A Conservative Rooted in the Present

His nationalism was not paranoid even as his position blended the Sangh’s cultural pride with the demands of modernity

/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Conservative1.jpg)

February 2018: Arun Jaitley in his office, New Delhi, after presenting the Union Budget for 2018-2019 (Photo: Rohit Chawla)

ARUN JAITLEY’S POLITICAL temperament was cast in the most turbulent of times in independent India—the fiery 1970s. The era, coming after the relative calm of the 1960s, transformed the country into a crucible of angry agitations and stormy student movements railing against the Government of Indira Gandhi.

On the one hand, there were celebrations for the 25th year of Independence. But on the other, lurked the shadow of violent flux. These era-defining agitations culminated in the overthrow of the Congress regime, with the constabulary in Uttar Pradesh threatening revolt and students across college campuses placing themselves at the centre of the protests.

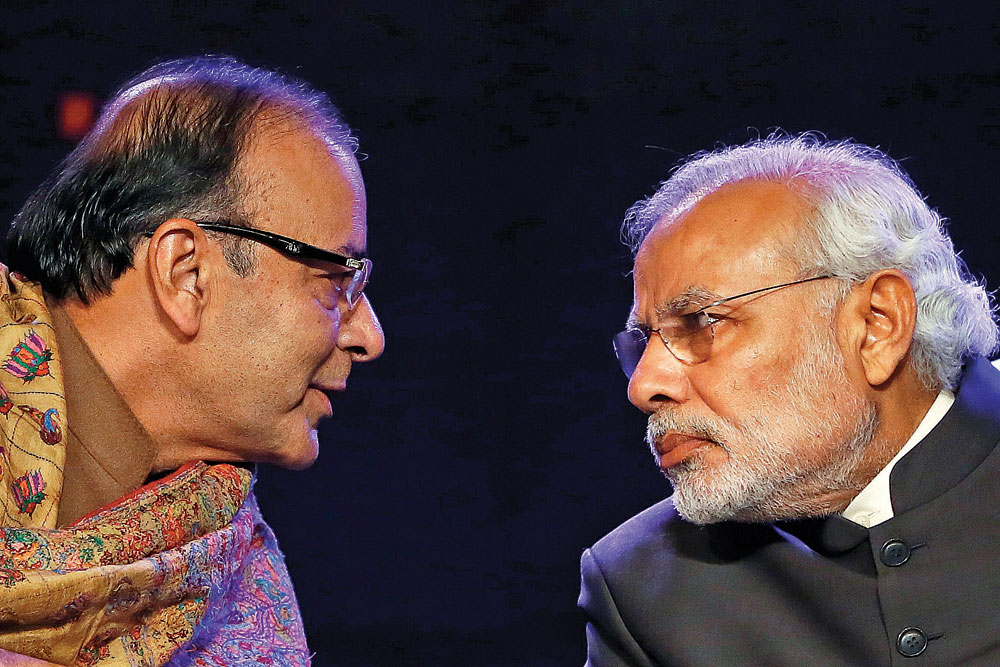

Jaitley—who decades later, in mid-2014, positioned himself at the core of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s powerful brains trust (the other being Amit Shah)—was a callow, 22-year-old law student at Delhi University in the 1970s. Months, even years, before Emergency was declared in 1975, many of India’s latter-day key leaders, including the likes of Jaitley himself, Nitish Kumar, Ram Vilas Paswan, Sharad Yadav and Lalu Prasad, were the fulcrum of campus protests that spread from Ahmedabad to Patna and to other towns that were being brought to their knees. This was the run-up to Emergency. The agitations kept India on the boil. In end-1973, a rocky student protest over canteen charges at the LD College of Engineering in Ahmedabad rose to a crescendo, leading to police storming the campus. The blowback which followed swiftly seared Ahmedabad city, with multiple incidents of rasta roko, bandhs, arson and looting aimed at the state government. Ahmedabad was burning and the Army was called in to control the violent protestors.

But the protests had spread to other towns like Patna, already a hotbed of political activism. The ABVP and other likeminded people gheraoed the state Assembly and held largescale street protests. As these peaked, socialist leader and freedom fighter Jayaprakash Narayan was pulled into the movement by students as their torch-bearer. JP, once a comrade of Nehru, called for Sampoorna Kranti or Total Revolution against the elected Government of Indira Gandhi— which stood accused of making institutions toothless and a mockery of democratic norms and processes even within the Congress party—to wrest absolute power. The JP Movement, as it came to be known, was fuelled mainly by the RSS, the Jana Sangh, Socialists and anti-Indira Congress leaders. In the thick of this turbulence of Yuvashakti, as JP dubbed it, Jaitley, who was a very prominent ABVP activist and later president of the Delhi University Students’ Union, travelled first to Ahmedabad and then to Patna to stoke the JP Movement into a conflagration against the elected governments in both states. His hard work and unstinting political activism received recognition when he was promoted from Delhi University’s student union president to convenor of the Sangharsh Samiti, an umbrella for all the protesting groups nationwide in 1974.

Early the next year, then Minister of Railways LN Mishra was killed in a bomb blast in Bihar. Later that year, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who headed a two-thirds majority in Parliament, was sought to be barred by an Allahabad High Court judge from contesting elections for six years, based on violations of election rules. The Supreme Court granted her a stay. Arun Jaitley was at the centre of the student agitations called for by JP to swell the ranks at a big rally planned in the capital which aimed at forcing Indira Gandhi to resign by gheraoing her house. JP also called upon the Army and the state police to disobey Government orders to quell the protests.

It was the student leader tempered by fire in the turbulent 1970s who came up with the plan to invite all of the neighbouring countries to Narendra Modi’s oath-taking ceremony

Around midnight of June 25th, 1975, Indira Gandhi declared Emergency that restricted civil rights, the media and communication, and suspended political activity. She also began jailing all or most of her opponents in politics as well as those among artists and public intellectuals.

The morning after the proclamation of Emergency, June 26th, Jaitley received news that he was to be arrested and fled from his home while his father, also a lawyer, kept the police engaged in conversation. Surfacing at Delhi University, Jaitley gathered a group of people and burnt an effigy of Indira Gandhi, making him, in his own words, the “first satyagrahi” against Emergency since it was the only protest staged that day. Jaitley was later arrested under preventive detention and was in custody for 19 months, from 1975 to 1977.

Years later, on October 11th, 2015, in his speech on the occasion of JP’s 113th birth anniversary, Prime Minister Narendra Modi referred to the “new political generation” that was born during Emergency and the JP Movement, maintaining that Indian democracy had been strengthened by them.

IN THE DAYS AFTER the overthrow of Indira Gandhi as Prime Minister, Jaitley was recognised prominently for his leadership qualities during the JP andolan and the anti-Emergency movement. His name was proposed for the 10-member National Executive of the newly formed Janata Party, alongside those of stalwarts like AB Vajpayee, LK Advani, Nanaji Deshmukh. However, he resigned from the panel the very next day after the ABVP showed its displeasure at its activist joining a political party.

For years afterwards, Jaitley chose to be an ordinary activist and to work for the BJP which was formed in 1980. It was at the end of the 1980s, when VP Singh came to power, that Jaitley’s next big political opportunity came. Singh offered him the post of Additional Solicitor General. He accepted, diving almost from the word go into doing the paperwork for investigations into the Bofors deal—as well as the FERA (Foreign Exchange Regulation Act) case foisted on Singh and his son Ajeya.

From 1991—when Jaitley was made a National Executive committee member of the BJP, 11 years after its birth out of the Jana Sangh—till the 2019 General Election, every single political and economic resolution adopted by the party was either drafted or vetted by him. Jaitley used this time to focus on his already flourishing legal practice, showcasing his electric ability to grasp the most complex issues and the nub of the problem at hand. In the Hawala (Jain Diaries) case against his mentor LK Advani, he showed that the mere entry of one’s name in a diary could not be accepted as proof of one’s corrupt actions.

It was Jaitley, with his intellect and silver tongue, who coined memorable phrases and sound bites that aptly mirrored the environment, including policy paralysis

Maninder Singh, Supreme Court advocate and one of Jaitley’s juniors when he was fresh out of college, recalls being asked to prepare a brief in a preventive detention case which they won. Jaitley insisted on giving Singh the lion’s share of the fees earned. He also made it a habit to donate 10 per cent of the fees to the clerkage account which his juniors accessed years later to buy two-three bedroom houses closer to their office. “Nothing made him happier than knowing that one of us had moved closer to his own home in Kailash Colony,” Singh wrote in his tribute. Some of those mentored by him, who are today advocates at the apex court, testify to how he believed in burning the midnight oil to prepare for cases long before they were to come up in court, testing the strength of each argument through the pros and cons of a proposition. It was a gold standard that he inculcated in all his legal protégés.

Thereafter, Jaitley moved on speedily to become a minister in the Vajpayee Government and later, by dint of sheer intellect and hard work, to head key ministries and departments as varied and crucial as Law, Commerce and Industry, Information & Broadcasting, Defence and Finance. Jaitley later carried his irrepressible instinct to suss out, polish and nurture protégés into his years as a full-time politician, after he gave up legal practice. This was when he took the likes of Dharmendra Pradhan, Piyush Goyal and Nirmala Sitharaman under his wing to build the GenNext line of BJP leaders.

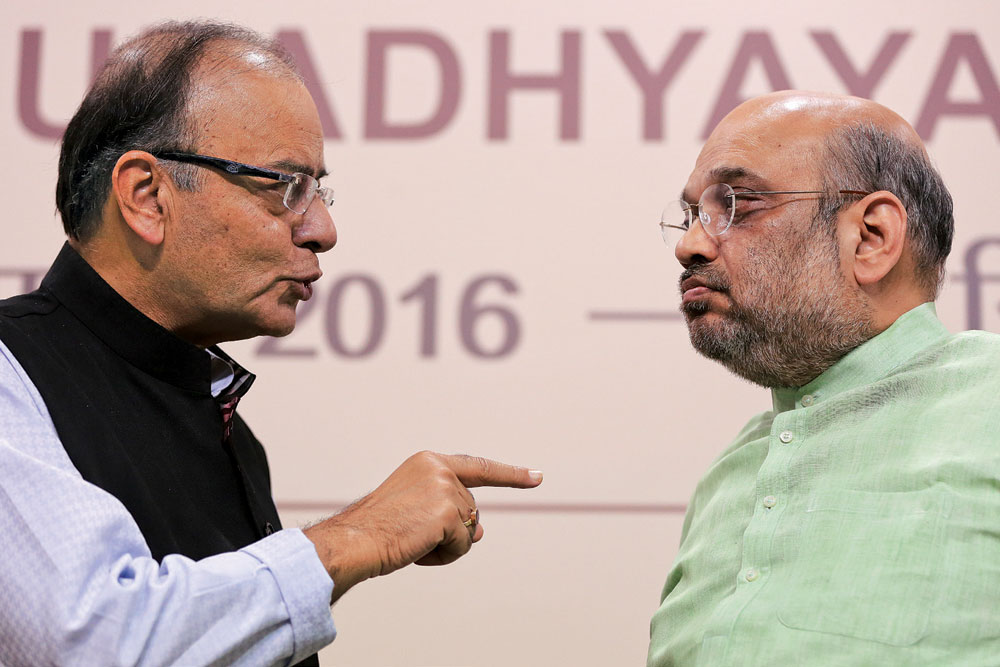

It came as a surprise to none when, after the massive mandate in May 2014, Modi’s brains trust had just two of the party’s ablest men, one with the sharpest intellect and policy perspectives besides excellent networking skills and an insider’s view into Delhi’s corridors of power, Jaitley, and the other a master electoral strategist and logistics man, Amit Shah. Both men went way back with Modi and had his total trust. Weeks before government formation, it was Jaitley who separated the grist from the chaff as potential ministers. He turned his two-storey house at Kailash colony into a war room of sorts for government fine-tuning and policy preambles. Those who saw themselves as probables and wound their way to 7 Race Course Road were quickly dismissed and had to queue up either at Gujarat House to meet the very matter-of-fact and brusque Shah or to meet the suave but equally firm Jaitley.

It was the student leader tempered by fire in the turbulent 1970s who came up with the plan to invite all of the neighbouring countries to Narendra Modi’s oath-taking ceremony, projecting his statesman-like qualities and firmly countering criticism that he was a parochial politician. It was Jaitley who helped the new Government navigate the labyrinths of Lutyens’ Delhi, ensuring a seat at every high table in its ecology—political, business and economic, and social. It was Jaitley who honed the contexts for a radical decision like demonetisation, for the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), for the banking and insolvency bill. It was Jaitley who contextualised and demystified these complex decisions for the media, within the framework of party ideology.

It was Jaitley, with his intellect and silver tongue, who coined memorable phrases and sound bites that aptly mirrored the environment, including policy paralysis and the actions of compulsive contrarians as well as of those behind issues like ‘Award Waapsi’. When the highly regarded Defence and Finance Minister of Modi 1.0 excused himself from an active role in Modi’s second term due to illness, it was Narendra Modi who felt the absence of his long-term friend and associate and his helping hand the most. “We met initially as associates in the BJP decades ago but over time, our association transformed into something far closer and we grew to trust each other implicitly,” Jaitley had said about Modi in an interview.

Jaitley, with his sharp eye for leadership qualities, was among the first to identify and hone in on Narendra Modi, then the Chief Minister of Gujarat, as the ablest candidate for the BJP’s prime ministerial nominee long before 2014. It was Jaitley who countered attempts by LK Advani, his erstwhile mentor, to derail Modi’s possible nomination as the party’s prime ministerial candidate. This close association between the two men was cast in stone after Modi’s nomination was sealed. And in May 2014, Jaitley was the first to call and congratulate Modi on his massive victory. Electoral history had been made. Although he himself had lost from Amritsar, it was clear that Jaitley would play a nodal role in Modi’s Government.

Two things defined Arun Jaitley aptly and consistently from his student days: food and food for thought, especially that with bite. His rapier-sharp intellect drilled through the hardest topics with ease while his cutlery would pirouette at the sight and aroma of good food and the scintillating conversations spinning around it. His incisive intellect revealed itself in the most cavalier interaction with him as did his interest in a smorgasbord of issues, from the sublime to the mundane, from the complicated to the simple. He made it his business to suss out the nooks and crannies, the gullies and nukkads of every issue that caught his imagination. From Mughal history to where the best serving of rogan josh could be found in Delhi to the fine points of the Bofors case, from the problems of NBFCs to a hitherto unpublished story about Sanjeev Kumar to Norman Mailer, JM Keynes and Milton Friedman, from the cricket World Cup that Kapil Dev won for India to how Lata Mangeshkar’s dulcet tones came to render that particular version of a famous 1960s Hindi movie song. He generously disbursed select insights from what he gleaned to an awed audience at the famed ‘courts’ he held, whether at a gathering of the media, of the legal fraternity, of chartered accountants, of industry associations or of fellow politicians and protégés.

Those he loved, family and friends, or closely interacted with, irrespective of class, colour and creed, vouch for the fact that Jaitley gave his relationships his all. But his sharp eye and ability to spot kindred spirits and young talent also did not allow him to brook the lazy and the languorous of mind and slovenly of spirit. And he did not bother to hide it. Whether they loved him or not, no one who had ever heard him or interacted with him, even briefly, could fail to be affected by his fascinating personality—burnished over the years by hard work and integrity so rare in a politician—which would certainly light up any corner of any room anywhere.

Maninder Singh narrates an instance of Jaitley’s impeccable integrity. Jaitley, he says, put an end to the practice of preparing bills in advance in the morning, even before the appearance in court of the advocate, declaring that “I must put an end to this now.” Singh writes: ‘Arun Jaitley was honest to the core, loyal to values both personal and political, astute in details and put people and their interest above his own personal during a long political career straddling from student politics to national one, rising to substantive positions within the government.’

Those with long associations with him recall times when he hitched a ride in a friend’s Fiat car part of the way home and then took a three-wheeler to Naraina, where he lived at the time. He never forgot those roots and days of relative simplicity and struggle even in later years when he helped his juniors move out of their minuscule houses into two-three bedroom homes, funded by the clerkage account from the fees earned.

It stands to reason that there were so many who claimed a personal relationship with Jaitley and were influenced by his worldview. The values he treasured that came to be so widely appreciated in his years as a full-time politician later were evident as far back as during his student days. India TV’s Rajat Sharma, whose close connect with Jaitley goes back 40 years to his college days at the Shri Ram College of Commerce (SRCC), when the latter was already in the first year of his law course, remembers how Jaitley was famous for his debating skills even in his student days and how he had an uncanny ability to grasp the crux of the matter and gain an in-depth knowledge, pertaining to any issue he touched upon.

Sharma, who broadcast a special tribute on his channel after Jaitley’s death, narrated how he had to collect small change in order to manage his fees at SRCC upon admission and how he ran short of a paltry sum of Rs 3 when he finally found himself at the head of the queue—and also, humiliatingly, at the receiving end of the berating staff collecting the fees. It was Jaitley who came over to help him with a loan of Rs 5, followed by desperately needed tea and empathy.

It was his love of food and forbidden sweets, apart from his cracking skills as a raconteur, which helped Jaitley build abiding associations across the political spectrum. When he was Leader of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha and later House manager, every senior worthy from the opposition ranks would troop in to his room to gorge on food brought in from his home.

IN THE 1980S, the most radical contribution of LK Advani, Arun Jaitley’s mentor, to the dominant political and cultural ecosystem of the day was the in-your-face defiance to create a significant niche for the BJP. His seminal act was that of discrediting the idea of ‘secularism’, seen as sacrosanct by a majority for decades. It was a political narrative that broke rudely from a moribund etymological and ideological past in order to ensure historical and cultural justice.

Jaitley and his peers not only strengthened and built further on the foundation laid by Advani, but in one key respect, Jaitley differed from Advani. The former BJP president did not succumb to the terms of engagement set by the Nehruvian elite, but somehow he still hankered after acceptability among the set he questioned and despised.

The second aspect became particularly noticeable towards the later part of his political life. Advani himself acknowledged that he would have to take a backseat in the Government compared to Vajpayee after playing a key role in the Ayodhya movement that culminated in the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6th, 1992, since he would not have the sort of widespread public acceptance that Vajpayee enjoyed. The Ayodhya movement, which Advani spearheaded with his rath yatras, directly rebelled against mainstream cultural and political views on the subject, centred on the idea of secularism.

HOWEVER, THIS APPARENT self-celebration of an open challenge to a cornerstone idea in the mainstream consciousness fell flat later on, when Advani, by now getting restive playing second fiddle to Vajpayee, suddenly changed his position on the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, hailing him on a visit to that country. In doing so, he was in fact backing the viewpoint of the self-proclaimed ‘secularists’ of India even while playing to the gallery in Islamabad. Standing at Jinnah’s tomb in 2005, Advani described him as ‘secular’ and an ‘ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’. Advani wrote in the register: ‘In his early years, Sarojini Naidu, a leading luminary of India’s freedom struggle, described Mr Jinnah as an ‘ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’. His address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947, is really a classic, a forceful espousal of a secular state in which, while every citizen would be free to practise his own religion, the state shall make no distinction between one citizen and another on grounds of faith. My respectful homage to this great man.’ With his volte face on the Jinnah issue, Advani found acceptance among the entrenched elite.

Jaitley was strikingly different from Advani on this issue since he refused to succumb to the pressure to acquire legitimacy from the elite by calibrating his own ideological standpoint. Jaitley was a known figure in the Lutyens’ system and at ease with the Nehruvian elite. In a peculiar way, he was an intrinsic part of the Lutyens’ set up, but in his own right and with his ideology intact.

Unsurprisingly, he felt little pressure, subtle or overt, that is usually brought to bear upon leaders to make them conform to the zeitgeist of Delhi. In the obituaries written for Jaitley, therefore, some maintained that he was the ‘right man in the wrong party’, a phrase the liberal elite also insisted on using to describe Vajpayee.

Jaitley never felt the need to be apologetic about his ideological perspective or to hanker after legitimacy. At the same time, he did not believe in unfurling a flag over ideological positions either with acquaintances who sported differing political views. He refused to venture into confrontation, disrupt his relationships and violate social bonds even with people who held diametrically opposite views. But this did not come at the expense of his belief in his own party’s ideology. One of the deceptive things about Jaitley, despite his seemingly cosmopolitan nature, was that he steadfastly held on to the core Hindutva celebrated by his party.

Some key instances stand out when Jaitley determinedly stood by his own views despite pressure from even within his own party. His position on Modi is an example. At the Goa National Executive meeting of the BJP, after the Gujarat riots of 2002, then Prime Minister Vajpayee had made up his mind to give Modi his marching orders. It was a time when the state Congress was in complete disarray. But led by Jaitley, party leaders did not allow the BJP to be swayed by the argument that for the party to survive, Modi needed to be shown the door. In Goa, Jaitley, in steadfastly backing Modi, raised the standard of rebellion against the powerful Prime Minister and the pressure brought from the flanks by NDA ally and then Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N Chandrababu Naidu.

But the battle over Modi was not over and Jaitley continued with his efforts to stymie all attempts within his party to checkmate the high-profile Gujarat Chief Minister in his race to become the prime ministerial nominee. There were insinuations that since Jaitley was handling the cases against Modi, he would use his influence to earn relief for Modi from the courts. But Jaitley, despite all his networking, did not have the kind of influence, or the lack of scruples, needed to circumvent the grip of the Nehru-Gandhi family. That he tried to lobby with the media is a fact. But he failed. For, many of the vocal opponents of Modi continue to hold on to the position they have held since 2002.

What was more remarkable than Jaitley’s endeavours in Modi’s behalf was the resoluteness with which he stood by the man. It was Jaitley who first explored and advocated the abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir, a core concern for the BJP since its inception—and the idea of hollowing it out and emptying it of all substance—completing something that Indira Gandhi had started surreptitiously long ago. The route that the Government took on Article 370 was first explored by Jaitley.

He was also steadfast on the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) although preferring to posit it in the context of gender justice and the urgent need to revoke outdated, regressive personal laws. That packaging was viewed as eminently acceptable in today’s world. It was Jaitley who drafted the 1996 political resolution of the BJP that placed the UCC on the party’s core agenda.

But his cosmopolitan worldview did not allow him to accept Hindutva in its raw form as endorsed by many in his party. He was the first to break ranks with the dominant consensus in the BJP over the rights of gays and lesbians. He also had more sophisticated views on issues like economic reforms. Jaitley was among the first to espouse that self-reliance should not mean autarchic rules of mercantilism. It was his views on economic reforms that ensured he piloted two epic reforms, the GST and the bankruptcy code. It was his conviction which allowed him to push unfashionable causes like demonetisation, the banking and insolvency legislation, or the recovery of non-performing assets (NPAs).

Nor was Jaitley’s cultural nationalism an insecure and paranoid version of nationalism. He was, thus, never comfortable with the stand that Advani took at the behest of career politicians Arun Shourie and Yashwant Sinha to oppose the Indo-US nuclear deal. And he tried very hard and worked from within the BJP to make the deal a reality. Prithviraj Chavan, who was piloting the nuclear liabilities bill, disclosed that if it were not for the timely and intelligent interventions that Jaitley made in the draft law during the UPA’s tenure, the bill would not have been pushed through in Parliament. Especially since the Left parties had opposed it tooth and nail at the time. The bill went through after the Government dropped the words ‘done with the intent to cause nuclear damage and such act’ from Clause 17b at Jaitley’s behest. Without Jaitley’s astute drafting skills, Chavan attested, the Indo-US nuclear deal would have died a quiet death.

Jaitley also moved the 91st Constitutional Amendment Bill suggesting crucial changes in the anti-defection law of 2004. The changes make it compulsory for those switching political parties to resign as legislators and seek re-election upon defection.

On divorce laws, too, Jaitley held progressive views. He was committed to cultural nationalism but his was a conservatism which was more in sync with current realities. Accordingly, his position was a blend of the Sangh’s pride in culture and the demands of modernity, as evidenced in his positions on gay rights and protection of the environment. It was an evolved conservatism. But what would always define Arun Jaitley—and there he clearly stood tall along with Modi—was his unstinting adherence to probity in public life. Jaitley was indeed accessible, helpful and always approachable. But his temperament did not come at the expense of his commitment to probity, as many of his acquaintances in the Congress have realised to their peril.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-OpenMinds2025.jpg)

More Columns

Indian Companies Have a Ransomware Vulnerability Open

Liverpool star Diogo Jota dies in car crash days after wedding Open

'Gaza: Doctors Under Attack' lifts the veil on crimes against humanity Ullekh NP