A Passage to India

Feeling freer than ever on a beach in Tamil Nadu

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

|

11 Aug, 2023

|

11 Aug, 2023

/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/PassagetoIndia1.jpg)

A Claude Monet painting of the Pourville beach, 1882

August 1982, Pensacola, Florida

I ’M NOT YET 17. I’ve just landed at New Orleans airport. I’d been told it was going to be so hot I would barely be able to breathe outdoors, compared with the icy and damp Northern Italian valley I spent my winters in, at the feet of the Dolomites. But I feel ok. It’s not as hot as expected. It’s really bearable.

As I exit the airport, when the automatic glass doors suddenly open, I realise there’s full air conditioning blowing through the airport. The wave of real humidity hitting me in the parking lot, as I board a station-wagon for a four-hour drive east, is something I’d never felt before. And yet, this muggy breeze taking my breath away feels like freedom to me.

I’m escaping from oppression. My father’s Prussian upbringing, my high-school’s uninspiring teachers, the distant province of southern Europe where everything seems to arrive too late compared to the rest of the Western world—the enticing reality brought to me by television, movies, on the radio, in books, magazines and newspapers.

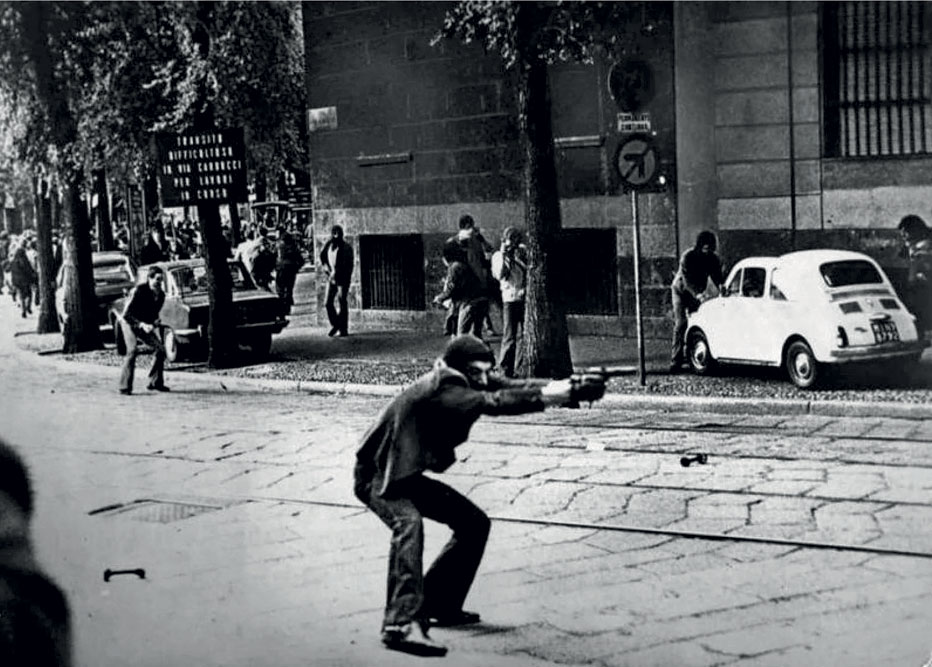

Italy is exiting the Years of Lead, a decade-long streak of terroristic attacks—from bombs in train stations, to kneecapping journalists and police officers; from kidnapping children of rich families to finance the communist revolution, to executing the president of the leading political party. I take in the news leafing through the daily paper, turning the knob to watch the evening news on a black-and-white TV. It feels like gulping a spoon of poison at a time. We’re crushed in a Cold War, near the Iron Curtain which actually begins in non-aligned Yugoslavia, a three-hour drive from my town. With my peers we chat about our fear of atomic Armageddon. What would we do in the radioactive fallout? I don’t envision any future for me, in this complex nepotistic society where there’s no innovation, where the past represented by the long faces of old politicians is suffocating my future and my dreams. I don’t have access to a road leading anywhere. I am trapped.

Volere l’America is an Italian expression which means “to want America”, craving something impossible. I want the impossible. When I see a poster advertising a year in the US through the Educational Foundation for Foreign Students, I send in the form. My grandfather offers to foot the bill for the fee. A family in Florida picks my application, they like my essay where I explain why I want to live in the States for a year with a group of strangers. That’s why at 16 I say goodbye to all my friends, to my first girlfriend who dumped me for an older and more handsome boy, to my family, my ski-racing and basketball teams. I must leave behind my skateboard which won’t fit in my luggage, get a haircut, say goodbye to all the novels that made me crave something beyond this valley, pack my bag, put on a white Polo shirt, and board an airplane for my first transatlantic flight which I’ll spend with my forehead glued to the window, lost in dreams among the clouds. There’s a picture of me outside the Milan Malpensa airport, on my last day in Italy. I’m radiant. Smelling the freedom ahead. Hiding well the mild fear of leaving everything and everyone behind, infused by the euphoria of novelty.

In Florida, I start high school as a senior. I have the freedom to work in the school paper, to write editorials, and news stories, my dream of being a writer already finding a first door that was closed to me where I came from. When I learn to get up on that surfboard on the Gulf of Mexico, I get slammed down right away, no freedom there, I’m not good enough. But I have the freedom to try out for the football team as I can kick the ball from the 40-yard line, barefoot. And the freedom to quit right away, as I want to pursue my studies.

I’m reminded that I am a resident alien. I have a white T-shirt with the orange silhouette of the State of Florida and that word written across it: “Alien”. It is perhaps here, in Pensacola, near Alabama, that I first sense the tingling and exciting sensation that being disconnected from the local reality can give you. You are a visitor. You are a traveller. You are a nomad coming through, as I’ll always be from now on. You are free.

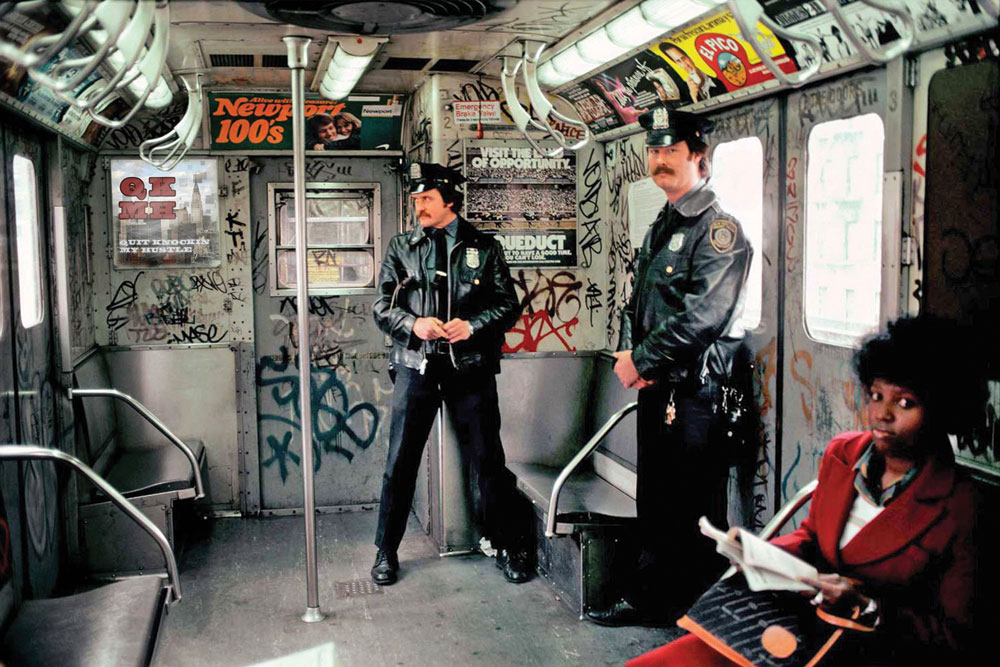

September 1987, New York

I FINISH HIGH SCHOOL in Pensacola. I get a Bachelor’s degree in Washington DC. I work as a summer intern at the Associated Press in Rome, landing a job in New York City at Fortune magazine. On another transatlantic flight from Italy to America, I dream of a new chapter in life, and the extra freedom it could bring in pursuing the dream of making a living with writing and having an adventurous life along with it.

New York in the mid-1980s, a boy barely over 20, heading to work for Fortune magazine… The Monday I show up at the Time-Life building to see where my desk was, the Wall Street stock market crashes. As a few brokers leap out of their skyscraper windows, I’m out of a job the day I am supposed to start it. But I am in New York. The freest city in the freest part of the free world. I find a bed in a windowless room in Greenwich Village. And look for work as I must support myself.

After many failed attempts, I get a job at a newspaper. Freedom means coming home from work, going for a pre-dinner nap, grabbing a bite, and heading out to enjoy the night, crossing paths with celebrities, thugs, other dreamy young people like me dancing to R&B, soul, funk, hip hop and dance music which was turning churches and banks into party palaces. Freedom is staying out late, getting up early and going to work again. It’s not only the hedonistic pursuit of pleasure, but the possibility of learning from artists, filmmakers, writers, poets, designers what it means to interpret the world.

While I believe I’m free, I am also hostage to my own dreams, and the path presented to me in order to pursue it. I work hard, not all that free, caught in the trap of New York, which makes all of us feel like we can never leave it, as we will never find anything as good as this, ever, anywhere else in the world. I think I have freedom, but I’ve built the beautiful golden bars of a mental prison, unable to escape, caught in the net of the excitement.

May 1997, Mexico City

AFTER NEW YORK, I go back to Rome at the newspaper headquarters, working at the foreign desk. The editor-in-chief sends me to cover Latin America. I got a free-lance contract that allows me to work with more independence, producing documentaries as well as articles, administering my time without the mediation of paid but limited holidays.

Freedom is being able to carve a professional path to the life I want. It is the liberty to travel to new places, to hike in the Andes with the last preachers of Liberation Theology, to feel the excitement of constant novelties, to be drenched in the passionate idealism permeating the whole of Latin America, shaped like a heart.

I find myself reporting for the newspaper at the funeral of Che Guevara in Santa Clara, Cuba. Fidel Castro speaks for four hours under the scorching sun. I hop around the continent interviewing Zapatista rebels in the jungles of Chiapas, in Mexico, meeting presidents in their guarded palaces in Argentina, Chile, and Peru, skirting bandidos on the Guatemalan border, interviewing Maoist guerrillas in the Colombian forest, flying in a helicopter over coca plantations in the Andes…

Freedom means not staying in the same place for more than two weeks in a row, to pursue a thirst for experiences, at 31. I feel freedom means a chance to make mistakes. And I make them.

October 2008, Mysore

I ’M 42 YEARS OLD, landing in India for the first time. More than freedom, I seek serenity. Things got complicated with work, with life, with broken hopes. Time for a reboot. Like many other wounded souls who reach India from Australia, Canada, America, and Europe, I land in Bangalore thinking India will change me. The intensity and vivacity of daily existence is exhilarating. I learn yoga Ashtanga with Sri Pattabi Jois in Mysore, go through a regenerating panchakarma in Kerala, walk barefoot around the holy mountain of Arunachala while chanting the mantra to Shiva.

As I crawl on the floor through the narrow passages between two columns of the Idukku Pillaiyar shrine, along the pradakshina in Tiruvannamalai, I ask Ganesh to simply grant me some happiness, nothing else.

Freedom, in the infamous mid-life crisis phase of life, means being able to transform, to change, to reboot. It begins to feel like you are the jailor of your unhappiness.

Can’t tell if it’s all that oil and ayurvedic herbs, all the dawns spent sweating on a yoga mat doing asanas, Ganesh listening to my request, the deep and frequent meditations, but yes, I turn out to be that comical Western cliché of the gora who indeed is changed by India. This transformation, the more patient, wiser me, feels freer because it is less affected by the excessive thought surrounding reality. This freer me seems to be able to organise life better. It has found a freedom that has nothing to do with wealth; on the contrary. The freedom to administer what is already there in a different way. Freedom is a change of perspective.

Today, Paramankeni, Tamil Nadu

THE BOY WHO left home at 16 for a coastal town in northern Florida is on a beach again. And no longer a boy, judging from that salt-and-pepper hair and white beard.

I feel freer than ever. I experience a morphed sense of time in this isolated life on the beach: days run faster, weeks pass by slower, months vaporise by seeming endless and quick at the same time. The routine, the self-imposed jail of discipline that I learned better than ever in India, generates freedom.

The sky and the sea are alive and vivid, but they can also become the blank slate on which to let my imagination and analysis of reality work at their best. The rhythm of the daily walks gives pace to thoughts, while pumping some blood to the brain. The iodine of the sea cleanses all that needs to go. Freedom on the eve of 60 feels like this. Not having to prove much, trying to be, learning that when enough aches add up you can’t complain about them any longer, as it doesn’t help. Freedom is time to do what you want. And knowing what to do with it. As the ultimate freedom awaits.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-OpenMinds2025.jpg)

More Columns

Puri Marks Sixth Major Stampede of The Year Open

Under the sunlit skies, in the city of Copernicus Sabin Iqbal

EC uploads Bihar’s 2003 electoral roll to ease document submission Open