Among the Believers

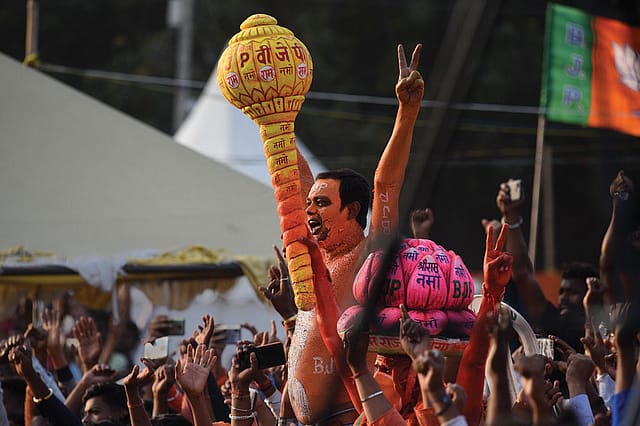

MAY 2ND COULD PROVE TO BE A transformative day for West Bengal. My extensive travels across the state, whereby I visited all of its 294 Assembly constituencies, indicate that a political and cultural shift is underway. This expected change and its implications are debated passionately but to understand why it is likely to occur, we have to explore the unique political history of Bengal.

For the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), West Bengal is not just another state it wants to rule. It is, instead, a rather emotional and ideological project that had provided the party two of its icons: Swami Vivekananda and Syama Prasad Mookerjee. The failure to entrench Hindutva as Bengal's dominant discourse after Independence has been a matter of regret more for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) than for BJP. RSS had moved into the state quite early, engaging with the refugee problem, a plank it had subsequently lost to Congress and the Left.

This failure in Bengal had led to the creation of a political myth around a twofold exceptionalism: that of Bengal and of Bengalis. It was argued that Bengal and Bengalis possessed a different worldview that did not sync with that of the rest of India. In reality, while Bengal had kept BJP at arm's length, Bengalis tended to embrace the saffron narrative enthusiastically in other states. For example, the Bengali-dominated Barak Valley in Assam had begun rewarding BJP in the early 1990s when the party achieved an emphatic victory there in the backdrop of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. By 2018, BJP had added yet another Bengali-dominated state in the Northeast, Tripura, to its electoral kitty with a big majority. A year later, in the 2019 General Election, with 18 Lok Sabha seats and about 40 per cent of the vote in West Bengal, BJP had breached the last wall of Bengali exceptionalism.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The 2021 Assembly election is, thus, about one critical question: with Bengali exceptionalism blown apart, will the Bengal exceptionalism—which has made its socio-cultural mosaic distinct from the political wave of Hindutva—continue to hold?

The expected shift on May 2nd—signifying the end of the Bengal exceptionalism—evident from my travels in the state as well as from several ground reports, is, of course, a matter of contention. Avijit Pathak, a sociologist at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, has called it, albeit with a sense of anguish, the 'mainstreaming of Bengal'.

THE MAINSTREAMING of Bengal as a political project is linked to the eastward expansion of both BJP and its narrative. The party having scored electoral victories in states like Assam and Tripura, along with other Northeastern states, it has been asked whether Bengal could afford to remain aloof from the saffron wave. Until 2019, and even after the Lok Sabha elections, this debate has been engaged with from two contending perspectives—first, that of the Bhadralok (the traditional cultural elite) who constituted the idea of Bengal in their own image and had hitherto succeeded in projecting it as Bengal's only reality; and second, the subdued story of the Bengal that lies outside the cultural core of Kolkata in general and the marginalised, or subaltern, sections like Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in particular.

While the elites privilege their exceptionalism, the second category is rooted in its everyday experience of precarity and political repression. So, by getting on the aspirational plank, these people exhibit an intense desire for political change. To the Bhadralok, Bengal's exceptionalism is a continuation of their privilege that they wish to guard zealously. But to the others, mainstreaming of Bengal is an instrument of their cultural assertion and aspiration. In this battle of narratives and contested claims about the authentic and the spurious, issues like the roots of anti-incumbency and Hindutva, the chanting of "Joi Shri Ram", the pitch of outsider vs insider, welfare schemes versus aspirational youth, among other things, need to be analysed from the vantage point of a looser binary—the anxiety of the Bhadralok pitted against the assertion of the marginalised masses.

POLLSTERS AND ANALYSTS have been trying to decide which—anti-incumbency or Hindutva—is responsible for the growth of BJP in Bengal since the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. While the near-unanimous response would be to attribute BJP's rise to a combination of both factors, an informed analysis requires marking a hierarchy between the two. Journalists like Snigdhendu Bhattacharya argue that had it not been for the decadal investment of RSS and its affiliate organisations, the current anti-incumbency would not have created a positive momentum for BJP in Bengal. A section of local intellectuals even goes to the extent of seeing Hindutva and issues like the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and Citizenship (Amendment) Act, or CAA, as the prime mover behind BJP's emergence as the main challenger to the incumbent state government.

However, based on my fieldwork, it could be reasonably inferred that seeing Hindutva as the prime factor—or the starting point—for BJP's growth does not hold. First, BJP outside Kolkata is not only weak in terms of organisational presence but also lacks local leadership profiles in most of the Assembly constituencies. Second, had the organisational investment by RSS across the state been accountable for the shift, BJP would not have had to find local candidates by inducting people from the Trinamool Congress (TMC), which has been a big problem for the party. Rather, this signifies something different—that the real reason for BJP's rise in Bengal does not lie in Hindutva.

To use the cake as a model to deduce the beginning of BJP's rise, it seems that more than Hindutva, it is the level of anti-incumbency against TMC that is responsible for creating a space for BJP. Anti-incumbency in Bengal is not normal as we saw in a state like Bihar in 2020. It is instead characterised by fear of, and by extension hate against, the ruling party. Under TMC, the nature and scale of corruption as well as physical assaults on political adversaries allegedly underwent a sort of paradigm shift. Unlike under the Left Front, corruption has grown manifold but, at the same time, it has been monopolised at the local level. Revealing stories paint a picture in which only TMC leaders or their representatives could participate in the parallel economy. Thus, corruption in Bengal was the result not of any normative outrage among the masses but of the exclusion of multiple stakeholders from its benefits. This could explain why the 2016 Assembly election proved to be a spectacular success for TMC despite scams like Saradha and Narada being raised strongly by the combined forces of Congress and the Left. Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee's popularity was intact on account of largescale welfare outreach which provided people with tangible benefits. Hence, the alleged corruption proved to be a non-issue electorally in 2016.

Nevertheless, an overwhelming number of respondents pointed out that since the beginning of its second term in power, on the back its electoral success, TMC got blinded by hubris. This led to the unleashing of a reign of terror against its political rivals as well as a plunder of public resources. This, in turn, triggered a largescale alienation of people from the ruling party. The pent-up anger of the masses kept building till the political blunder committed by the incumbent in the 2018 panchayat polls. The systematic violence during the panchayat elections proved to be a watershed.

The template of physical assault on non-TMC leaders, cadres and ordinary people was such that TMC won more than a third of panchayat seats uncontested. Across the state, people narrated stories of Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPM) cadres and supporters being the main victims along with Congress and BJP supporters. Even septuagenarian Basudeb Acharia, a nine-time Lok Sabha member from Purulia, was attacked, allegedly by TMC cadres, when he went to protest against the prevention of CPM candidates from filing their nominations. As per the popular narrative, the police remained mute spectators or became active collaborators. While Bengal has always had a police closely tied to the ruling party since the days Siddhartha Shankar Ray, under TMC, it suffered a big loss of face and earned the pejorative title of being the 'gunda bahini' of TMC. It is in this context that one should place the demand from people that the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) be made central to the security of the electoral process in the 2021 election as the state police seem to have lost their credibility.

Thus, having battered the opposition and humiliated CPM leaders, TMC was oblivious to the fact that in its zeal to finish off the Left as a credible alternative, the party was enabling its own nemesis—BJP.

A comparative study of the 2016 Assembly election data with Assembly constituency-wise breakup of the 2019 Lok Sabha data reveals the shift of the Left's support base to BJP. Led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Home Minister Amit Shah, who took a serious interest in the state before the 2019 General Election, BJP captured the imagination of the anti-TMC social base even as CPM and Congress became weaker forces, unable to come to the support of their own people. This tectonic political shift was visible in the last Lok Sabha elections.

THE STORY ON the ground in Bengal demonstrates that, to return to the cake analogy, the base of the political shift in favour of BJP is anti-incumbency. Hindutva is the layering on top of the base. While religiosity is a perennial phenomenon in Bengal—people often remark that the state celebrates 13 mega religious festivals in the 12 months of a year ('Baro Mashe Tero Parbon')—the political interplay of religious events never came under the analytical gaze. The usual refrain, peddled mostly by the Bhadralok, had been that Bengal's religiosity primarily pertained to social occasions and, therefore, its festivals were distinct from the religiosity displayed in neighbouring states, that is, the Hindi heartland where religion and politics readily overlapped.

This claim may be true of a place like Kolkata. But, for the rest of Bengal, the equation of ubiquitous religiosity and politics is more complex. This complexity has acquired significance in light of two separate but connected issues. First, the interplay of corruption and political repression has created a deep resentment against TMC, leading to a situation of 'TMC versus the rest of the masses', including a big section of lower-caste Hindus. Second, the perception that the ruling party is catering more to minority interests—owing to policy measures like allowances for imams and muezzins that ended up compounding the resentment among Bengali Hindus, particularly SCs and STs. BJP's emergence as the only credible alternative to TMC fused these two issues. Thus, anti-incumbency tactically embraced Hindutva without privileging it, as has been argued by many analysts. However, there is always fertile soil for a tactical move being internalised and constituting the core of the socio-cultural and political outlook of the people involved. The question whether, in due course, the tactical move of Hindutva by Bengali Hindus will morph into an ideological conviction is yet to be answered. At the moment, the desire for change is largely the outcome of a strong sense of anti-incumbency, with Hindutva providing it with a binding structure that can be mobilised.

ANOTHER ISSUE THAT saw interventions from intellectuals like Amartya Sen, political parties, social activists and journalists is the genesis and character of the chant "Joi Shri Ram". A debate has raged on what this chant signifies.

The chant was heard on three occasions: during the 2018 communal riots on Ramnavami in Asansol; chanting by people as Mamata Banerjee's motorcade passed through Chandrakona in West Midnapore and Bhatpara in North 24 Parganas in May 2019; and, on January 23rd this year, when the slogan was raised in the presence of Modi and Banerjee in Kolkata during the celebrations to mark Subhas Chandra Bose's birth anniversary.

The immediate response from the Bhadralok was a twofold assertion: one, Ram has never been central to the popular religious imagination of Bengal. Thus, the provocative sloganeering must have been BJP's handiwork. Two, those chanting must have been primarily Hindi-speaking migrants settled in Bengal. Many of these claims employed the 'No True Scotsman' fallacy by arguing that no true Bengali would chant a religious slogan that owes its origin to the Hindi heartland. These claims are informed by Bengal and Bengali exceptionalism.

In my interactions with respondents across the state—from northern Bengal to Jungle Mahal and from Nadia to South 24 Parganas—a different reality surfaced. First, while Hindi-speaking people have turned to BJP, an overwhelming majority of people who are chanting "Joi Shri Ram" happen to be Bengali Hindus even in areas that do not share a border with Bihar or Jharkhand. While in many places respondents admitted that chanting the slogan began as a political stance against TMC with the intent to tease, it soon became a marker of political identification for those who wanted to signal their political shift. On being asked why they did not opt for other religious slogans, the answer was the assertion that Ram is as integral to Bengal as to the rest of India. At Bishnupur in Bankura, the claim that Ram was a part of everyday life was substantiated with reference to how the Ramayana is inscribed even on the famous Baluchari silk sarees from the district. In North 24 Parganas, a group of OBCs (Gwala Ghosh) and SCs like Matuas defended the centrality of Ram. In a district like Purulia, where the Mahato-Kurmi caste dominates politics, respondents from the Kumbhakar (potter) caste, who aspire to compete with the Mahato-Kurmi, invoked their affinity to Ram to emphasise their greater affinity to BJP. This mismatch between the narrative on the ground and that of the intellectuals brings us to another contention about the nature of BJP in Bengal.

WITH THE ELECTORAL process in full swing, TMC raised the pitch by declaring BJP a party of the bohiragoto (outsiders) attempting to destroy the cultural contours of Bengal. Vandalising of the Vidyasagar bust during the Lok Sabha elections and the perception that BJP supporters were responsible are believed to have worked in favour of TMC in the Greater Kolkata area that had its polls after the incident.

Expecting an electoral dividend, TMC has been campaigning aggressively on this plank. However, it does not seem to resonate with the masses, particularly with lower-caste Hindus and rural peasant castes like Mahishyas, Aguris, Gwala Ghosh, etcetera, for whom the incumbent regime signifies corruption, repression and minority appeasement.

In the age of populism, there is a new trend whereby, depending on parties or leaders, people buy or reject their political narratives. In the past, the perception that Modi meant well and his intentions were right convinced many to set aside their individual sufferings and come out in support of a policy like demonetisation. On the other hand, there are many examples of unpopular regimes being ousted despite their well-meaning policies and initiatives before elections. A majority of people on the ground have made up their mind to vote for change. In that situation, the attempt to paint the only credible alternative in the state—BJP—as a party of outsiders could end up further provoking the electorate for whom it is the party of emancipation and who wish to see an end to the current regime.

ANOTHER PUZZLE that divides analysts and clouds the undercurrent against TMC happens to be the claim that since Bengal has a larger rural population, including a substantial presence of poor SCs and STs, Banerjee would have an edge because of welfare schemes that take care of different sections of the population for their entire lives. This argument may sound persuasive but it misses the reality by half. While the claim of welfare schemes is true, the fact is qualified by the problem of alleged largescale corruption in the disbursal of every scheme. Further, the partisan political culture has ensured that inclusion of beneficiaries is also determined along political lines. One can imagine the extent of partisanship from two extreme examples from two different regions. In Cooch Bihar district in northern Bengal, known for outward migration, there were big complaints of corruption and exclusion in MGNREGA during the lockdown. In southern Bengal, in areas like East Midnapore, Howrah, parts of Hooghly, North and South 24 Parganas, as well as Kolkata, where super cyclone Amphan destroyed lives and livelihoods, the alleged level of corruption was so high that people started referring to the plunder of resources meant for victims as Amphan Durniti (Amphan corruption). Hence, the logic of the centrality of welfare schemes and their translation into votes for TMC sounds fallacious on two counts. First, elections are never a logic-driven phenomenon and, second, the ground reality and sentiment on the primacy of corruption are deliberately underplayed.

A third factor that has turned the tide against TMC is the emergence of the aspirational youth who has always been the agent of change, be it in 1977 when the Left came to power ousting Congress or in 2011 when TMC defeated the Left after its 34-year-long rule. Young people in general and subaltern youths in particular emerged as a vocal category that privileged jobs over welfare schemes. It is indisputable that the TMC government's record in providing jobs has been very poor compared to the Left Front government's. Hence, the party has lost the youth and millennials of all classes. Against this backdrop, BJP has emerged as a package signifying aspiration for the youth, emancipation for political victims, development in general and Hindutva as far as the political psychology of the masses is concerned—of those who share the idea that Bengal needs a Hindu renaissance.

The cultural elite may privilege ideology and remain in denial about the undercurrent in favour of BJP but the larger masses of Bengal have placed their everyday experience of repression and precarity above ideology. BJP is the default beneficiary of this, its organisational weaknesses notwithstanding. Bengal seems set to be swayed by a saffron wave.