualified for after the withdrawal of the other Asian teams. India would never qualify for a World Cup again—and for four generations since we have lived with that spiel. The technicality is true. India couldn’t have played barefoot as per FIFA regulations in place after the 1948 Olympics. But it wasn’t as simple as that. Shailen Manna and a few others had gone on record that the barefoot disqualification was just an excuse propagandised by the All India Football Federation (AIFF) to absolve itself. There was an overall lack of resources; the trip to Brazil would have been costly. But the AIFF seemed to have never grasped the significance of what a World Cup slot meant. And nobody could have imagined that it would never happen again.

Of late, there’s been a rather ludicrous debate whether a lack of funding from Nehru’s Government had forced Indian players to hit the pitch barefooted at the 1948 Olympics. The lack of funds and foresight was not confined to football. But Nehru could not fairly be blamed for the lack of boots, or studs. To do so would, in fact, obliterate the pre-Independence history of football in India. The irony is that we still take pride in our pseudo-socialist ‘povertarianism’ but not much in that history. And yet, there is much to be proud of in the barefoot beaters of our former colonial masters who had introduced us to the only universal sport (as they had in South America but with a vastly different outcome although no one could have foreseen that in the 19th century).

We still take pride in our pseudo-socialist ‘povertarianism’ but not much in those barefoot beaters of our former colonial masters. As we celebrate the revival of Indian hockey this year, it is only fitting that we also celebrate these men who had triumphed against all odds

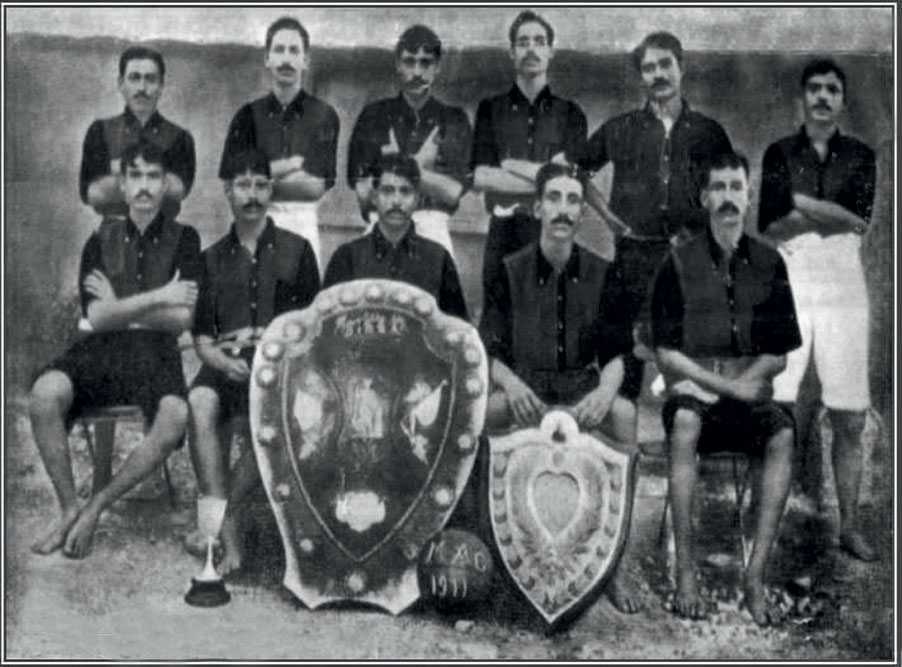

On July 29th, 1911, Mohun Bagan, founded in 1889, became the first all-Indian team to lift the IFA Shield by beating the formidable East Yorkshire Regiment 2:1 in Calcutta. There’s very little literature extant but Shantipriya Bandopadhyay’s Cluber Naam Mohun Bagan (The name of the club is Mohun Bagan) is a handy reference. Reportedly, the crowd swelled above 60,000, with many people making the journey from eastern Bengal (Mohun Bagan was still their club). A few days later, the Manchester Guardian opined: “A team of Bengalis won the IFA Shield in India after defeating a crack British regimental team. There is no reason…to be surprised. Victory in association football goes to the side with the greatest physical fitness, quickest eye and the keenest intellect.” These lines, referenced in the book, were generous even as they exposed a coming to terms with reality. What the paper didn’t grasp, or chose to overlook however, was the most intangible factor of all: it was more than physical fitness or a sharp eye. It was anger, fuelled by a lived experience of discrimination. All squared off on the great level playing field of football despite the referees. (A particularly notorious match, in 1936, was Gostha Pal’s last, when a biased referee reportedly blew the whistle every time a Bagan player entered the penalty area of the Calcutta Club side. The IFA took the protesting Bagan players to task and prompted “ Chiner Pracheer”—the Wall of China—to abruptly retire.)

Less than a decade later, in 1920, a group of aggrieved club administrators would establish East Bengal (the youngest of the Big Three in Calcutta after Bagan and Mohammedan Sporting); the club so named not so much to provide a sporting vent for the East Bengali population in Calcutta but to celebrate the founders’ antecedents. But in time, East Bengal became precisely that—a club supported by East Bengali migrants and, post-1947, by refugees from East Pakistan, with a fixation on Mohun Bagan, which had lost its pan-Undivided Bengal identify and support base to shrink to a club of the native West Bengali population. East Bengal, riding a narrative of discrimination within discrimination, would soon eclipse Mohun Bagan and become Calcutta’s most successful club although, with its rather parochial name and latter-day credentials, it never enjoyed the national appeal that Bagan did, especially before Independence. The club won its first IFA Shield in 1943 and till date retains the distinction of winning the most—a total of 29. It remains, along with Bagan, the most successful team in the Durand Cup, Asia’s oldest existing football tournament, with 16 titles.

The history of Indian football (played by all-Indian sides) before Independence, and for a long time after, is largely the story of these three clubs given their pedigree and Bengal’s near-monopoly of the Santosh Trophy till it was broken in the 1960s. Three factors ensured Indian football never recovered the status it once enjoyed after the national team’s second Asian Games Gold in 1962 (its best performance remains finishing fourth at the Melbourne Olympics in 1956). The dazzling decade-plus of 1951-1962, with Chuni Goswami (India’s captain at the 1962 Asiad), PK Banerjee and the versatile Tulsidas Balaram at the helm, ended with the death in 1963 of legendary national coach Syed Abdul Rahim—the man behind the near-Bronze in Melbourne in 1956 and the two Asian Games Gold in 1951 and 1962. A football thinker, Rahim was far ahead of his time not only in the Indian context but also by most standards of frontline football philosophy. Incidentally, a biopic of Rahim is set for release later this year. His successor Alberto Fernando had reportedly said after a trip to Brazil in 1964 that what he had learnt from Rahim a decade earlier was only then being taught in Brazil. Without the individual genius of Rahim and the departure of the likes of Chuni and Balaram, the AIFF was clueless and apathetic. This was, of course, the biggest and longest-term factor behind India’s decline and fall. But the last straw was the cricket World Cup of 1983.

Matters were not helped by the fact that the popularity of football was mostly confined to four states—West Bengal, Punjab, Goa and Kerala—and the Northeast. For a while, it wasn’t paranoia to believe that all that would remain of Indian football was the statue of Gostha Pal near the Eden Gardens. Which is why, despite the mixed results, one cannot but celebrate most things that have changed in Indian football of late. One, football is being invested in, albeit nowhere near adequately, with training academies, facilities and sponsorship. Two, both the men’s and the women’s teams have been making more than an effort. The women’s team stands at 57 in the world rankings, having reached a best ranking of 49 in 2013. The men’s team has slipped from 97 in 2018 to 105 but that’s a far cry from 171 in 2014. The men had almost qualified for the final round of the 2002 World Cup qualifiers, missing out by a point to the UAE. They returned to the Asian Cup in 2011after more than a two-decade absence. And the youth teams have been performing quite impressively. While the AIFF is wiser and older, braving up to host the U-17 FIFA World Cup in 2017 was the correct decision. As was creating the Indian Super League to follow up on the I-League. Three, thanks to these changes and the broadcast of all major global football tournaments and leagues, the sport has a following today beyond its old bastions. In retrospect, Doordarshan’s sudden change of heart (and head) in deciding to telecast the entire 1986 World Cup in Mexico was one of its wisest calls ever.

The dazzling years of 1951-1962 ended with the death in 1963 of national coach Syed Abdul Rahim. A football thinker, Rahim was far ahead of his time not only in the Indian context but also by most standards of frontline global football philosophy

Sunil Chhetri’s appeal on social media in 2018 to abuse and criticise the national team but to go and watch them play summed it all up while underscoring the lifeblood of every football player—support from the stands.

FOOTBALL WAS the original colonial sport that had quickly become a vehicle for anti-colonial payback. It was played by ordinary people and attached itself to the narrative of the freedom struggle seamlessly. As we celebrate the revival of Indian hockey this year, between a Euro and a Copa America and the World Cup next year, it is only fitting that we also celebrate those men in maroon and green, and later in red and yellow, who, along with their rivals in black and white, had scripted a tale of triumphing against all odds.

That it all began in Calcutta was an accident of history. Where else but in the old colonial capital? But the crop found passionate soil. It was something of that mass passion that Pelé experienced firsthand in 1977 when Mohun Bagan drew 2:2 with his New York Cosmos before a crowd of 80,000 spilling from the stands. It was the same passion that suddenly swelled and caused one of the most embarrassing episodes of crowd mismanagement in football history in a non-competitive capacity when Diego Maradona visited in 2008. When Messi led Argentina against Venezuela in a friendly in 2011, the referee was reportedly star-struck. Well, there’s an anecdote, from the late 1980s or early 1990s, of a young footballer asking PK Banerjee (or was it Subrata Bhattacharya?) after watching a visiting foreign club train: “If that’s how they run with the ball, how are we going to play?” The coach replied: “Parle khelbi, na parle dekhbi (Play if you can, otherwise just watch).” A summary of Indian football in five words.

That anecdote had spread by word of mouth in a still-industrial town now known for its high-end residential towers, a few kilometres to the southwest of Kolkata city, which had given India several of its most gifted footballers. As a former resident of that town, I live in hope that this prolonged Indian tragedy could still end. It’s been 71 years. Maybe, there’s another tryst with destiny in the offing well before we celebrate the centenary of Independence.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

Gukesh’s Win Over Carlsen Has the Fandom Spinning V Shoba

Mothers and Monsters Kaveree Bamzai

Nimrat Returns to Spyland Kaveree Bamzai