Márquez’s Love and Other Demons

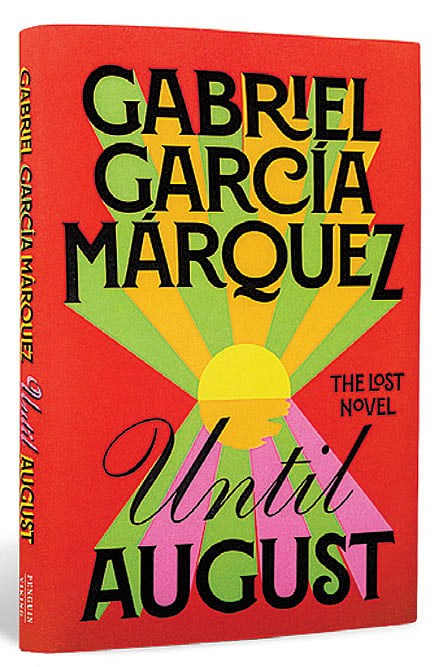

OWNERSHIP OF GREATNESS prompts many transgressions. One of them is the posthumous rekindling of a writer’s abandoned thought—some kind of literary necrophilia that caters to idle curiosity. When an unfinished manuscript that carries on the margins the private frustration of creativity is retrieved from the deeper recesses of the drawers and brought onto the bookshelves, they are not just lofty intentions of the living but the violations of something sacred: the fear of failure felt by a great writer in his autumn. The publication of Until August by Gabriel García Márquez (Viking, 144 pages, ₹799) tells the story of the afterlives of writers, which is larger than the one we read on the pages.

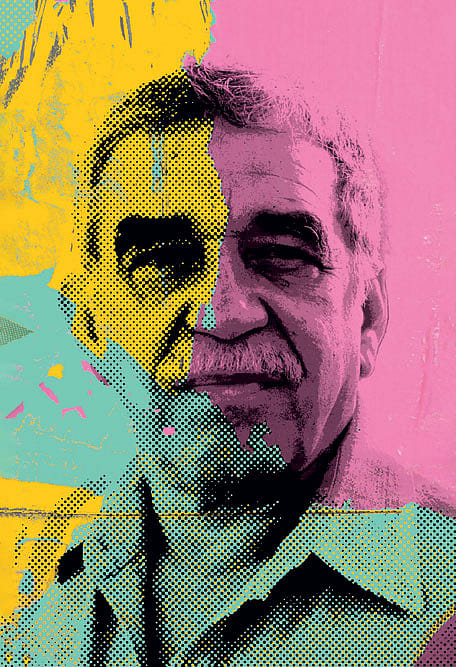

Márquez lost the copyright over the last days of his life with the publication, in 2021, of A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes: A Son’s Memoir of Gabriel García Márquez and Mercedes Barcha by his son Rodrigo García seven years after his father’s death (‘The Last Days of Márquez’, Open August 16, 2021). Elsewhere in Farewell, in a moment when Márquez looks like a character out of one of his own novels, he stands alone in the garden, crying. “Crying? You are not crying,” his secretary asks him. “Yes, I am,” he says, “Don’t you realise that my head is now shit?” He feared the void. He could feel it coming, intimations of a world without the magic of memory. “I work with my memory. Memory is my tool and raw material. I cannot work without it. Help me,” he cried out, even though, in instances of recovery, he was able to joke about this tragic retreat that would deny him the enchantments of another Macondo: “I’m losing my memory, but fortunately I forget that I’m losing it.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Memory for him was like the River Magdalena that runs through Love in the Time of Cholera. In the flow of eternity, lovers like Florentino Ariza and Fermina Daza may finally seek the resolution of a life lived apart, but it’s their maker who swims in it to reach the forbidden gardens of meta-reality. It was in the river of memory that he found the prototypes for fiction’s crazy patriarchs and lonely dictators, haunted lovers and shrinking liberators. And it was on its shores that one of fiction’s most inviting opening lines was born: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

The genesis of Until August as a published work is an intrusion that could only be legitimised by the memory of the living, still unable to recover from the spell of greatness’ shadow they shared. Márquez’s sons in the introduction admit that what this unfinished work brings out vividly is the struggle of a writer who was aware of the inadequacies of his precious tool. “This book doesn’t work. It must be destroyed,” was the great man’s instruction. They defied him, with assistance from his Spanish editor Cristóbal Pera, because they thought their father was anyway in no condition to judge the worth of what he had written. Pera, in an afterword, tells us why a master’s canvas, even if not as perfect as his best, needs to be restored.

In Until August what we get is a miniature world glimpsed through a master’s perforated memory. We see, in flashes of familiar brilliance, the entirety of an emotion’s trajectory captured in an elegant ellipse of language, and a hurried set piece opening the possibilities of existential consolations in a life in which ordinariness is a necessary deception. The story of Ana Magdalena Bach, a woman in her late forties, told in six short chapters, itself is a memorial service played out somewhere in the Caribbean.

Every August, she takes a ferry to an island, checks into a dilapidated hotel, puts aside the items of luxury and turns herself into her “autumnal, motherly” self. With a bouquet of gladioli, she takes a cab to the cemetery, where she puts the flowers on her mother’s grave. Back in the hotel, she would lie on the bed wearing nothing and read Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Later in the evening at the hotel bar, she would listen to sad boleros and try hard to “overcome the humiliation of eating alone.” After a gin and soda, she feels mischievous, and befriends a man from the next table. She invites him to her room, “feeling the delicious terror she had not experienced since her wedding night.” “Why me?” he asks her after the lovemaking. “It was a flash of inspiration,” she answers. She wakes up after a stormy night with the “brutal awareness” that “she had fornicated and spent the night with a man who was not her own,” and finds that he is gone, and she doesn’t know even his name. “Only when she picked up her book from the bedside table to put it in her bag did she notice that he had left between its pages of horror a twenty-dollar bill.”

This horrific finale to a pleasurable adventure makes her a different woman, and in the following Augusts, she seeks the erasure of that humiliation through more one-night stands. No man meets the refinement and tenderness of her first choice—or his cruelty. A voracious reader who prefers the classics to the fashionable, she finds in the furtive eroticism of the island a break from the placid comforts of middle-class domesticity. Music is her family tradition, which continues to be kept alive by her husband, an orchestra conductor, and son, a cellist; her daughter could learn any instrument but opted to be a nun. Her annual, almost ritualistic, escape from home, where traces of unfaithfulness mar the inherited cultural refinement, creates an alternative of love and accompanying demons. The men who feature in her erotic nights only accentuate the memory of the first, and the stigma of which she still carries, with the rage and sorrow of an accidental lover, between the pages of Dracula. If Bram Stoker’s gothic romance makes horror the abiding motif of love’s afterlife, Ana Magdalena’s island adventure turns the shudders of a love story that lasted just one stormy night into private horror the lover is determined to overcome.

In a Márquezian love story, resolutions only magnify the illusions of pursuit. The reckoning for Ana Magdalena comes at her mother’s gravestone on her last visit to the island, when she becomes an appendix to another secret passage of pleasure. Had memory not failed Márquez in his final days, Until August might have grown into a cut-to-perfection gem like Of Love and Other Demons or a masterpiece like Love in the Time of Cholera. (The book Ana Magdalena reads on her last voyage is Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year.) Words that survived a fading memory illuminate the wonders of what-could-have-been and the poignancy of a private struggle. Fiction’s indebtedness to one of its greatest storytellers allows us to read his last sentences in the lingering glow of all that had been written before.

Check out this link: El Realismo Gabo, Forever