Kamala Harris: A Devi for the Oval?

Joe Biden’s choice of Kamala Harris as running mate promises glory for Indian-Americans—but no special favours to India

James Astill

James Astill

James Astill

James Astill

|

21 Aug, 2020

|

21 Aug, 2020

/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Devi1.jpg)

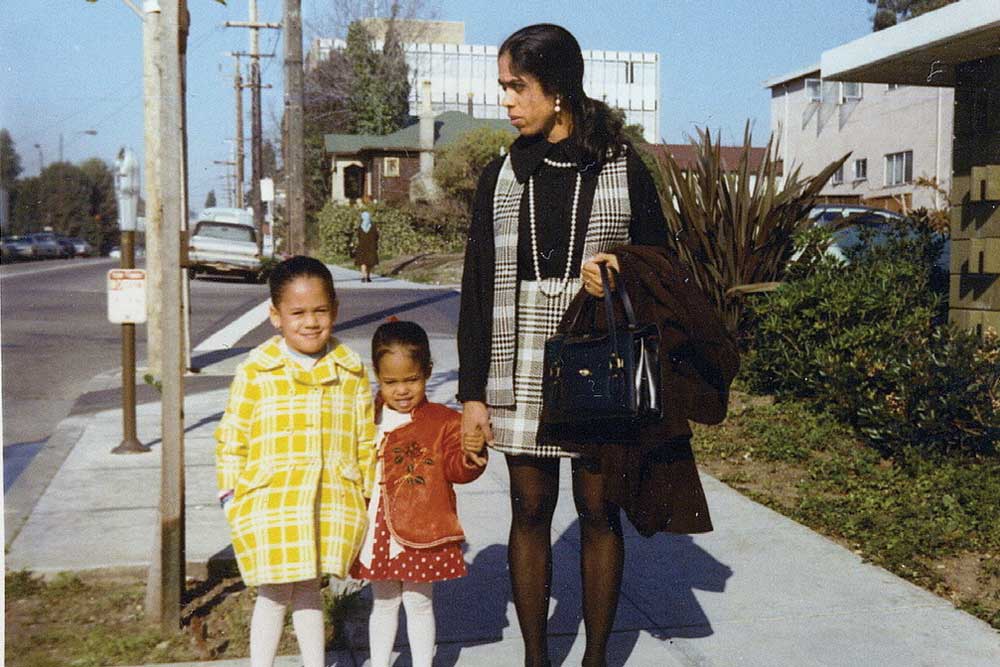

Kamala Harris (Photo: AP)

THE RISE OF Indian-American politicians has been richly championed and celebrated by the assertive and hugely successful South Asian diaspora. But it is not something the first trailblazing politicos themselves were terribly keen to acknowledge. The lead pioneers, Piyush Jindal and Nimrata Haley, former Republican Governors of Louisiana and South Carolina, downplayed their Indian-ness in almost every way.

They changed their first names to ‘Bobby’ and ‘Nikki’ (the culturally ambiguous nickname Haley goes by). Both converted to Christianity, respectively from Hinduism and Sikhism. Both turned against the politics of openness and diversity that their success clearly exemplified. Ahead of his failed presidential run in 2016, Jindal, a son of Indian immigrants, rebranded himself as an immigration hawk and cultural warrior who was “done will all this talk about hyphenated Americans”. Haley became a cabinet member and apologist for America’s most openly racist president in decades, Donald Trump.

It might be tempting to see Senator Kamala Devi Harris in a similar light. Notwithstanding her given names, her adored ‘Tam Brahm’ mother from Chennai and her ability to cook a decent masala dosa (as YouTube viewers can attest), the 55-year-old Californian, who was named as Joe Biden’s presidential running mate, has rarely made much of her Indian heritage.

She describes her late mother, Shyamala Gopalan, a biologist who moved to America for graduate studies in the early 1960s and died in 2009, as her greatest influence. Yet, she has embraced the culture and identity of her Jamaican-American father, Donald Harris. A Stanford University economist, Donald Harris divorced Gopalan when Kamala was seven and appears to have played a minimal role in her later upbringing. Yet, his African-American ethnicity is her preferred hyphenation.

She knows no Indian language. And despite her recent references to childhood visits to Chennai and her Indian grandparents there, she appears to retain little close connection to the country. While taking questions from an audience of Indian-Americans in Las Vegas earlier this year, during her own short-lived presidential campaign, Harris was asked whether she would consider wearing desi clothes at her presidential inauguration. She appeared astonished by the proposal; then said she would not.

American-born desis should not take this personally. Harris’ vantage on India and Indian-ness is quite different from Jindal’s and Haley’s. Indeed, where they sought to diminish their Asian ancestry as a career ploy, Harris has, if anything, come to seem ‘more Asian’ as she has ascended the ranks of American politics.

Her South Asian roots were weaker than those of her Republican counterparts from the start. In the ferment of 1960s Californian student politics, Gopalan and Donald Harris met and together threw themselves into the civil rights movement. And the young Indian researcher retained strong ties to black activism after her divorce. ‘From almost the moment she arrived from India, she chose and was welcomed to and enveloped in the black community,’ Harris wrote of her mother in her recent autobiography, The Truths We Hold. ‘It was the foundation of her new American life.’

Her daughters, Kamala and her younger sister (and now close political advisor) Maya, provided an additional rationale for this. Gopalan understood that race-obsessed Americans would view them as black however the girls dressed or behaved. The concept of ‘mixed race’ barely exists in America and Indian-Americans were not widely recognised in the country back then: the community was only a couple of hundred thousand-strong. Gopalan, therefore, resolved to make her daughters pre-eminently comfortable with the identity America would insist upon. ‘She was determined to make sure we would grow into confident, proud black women,’ Harris recalled.

She and her sister attended civil rights marches from an early age, were left during Gopalan’s frequent work travels with black neighbours and attended their church. The sisters also participated, along with other African-American children, in a controversial effort to desegregate schools by ‘bussing’ black pupils into neighbouring white school districts.

Kamala proceeded to America’s most prestigious historically black college, Howard University in Washington, DC. When she first ran for elected office—as San Francisco’s District Attorney—it was inevitably as a black politician. Several of her associates from that time have subsequently expressed surprise on learning of her South Asian ancestry. It seems it never even arose.

That it has since become widely known is in part testament to the vastly increased presence and influence of Indian-Americans. As their population has surged to over four million, they have graduated from Silicon Valley and Spelling Bees to political prominence. Until 2016, only four Indian-Americans had ever served in Congress. Yet, at least 30 contested primary elections that year; five now serve on Capitol Hill. And the US-Indian relationship has become commensurately more important, further magnifying the community’s clout. Harris’ South Asian heritage was never a secret; it was just something she didn’t talk about, so others didn’t ask her about it. There are a lot of people asking about, and celebrating, it now.

‘Was there ever more of an exciting day?’ the Indian-American actress Mindy Kaling tweeted in response to Biden naming Harris as his chosen deputy. For her and other Indian-Americans, this was a fulfilment of their community’s flourishing in America. Yet their delight is widely shared. Harris is not only the first Asian-American chosen for a major-party national ticket. She is also the first black woman. She is the first Democratic presidential or vice presidential candidate from west of Texas (California’s two Presidents, Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon, were both Republican). Though not young exactly, she also represents a break with the older generation that dominates the Democrats, through Biden, his predecessor Hillary Clinton and the congressional leaders Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer.

In these several ways, she is being celebrated across the left as a pioneer. And the effect is mutually reinforcing. She has come to represent not so much this or that community, as diversity itself: melting-pot America. This is, in a sense, the mirror image of what Biden brought to Barack Obama’s presidential ticket in 2008, as an older white man with a residual strain of social conservatism. His role back then was to reconcile older white Democrats to the party’s first black nominee. Harris’ now is to reassure younger non-white ones, especially women, that Biden’s administration will be more forward-looking than they might fear.

Indeed, given his current strong polling lead over Trump, Biden’s foremost need is to maintain unity within his party’s diverse and often divided coalition. So long as he can do so, he has a strong chance of returning to the White House that he occupied for eight years under Obama. Gratifying for the Democrats, therefore, Harris is turning out to be a popular choice; 83 per cent of Democrats say she is an excellent or good fit.

The inconsistency Harris showed on policy during her own campaign is now irrelevant; her job is not to outline her own agenda but to support the broadly centrist one Biden is offering. And she is amply up to that task. Harris is an attractive, charismatic campaigner. She is also experienced enough to know when to draw back. Her task is to help burnish the 77-year-old Biden’s grand fatherly appeal; it is not to outshine him

Notwithstanding the novelties of her new position, this is despite the fact that she was in some ways a cautious choice. She is not exactly a centrist, as some have called her. Her voting record in Congress is fairy leftwing. Yet that chiefly reflects the prevailing views of her increasingly deep-blue state. When Californians were less leftist (a mere decade or so ago, such is the pace at which demographic change is re-orienting American politics), so was Harris. As a former prosecutor, most notoriously, she forged an early reputation for being tough on petty crime, a position many Democrats now decry as heartless and potentially racist. In her flickering presidential campaign, too, she showed similar pragmatism.

MISJUDGING THE MOOD of her party, she entered its primary contest earlier this year as a self-proclaimed radical, promising sweeping healthcare and other reforms. Yet, once it became apparent that most Democrats over-ridingly wanted to beat Trump and considered radicalism a distraction or even an obstacle in the way of that goal, she changed course. This perhaps makes her vulnerable to a charge of opportunism. But pragmatism in the pursuit of victory, which is opportunism by another name, is what most Democratic voters crave—as their selection of Biden, a respected but unexciting presidential candidate, clearly indicated.

This also makes Harris’ political skills look helpful to him. The inconsistency she showed on policy during her own campaign is now irrelevant; her job is not to outline her own agenda but to support the broadly centrist one Biden is offering. And she is amply up to that task. Harris is an attractive and a charismatic campaigner. She is engaging in a way that, for example, Hillary Clinton’s chosen deputy, Tim Kaine, another likeable but unexciting Democratic moderate, never was. She is also experienced enough to know when to draw back. Her task is to help burnish the 77-year-old Biden’s grandfatherly appeal; it is not to outshine him.

Drawing on her courtroom experience, she is also an articulate and tough debater who will not be cowed by the slurs Trump and his cronies are already throwing at her. (The President has aired a palpably bogus conspiracy theory that, as the child of immigrants, Harris is not eligible to be vice president.)

Notwithstanding these strengths, she is unlikely to have a material impact on the result of the election. Presidential running mates almost never do. There is some evidence that they can boost the candidate’s prospects in their home state. Yet California was already safely in the bag for Biden, with or without Harris on board. Even so, she looks much more like a potential asset to Biden than a liability—as, for example, Sarah Palin, an embarrassingly callow Republican Governor, was to John McCain in 2008. And that in itself speaks well of the Democrat’s judgement.

Especially as the most memorable moment of her short-lived presidential campaign was when she attacked Biden for his past opposition to ‘bussing’ as a means of desegregation. It was one of the most jarring moments of the entire primary contest. By picking Harris, Biden appears to have turned it into an opportunity, however. One of the main arguments for his candidacy was that he was uniquely able to reconcile the Democratic coalition. His apparent willingness to set Harris’ barbed comments aside might seem to underline that promise.

For generally left-leaning Indian-Americans, Harris represents a sort of trade-off. She is one of their own—and therefore a symbol of their community’s remarkable rise to the heights of American business, media, entertainment and politics. She also represents promise of an even greater prize. The Economist’s election forecast model, based on a vast assortment of polling and other data, suggests Biden currently has an 87 per cent chance of beating Trump in November. And if he does, he has already suggested he would want to make Harris an unusually high-powered deputy.

IN A JOINT APPEARANCE with her last week, he said: “I asked Kamala to be the last voice in the room. To always tell me the truth, which she will. Challenge my assumptions if she disagrees. Ask the hard question. Because that’s the way we make the best decisions for the American people.” This was essentially the role—of chief presidential truth-teller and confidant—that he played for Obama. It gave him a prominence on the left that he is leveraging still. And if Harris played her cards right, it might put her even closer to the top job than it did him.

Indian-Americans are within an imaginable short series of steps from making it to the Oval Office. Yet, Kamala Harris’ membership of their tribe comes with qualifications. She appears scarcely to have registered it until fairly recently. She has also shown no particular interest in US-India policy—and even less encouragement to the current BJP government in New Delhi

If elected in November, Biden would be the oldest first-time president. As such, he might well decline to run for a second term. In the normal run of things, this would make Harris the favourite to succeed him. No wonder her unveiling on the Democratic ticket made Kaling giddy. Indian-Americans are within an imaginable short series of steps from making it to the Oval Office. Yet, Harris’ membership of their tribe does come with qualifications.

As noted, she appears scarcely to have registered it until fairly recently. She has also shown no particular interest in US-India policy—and even less encouragement to the current BJP Government in New Delhi. Back in October 2019, after it revoked the special status of Indian-administered Kashmir, she issued this warning: “We are watching.”

That reflects the prevailing sentiment towards India among most mainstream Democrats. They are robustly behind the bipartisan and decades-long policy of ever-closer US-India ties. They would also be expected to treat the bilateral relationship less carelessly than the Trump administration has, on trade especially. Yet, they would probably be more hectoring and outspoken in their criticisms of the Narendra Modi Government, on civil liberties in Kashmir and otherwise. And, in the event of a Biden-Harris administration, Harris’ Indian ancestry would not make a jot of difference to that. Biden would call the shots on foreign policy. And even if he did not, Harris would be unlikely to diverge from the centre-left consensus on US-India diplomacy. Asked to choose between the broad sentiment of her party and lobbying from the pro-BJP Indian-American lobby, she would go with her party every time.

Indian-Americans could not claim to be let down by this:

Harris has given them no reason to expect otherwise. But lest any come to feel underserved by her, they might console themselves with this intriguing—in fact, rather astonishing—possibility.

Among the Republicans who are already jostling to succeed Trump, Haley is very much in the mix. And if the President were to lead his party to a bad defeat in November, it might well turn to her brand of conservative moderation. That would push her even further to the head of the Republican pack. It is, therefore, not at all hard to imagine America’s presidential election four years from now as a choice between two Indian-American women.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-OpenMinds2025.jpg)

More Columns

Puri Marks Sixth Major Stampede of The Year Open

Under the sunlit skies, in the city of Copernicus Sabin Iqbal

EC uploads Bihar’s 2003 electoral roll to ease document submission Open