Congress 2022: War Dance in the Puppet Kingdom

Congress wants a regent, a placeholder for Rahul Gandhi. But who can combine political sagacity with a saintly heart? Ashok Gehlot, the loyal one, has weakened Sonia Gandhi at a vulnerable moment. If she relents, the aura of command gets blown apart. Congress has become a puzzled jigsaw rather than a jigsaw puzzle, a combination of small cardboard pieces that no longer add up to a coherent picture

/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Congress1-1.jpg)

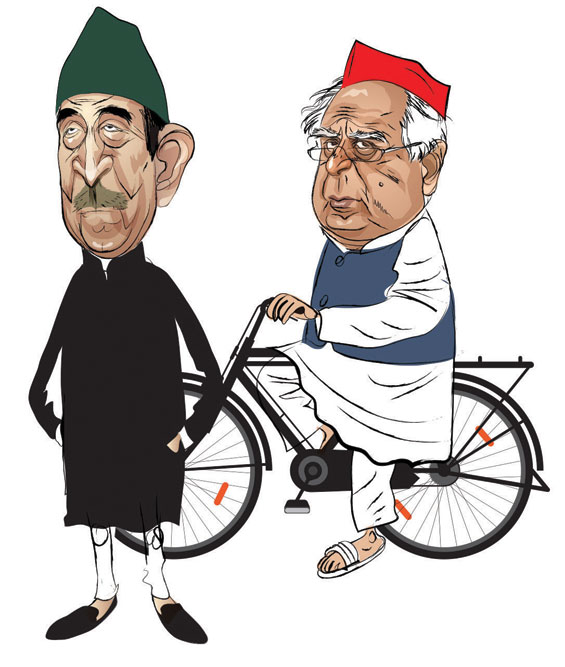

(Illustrations: Saurabh Singh)

AN AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP CANNOT sustain a democratic process. That was and remains the fundamental flaw in the tattered exercise to find the first Congress president outside the Nehru-Gandhi family in a quarter century through a pretend process. It is neither an accident nor a surprise that this election, scheduled for October 17, should have imploded on the starting line.

Basic Question No 1: Why did the chosen hero of the hour, Ashok Gehlot, a man earmarked to enter the textbooks as successor to Sonia Gandhi, the majestically unmoved leader for more than two decades, prefer a regional job in Jaipur to the grand national honour offered in Delhi? Gehlot did not become Sonia Gandhi’s preferred nominee through a lucky dip. He was recognised for the kind of loyalty that ensures upward mobility in a dynastic culture. A thin illusion of impending contest was fed into the media by candidates searching for publicity rather than a post, but there was only one candidate who mattered: the nominee blessed by an imperial nod.

Gehlot was loyal, but not naïve. He knew that Sonia Gandhi and her heir Rahul Gandhi wanted a figurehead rather than an empowered figure, an underling good at taking dictation rather than a chief executive. Moreover, he rather liked being chief executive, having discovered its advantages during two spells as chief minister of Rajasthan. Gehlot turned out to be more astute than the Congress ruling family had bargained for. He moved before he could be pushed. He was ready, he said, to wait in a holding room for Rahul Gandhi to claim his mantle, as long as he could continue as chief minister. There was nothing breathtakingly radical in his proposal. All Congress prime ministers since Indira Gandhi, except Manmohan Singh, have simultaneously held the post of party president.

Basic Question No 2: How did the dynasty get blindsided, and then ambushed?

Years of unquestioned obedience take their toll. Imperceptibly, confidence mutates into overconfidence, breeding complacency. The leader marks the calendar with a wishlist, and every wish becomes a command. Institutions created for shared decision-making become a charade played out by nodding heads who are little more than jerky puppets on a string. The strings may be silken, and barely visible, but they hold such a show together. Dissent is dismissed as a passing phenomenon. And so, when Ashok Gehlot expressed unhappiness at being removed from Jaipur, it was initially viewed by the high command as passing petulance. Intermediaries effectively told him to grin and bear it, probably reminding him that he was fortunate enough to get some form of compensation. After all, his election, or selection, as Congress president was a foregone conclusion. Nothing, then, to worry about.

Gehlot had other ideas. Those with other ideas in Congress have generally had the gumption to keep the ideas to themselves. Such self-censorship started to crack after Kapil Sibal and Ghulam Nabi Azad began to ask questions on behalf of a group of 23 old-timers. Both Sibal and Azad are out of Congress. Sibal is back in Rajya Sabha with the help of Akhilesh Yadav, wafted by larger notions of justice, as befits an excellent lawyer. Azad has summed up a lifetime’s frustrations in the name of his new outfit, Democratic Azad Party. The implications are obvious. Unlike Congress, his party is democratic. And he himself has finally lived up to his name and become ‘Azad’. He seems to be enjoying his liberation. As for the questions that Sibal, Azad and the insubordinate group of 23 raised, they are stored in the well-stocked cupboard reserved for irrelevant files at the headquarters of the All India Congress Committee.

Gehlot’s fault was not ambition. That is a human right in any power game. Gehlot’s sin was treason. He achieved something more dangerous than defiance; he succeeded. A successful rebel is a greater threat to any dynasty than a recognised enemy. That is an abiding law.

The bewildered anxiety of Ajay Maken, sent to implement Delhi’s orders, was a stark and startling exposé of just how Congress functions. He expected perfunctory proceedings; he was hit by an insurgency. He could not believe that an overwhelming majority of the state’s MLAs preferred Gehlot to dynasty. The pillars of every assumption began to crumble around him when they did not appear at the legislature party meeting on Sunday, September 25, for what was meant to be a routine show of hands in support of Sonia Gandhi’s decision to anoint Gehlot’s rival Sachin Pilot as the next chief minister. Sonia Gandhi asked Maken to speak to the MLAs individually on the assumption that they could be either induced or bullied in the absence of physical solidarity. They refused. As for Ashok Gehlot, he played the game with a safe-distance insurance policy. What was he to do, he suggested; this was the will of the local party. It did not want Pilot as its navigator.

Gehlot was loyal, but not naïve. He knew that Sonia Gandhi and her heir Rahul Gandhi wanted a figurehead rather than an empowered figure, an underling good at taking dictation rather than a chief executive. He rather liked being chief executive. Gehlot’s fault was not ambition. Gehlot’s sin was treason. He achieved something more dangerous than defiance; he succeeded

As Maken left Jaipur, shaken more than stirred, he repeated to the media his message to the rebels: “We said we will convey your feelings to Sonia Gandhi and she will decide on a way out. But they insisted that their three conditions should be part of any resolution we pass. But we told them, in the history of Congress, there has never been any conditional resolution. There is always a one-line resolution handed to Sonia Gandhi and then decisions are taken.”

For Ajay Maken, the history of Congress begins with Sonia Gandhi, and party literature consists of one line.

It is tempting, albeit a trifle ambitious, to predict what might happen over a turbulent fortnight in a clash between a fading autocracy and a tense satrap. Nerves are notorious for snapping. The stakes are high. But some facts are indisputable. If Sonia Gandhi relents, the aura of command gets blown apart. Gehlot has crossed the Rubicon. There can be only one winner now. The bridge between the two was built on trust, and that has disappeared with yet another tide ripping through history’s delta.

It was obvious by mid-week that Sonia Gandhi was anxious for some face-saving compromise through which she could maintain that her authority had not been diminished even as she found ways to appease Gehlot. When the veteran AK Antony is summoned from retirement in Kerala for consultations, you know this is a crisis in capital letters. To paraphrase William Wordsworth: “Ahmed Patel! thou shouldst be living at this hour….”

Patel, Sonia Gandhi’s brilliant human resources director, might have been as bereft of a solution, but he would not have permitted the confusion that overtook the high command. Tuesday, September 27, saw a pandemic of mixed signals. Maken, who had angrily dismissed Gehlot as undisciplined was given a temporary time-out while other Congress colleagues hinted that Gehlot could get his way if he returned to the game. This did not seem very persuasive since the party also shot off showcause notices to two of Gehlot’s principal aides, Shanti Dhariwal, a minister, and Mahesh Joshi, the chief whip. Perhaps it was a case of trying to bribe the rebel general while hanging his troops.

Both Sibal and Azad are out of Congress. Sibal is back in Rajya Sabha with the help of Akhilesh Yadav. Azad has summed up a lifetime’s frustrations in the name of his new outfit, Democratic Azad Party. He has finally lived up to his name and become ‘Azad’. As for the questions that Sibal, Azad and the insubordinate Group of 23 raised, they are stored in the well-stocked cupboard reserved for irrelevant files at the headquarters of the all India Congress committee

Sonia Gandhi cannot risk double jeopardy. Nor will she ever forget that Gehlot has weakened her at a very vulnerable moment. Gehlot cannot continue in Congress except as a wasting has-been. He might get a token decoration, but none of his most loyal MLAs will get a ticket in the next election.

It does not require the brains of Chanakya to suggest that Gehlot’s only sensible option is to create a regional party. Rajasthan has a strong sense of identity, emotive pride, and vigorous history, but the state has never had a regional party that could exploit this terrific dynamic. Gehlot has demonstrated that he is not going to be a puppet, which should resonate well with local voters. There are enough precedents in other states for such a course of action. Most regional parties are by-products of a receding Congress, which survives in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh because it is the only alternative to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

GIVEN THE SHAMBLES of September, it would be safe to suggest that Congress is not going to return to power in Rajasthan in any hurry. As the casualty rate picks up, this may change but the biggest loser so far is the impatient young man who knew how to start a rebellion but not how to end it, Sachin Pilot. He triggered the instability in the hope that some two dozen MLAs, abetted by the dynasty in Delhi, could make him master of Rajasthan. He could not see, despite the growing mass of evidence, that the ruling family was not making all the rules anymore.

Perhaps he should have taken time out to learn a little about the history of his state. What we call the Mughal Empire was in fact a Mughal-Rajput alliance from the time the emperor Akbar reached out to Raja Bhagwant Das of the Kacchwaha family of Amer. Raja Man Singh fought over 60 wars for the emperor, across the compass, and was trusted so highly that he led the army to Kabul to suppress the rebellion of Mirza Hakim, Akbar’s brother. But when the empire crumbled after Aurangzeb’s ill-conceived policies, the Rajasthan principalities were the first to recognise weakness, and started to become autonomous from the 1710s. They were wise, which is why they survived.

If the political season gets any more bizarre, Sachin Pilot might launch his own regional party. Anything is possible in a meltdown.

Viewed objectively, the Rajasthan government has imploded, and the state’s governor would be well within his rights to dissolve the Assembly and order fresh elections, probably for this winter, along with Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh.

Congress is not going to return to power in Rajasthan in any hurry. The biggest loser so far is the impatient young man who knew how to start a rebellion but not how to end it, Sachin Pilot. he triggered the instability in the hope that some two dozen MLAs, abetted by the dynasty, could make him master of Rajasthan. He could not see that the ruling family was not making all the rules anymore

Gehlot may have achieved more than he expected. According to the fluid and constantly wavering grapevine at the time of writing, Congress veteran Kamal Nath has also conveyed that he would rather be a potential chief minister in Bhopal than a signaturist in Delhi. [Maybe “signaturist” does not exist in any dictionary, but it is a good word to add to the lexicon. It means anyone ready to sign on command.]

In the old days when royalty insisted on genes over genius, and then enlisted the help of divinity to justify the irrational, a vacuum caused by a child or childish heir was filled by the appointment of a regent. It was a difficult job. The regent required the skills to manage an administration and the temperament to abandon what he had preserved on a signal from the heir apparent.

Congress wants a regent in 2022, a placeholder for Rahul Gandhi. But how many are there in the upper echelons who combine political sagacity with a saintly heart? Sonia Gandhi might end up kicking the party elections into the long grass of the future and stick with the status quo. She may not be able to do much about the earthquake in Jaipur, but that would help contain the seismic tremors by sending the problems underground once again.

The Congress decline that started in the 1990s accelerated after 2014. In an anomaly beyond comprehension, those who were at the helm became stronger as the catastrophe of 2019 followed the collapse of 2014. There was not even passing acknowledgement of anything having gone wrong. The voters had erred, not the dynasty.

Congress lost space not only to BJP. Its present allies were equally happy to add fresh territory to their zemindaris. Democracy does not hand out prizes for sentiment. All opposition leaders know this. Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad have no problem while paying their respects to Sonia Gandhi in Delhi because they have marginalised Congress on their turf, Bihar. Lalu Prasad learnt a pungent lesson in the last Assembly election. If his party had not left over 70 seats to Congress, it might have won the election. He and Nitish Kumar will not repeat such a mistake. Congress has been in full-scale retreat from the Northeast, Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Delhi, Punjab, Gujarat, Odisha, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. It is struggling for a corner in Maharashtra. Rajasthan joins the wreckage.

Sonia Gandhi has not got the message. Her power, as is the case for all leaders in any democracy, is co-related to her ability to get votes, not simply to keep a diminishing party together. When regional leaders bring votes, they expect commensurate rewards, as Gehlot did. Congress remains a force in Haryana because of the dominating presence of Bhupinder Hooda. If his leadership is undercut, Congress will suffer grievously.

The most recent threat is from Arvind Kejriwal who knows that his growth opportunity lies in Congress displacement. He cannot rationally believe that he will win the coming Gujarat elections, but he will have taken a long stride forward in national calculations if the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) becomes the second force in the state.

Congress has become a puzzled jigsaw rather than a jigsaw puzzle, a combination of small cardboard pieces that no longer add up to a coherent picture.

The Rajasthan government has imploded, and the state’s governor would be well within his rights to dissolve the assembly and order fresh elections. Gehlot may have achieved more than he expected. According to the fluid and constantly wavering grapevine, Congress veteran Kamal Nath has also conveyed that he would rather be a potential chief minister in Bhopal than a signaturist in Delhi

In 1929, Mahatma Gandhi elevated 40-year-old Jawaharlal Nehru to the post of Congress president, setting in motion a chain of events that continues to influence Indian politics more than nine decades later. In the earlier era, a president was elected for just one year without any guarantee that he or she would remain an office-bearer under the subsequent president. But even a Mahatma had to persuade the party to accept his nominee. His principal argument in 1929 was that Congress needed younger blood for the battles ahead. He wrote that he looked like “a back number in their company” compared to them, adding quickly, “Not that I believe myself to be a back number”. Indeed, Gandhi would prove in 1930 that he was at the forefront of radical strategic thinking.

Gandhi gave a clear warning in response to expressed doubts about the incoming president’s suspect temperament. He wrote: “Lastly a President of the Congress is not an autocrat. He is a representative working under a well-defined constitution and well-known traditions. He can no more impose his views on the people than the English King.”

That was the Congress that was.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba