Blame It on the Totem

IT IS EASIER THAN ever to get afflicted by Democracy Derailed Syndrome. If you are still immune to the disillusionment that lies at the root of the affliction, you are likely to be accused of a cynic's nonchalance or a bigot's affiliation to an immoral political belief—and I'm not sure which is worse now as we are all ideologically indexed and arranged to suit the other's righteousness or rage. Losing faith in democracy is not an extreme form of withdrawal from political engagement any longer.

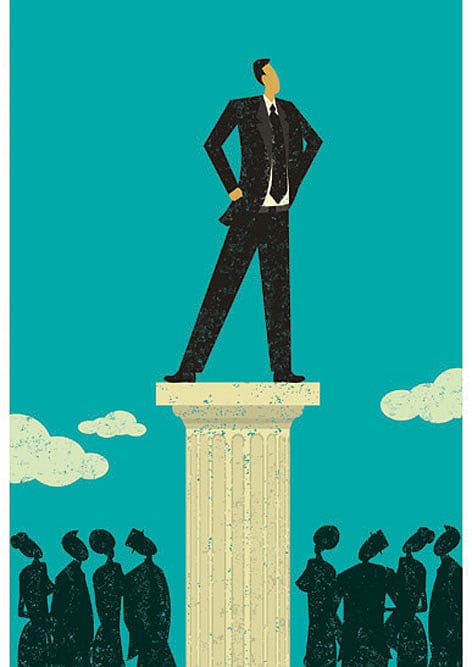

January 6 on Capitol Hill, Washington DC, marked the severest rupture in faith, for the Trump supporters' storming of the US Congress was more than an American transgression in democracy. It was the instinctive expression of a new kind of politics, more totemic than ideological, and Trump, the highest totem, was beyond the natural laws of democratic verdicts, beyond defeat; he was the permanent winner. Totemic leaders in politics cannot afford to be rejected or measured on a moral scale by the doubters. The storming of the Capitol was a last desperate surge for the totem shaken by democracy's judgment.

Two years on, with unintended commemorative rage, supporters of a defeated ultra-rightwing populist stormed the parliament, the supreme court and the presidential palace in Brazil. The aborted coup, January 6 rearmed, was, in most analysis, the new export of American values in democracy—or the universalisation of Trumpism. Jair Bolsonaro, the defeated president, was Trump reimagined by a Latin American fabulist—or so went the comparative studies in populist autocracy. As democracy became an item 'stolen' by the liberal establishment in the storytelling of the ultra-right, it also lost its credibility—and even useability—in the eyes of the morally disillusioned. DDS was inevitable.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

DDS grew in parallel with the rise of the totemic leader, who was born in the wreckage of politics-as-usual with its rusty left-right division. While the left was fast losing its captive class, and the right its copyrights over conservative values (in society, economy and governance), the usurper was claiming the abandoned constituencies, and the 'centre' was certain to fall to his promise of a new deal. The totemic leader feasted on resentment, weaponised grievance, and monopolised the future.

He was there before a Trump or a Bolsonaro, in varying versions of the authoritarian deliverer-cum-über nationalist. But they flourished in stifled civil societies; institutions could only take the cue from their paranoia. They were genetically linked to their great-dictator predecessors but without their empires, imagined or real. The arrival of Trump, in the ultimate land of freedom and rights, was a new beginning, and nothing has been the same ever since.

In him merged all the traits of the totemic leader in a fully evolved democracy. The new party establishment, which itself is a repudiation of conventions and common decencies, is built on the leader's fears and fantasies. The system will always be obedient to the totemic leader. In the alternative reality of totemic democracy, loyalty is equality, rejection is assertion, and truth is a permanent dispute. Trump's Republican Party has dismantled the last vestiges of Reagan-Bush elitism and replaced intellectualism—bye bye neocons—with anti-factualism. Everyone beyond the fold was a suspect in the subterranean conspiracy against the new leader, the anti-leader. To lose an election is to be robbed by the conspirators. Trump thought so. Bolsonaro, too.

The Trump era intensified the debate about the unravelling of democracy and the unmaking of liberalism, and both verged on alarmism. The so-called populist, whether from the left or the right, is a master of the politics of inversion. The populist puts the base—the newly empowered drawn from both sides of the ideological divide—before the leaders. And he keeps the base intact by painting the present black and exaggerating the future. He bypasses institutions because nothing but his instinct is worthy of his trust. His rise, as told and retold by pundits, made the liberals redundant—and liberalism passive—and democracy as a system untenable.

Both prognoses are premature. The problem with liberalism—or the actually existing version of it—was, as the American thinker Mark Lilla argued, the liberals' tendency to mistake evangelism for action. The liberals began to enjoy the power of counterargument more than power itself. And of democracy, what we see today is not the unravelling but a reminder of its tenacity and elasticity. In its journey, it has survived many totems in various political cultures, and every time sending Cassandras into a paroxysm of dread. The perversions and pathologies of totemic leaders continue to be misread as exhaustion of democracy itself. The Bolsonaro story ends with the eventual irrelevance of Bolsonaro; it doesn't influence the future course of democracy.

That said, totems persist in democracy because they are the harvesters of popular impatience. No system other than democracy sustains the impatience—the original catalyst for change.