Clash of Ideals

NO FORCE ON earth is supposed to be able to stop an idea whose time has come. In 1991, a market economy for India was hailed as one, and to such euphoria that the poetic had turned tectonic by the end of that year's Budget speech: literally so, in my case, as a surge of stock traders at Jeejeebhoy Towers knocked me off a stairway perch to float along for a few moments on another crowdswell below. It was surreal. Today, as the country's target to fix the fisc gets kicked further down the calendar to 2021, the very idea of a time for that idea having come has begun to feel even more loopy. Had it? Has it passed? Climaxed prematurely? Gone into a warp? Has the State crept right back, set to loom over the Market again?

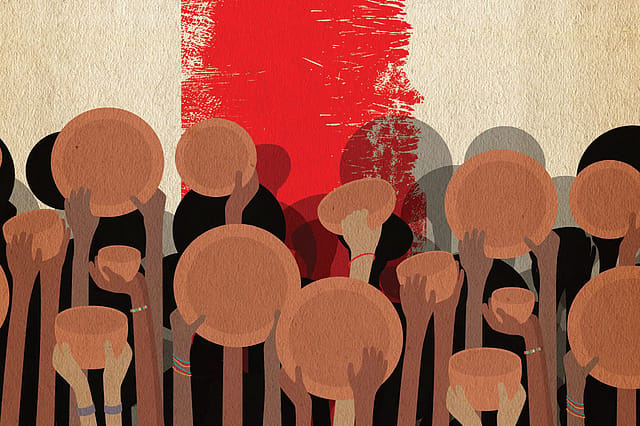

Clarity, like reliable data, is devilishly scarce. What calls for clarifying at this juncture, however, is that the original aim of India's reform agenda was not to enrich the rich, but expand the economy. For everyone. And for this, the country had to reduce central control, grant private players a larger share of resources to generate value—and jobs—in a way observed to work best: in open competition with one another. On global evidence, capital was found to enlarge an economy faster if it was allocated by a free market with millions jostling to converge diverse interests on their own, rather than by a bully state trying to guess what the voiceless value.

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

India has been admirably dynamic as an economy since it opened up, but also arguably less equitable in how its spoils are shared. While this has necessitated the adoption of welfare measures for those left out of the festivities, the overall policy trend seems to have defied almost every shift in power at the top. Consider the past five years. Easier entry to a field of business, for instance, needed to be complemented with the prospect of an orderly exit (and re-allotment of assets); this was partly addressed by a recently enacted bankruptcy law. Indirect taxes were crying out to be unified and simplified; even if the latter is left largely undone, legislation that enables as much has finally been passed. Above all, to achieve the sort of economic stability that would set the stage for both currency credibility and cheap credit over an extended period, the Centre had to ensure it would always earn enough money to cover all but a sliver of its expenses, even as the country's monetary authority kept a tight lid on inflation by letting only as much cash go around the economy as required. Armed with an explicit mandate to cap price levels, Reserve Bank freedom was crucial to this. Yet, it also called for fixing the fisc as top priority, the fulcrum on which the exercise would tilt. Delhi has duly displayed its dedication to the cause, but, alas, appears to have grown dithery over the past two years or so. What marks one phase apart from the other is the regime's cash evacuation of late 2016. So distinct has it been that it's hard to tell if the swerve off its fiscal 'glide path' is only a reflexive response to distress signals from farther afield or a decisive reversal of policy. The country's last blowout on this score was to prove so sticky that plenty went haywire. Relatively depressed private demand for investment funds since then could mean that a Central splurge on handouts doesn't throw prices out of whack this time around. Also, if tax revenues do somehow boom, as the Centre expects, then nothing much need go awry. All in all, the Market is vulnerable to the State, but not a victim of its excesses—yet.

What's more worthy of worry is why a liberalised economy has failed so many. Over a billion are 'Economically Weaker'. That the farm sector has not been freed of shackles is one answer; that Demonetisation was too hairy a shock is another (if way too short-termist). But perhaps the country needs to consider what some have gone hoarse arguing: that unless India flattens an age-old social hierarchy, a market economy will not be able to assure everyone a fair share.

In sum, a 'mixed economy', as once envisioned, may well be the country's most optimal choice.

The tricky question is what 'mix' would do the least lousy job of ensuring everyone's well being. And here, India's experience of governance since 1947 suggests that while the Gandhian mantra of serving the poorest of the poor needs to be accorded more than lip service, India ought to minimise arbitrary interventions of any kind in the Market, no matter how idealistic the intent. More minds tend to maximise a country's potential far better than a few.

To that end, there is still a long way to go.