Mist Is for Mystery

THE END OF cinema-going as we all shift to streaming is yet another wrongly identified trend as this summer has seen "Barbenheimer" pulling in audiences, while numerous Indian films have done so too. Some audiences may have vanished but a certain kind of cinema still pulls in audiences. While films that can't be seen online must be seen in theatres, it is only in a cinema hall that one can enter Barbie's world, feeling as small as a child, and like a child, can dress in pink and sing along. A film about a physicist may seem unlikely to attract large numbers but a Christopher Nolan big-screen depiction of a nuclear explosion is something else. The films even break the rule of shorter films, with Barbie at two hours and Oppenheimer at three.

During the pandemic, home viewing looked to be the new norm with larger screens often having better picture resolution and sound than many cinema halls, the multiplex in particular, with expense and effort minimalised and the feeling of being a viewer rather than audience.

The small screen has also created its own form. Rather than daily or weekly soaps, we now have serials that are tailor-made for binging. The form has clearly intrigued one of the most cinematic of Indian directors, Sanjay Leela Bhansali, who is shooting a Netflix series while Zoya Akhtar has just made a terrific second series of Made in Heaven for Amazon. Akhtar has used the Bollywood hallmarks of lavish sets, costumes, locations, and dance while nurturing brilliant new stars, but has made something unique. There is a startling lack of censorship on issues of sexuality, gender, and language which creates a different reality. Each issue is framed by a wedding but the viewer binges to see the characters develop and reveal their complexity as they face everyday issues, albeit on a grander scale than most of us audience. The two lead characters aren't heroes—Tara is hardworking and ambitious but also a gold digger who puts her own interests first. Arjun exploits his friends and is happy to run up huge debts that others have to pay. Are Adil and Faiza, the nicest characters—although they are shown as liars and unfaithful?

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The pleasure of binge-watching is like wallowing for hours at a time in a big fat novel in which complex narratives develop. The viewers feel they live alongside these characters while having the luxury of being able to rewatch and take breaks around the episode structures. It's the mix of the familiar—a bit of The White Lotus, a bit of Bollywood, a lot of a Zoya Akhtar film—while the characters aren't archetypes but individuals that we get emotionally involved with. And who doesn't love Meher, who keeps her dignity in the face of callous and uncivil behaviour? And Jazz, whose commonsense is her strength but goes astray; and Jauhari, who seems something of a moral compass, is expertly portrayed by Vijay Raaz, one of India's greatest actors.

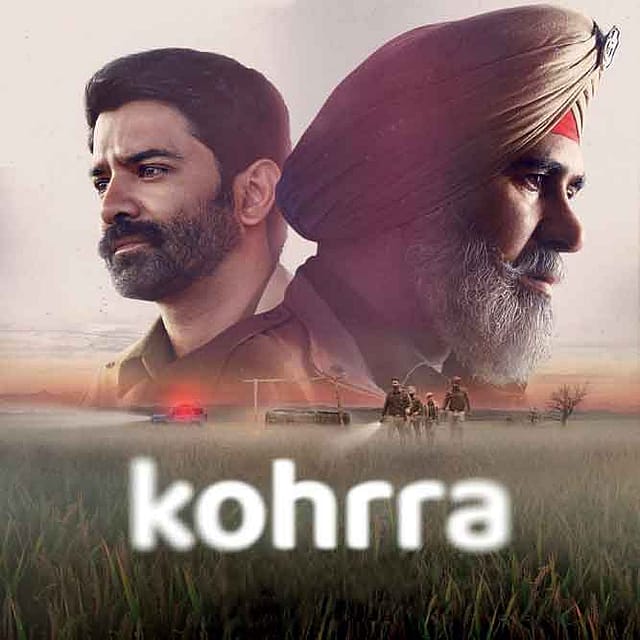

The other series that is truly outstanding, among many excellent ones, is Kohrra, a police drama set in Punjab. Far away from Bollywood or the seemingly unending themes of cool small-town boys with guns, is this well-crafted and brilliantly acted story of complex human issues set across the many worlds that coexist in just one town. The pacing and development of the story and the characters sets it apart from other series and make it at once authentically Punjabi (I think) as well as a global story, rather in the manner of Nordic noir. I was delighted that James Delingpole gave the film a rave review in The Spectator encouraging a wider viewership.

The big, fat Punjabi wedding, the backdrop to the story, never happens. Instead, we have to find our way through the "kohrra" or mist. At first, we see a literal kohrra in which the murder victim is found by a young man who benefitted from the mist to have a secret sexual encounter in a field. Soon, it is clear that the real kohrra is the obstruction to seeing clearly in family and society, as everyone conceals secrets about sex and murder. The police themselves have to clear the mist, but they too have their own secrets to hide.

Drug use and alcohol abuse are manifestations of social problems, but they often mask the real problems that people face when looking for love in the face of society's conventions about marriage, sexuality, and money.

Core to the story is the wealthy Sikh family of the murder victim. One branch is based in the UK but has returned for the planned wedding of the dead man while the other is in Punjab. The two brothers are engaged in a property dispute while their children fight for their fathers' love. One, inappropriately named Happy, is aware that his father loves his cousin more, while the cousin, Tejinder/Paul, fights with his father, Satwinder/Steve, over the right to choose who to love and his religious practices. (The father's decision to use Western names, perhaps to hide identities, is not mentioned.)

The British mother of the missing boy can talk openly with her son whom she accepts for what he is. The NRI boy, Paul, is trapped between his father's views, which are set firmly in his interpretation of Indian values from the past, and the different life he knows from the UK. He has agreed to marry only because he cannot negotiate between the two.

Women's desires are not innocent. They are eager for wealth, consumer opportunities, designer bags, and cars. Veera has given up her DJ boyfriend to marry Paul, whom she barely knows, in return for a wealthy life in the UK. She moves quickly on to the next potential husband. Nimrat's friends tempt her by showing her the consumer goods she has acquired overseas. Is Nimrat's affair also in part because of the wealth of Karan? Rajji wants to keep the family land together and becomes murderous when her brother-in-law, Garundi, with whom she has had a sexual relationship, wants to get married to another woman. Even the policewoman, Satnam, wants to indulge in expensive coffee-based drinks and mobile phones even if they require her to have some secrets of her own.

The main character, Balbir, though no hero, has his own secrets: about his wife's death, the killing of his informant, Nopi, and his relationship with Nopi's widow, Indira. The revealing of Balbir's secrets is key to the plot: he understands that just as Steve's patriarchal views destroyed his family, his own have damaged his but there is still a chance to do a U-turn and move on, not least for the welfare of his beloved grandson.

The characters treasure their secrets more than their families. They are seen to uphold honour by concealing the truth by avoiding shame. Failed masculinity, sexual desire, and homosexuality must be hidden. Silence is preferred to speaking up and honour counts for more than love, even if grief is the consequence.

Secrets also mean that no one will help the police, who rely on torture and imprisonment to try to extract them. Social media, which makes private matters public, and the investigative media are also condemned.

One secret, or thing unsaid, remained throughout the series. No one mentioned the Partition and what that had done to Punjab and how it may have impacted ideas of masculinity or keeping secrets.

One of my favourite jokes was when a bootlegger said he had received a £50 note showing the head of Queen Elizabeth. Garundi slapped him and reminded him the Queen was Victoria. It is, indeed, time to move on.