‘If you give people the right to information, they will be ready to donate’

Varun Sheth, Founder, Ketto

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

|

01 Nov, 2018

|

01 Nov, 2018

/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Ketto.jpg)

Back in 2015, a man in Mumbai named Siddhant Dand set up an unusual campaign on the crowd-funding website Ketto. His target: to raise Rs 315. His aim: to buy himself a pizza.

The campaign was a joke, of course. The concept of using the internet to tap a crowd of strangers was still somewhat new in India. And it was yet to take off the way it has now—as a means not just to raise money for dire needs like medical emergencies or during natural calamities, but for a host of other less vital things like fundraising for a startup, making a film, writing a book, travelling somewhere, or, yes, even buying a pizza.

On Ketto today, there are campaigns by some who want money to buy a dog, some against the use of plastic straws. There are campaigns to improve roads and fill potholes. One that is bringing out edible cutlery, and another which is as ambitious as wanting to eradicate poverty.

All this is precisely how Ketto’s founder Varun Sheth, 30, views the platform. “I may think it doesn’t work and people won’t be interested in it. But that’s not to say it shouldn’t be there,” Sheth says. “[A campaign] can be anything—social, commercial, maybe even silly. I get guys here who say they want to raise money to build an aircraft larger than the Airbus A380. Obviously [this campaign] won’t succeed. But hey, who am I to say they shouldn’t try and raise funds?” The only types of campaigns the platform forbids, Sheth says, are those meant to raise funds to contest elections. Some candidates, usually independents, eyeing local municipal council and state assembly seats have tried to raise such funds in the past, but they have not had much success.

In terms of reaching his target, Dand’s pizza campaign turned out to be a big hit. He raised over Rs 2,000, though all he wanted was Rs 315, leading him to promise that he would use the extra money to buy pizzas for others.

Sheth hadn’t always conceptualised his platform to be used in such a way. When he first began to work on the idea of a crowd-funding website, Sheth thought the platform would be primarily used by entrepreneurs raising money to fund their startup ideas. “I really thought that was how it was going to be—a place for entrepreneurs to at least raise that initial capital. The initial seed funding is most difficult for startups. Once you raise that, then it is easier to scale up,” he says.

A year into its existence, it became clear to Sheth that the platform was going to prove far more successful as a place where money could be raised for any purpose. Startup entrepreneurs raising money comprise only about 10 per cent of all campaigns on the platform today. The most popular, making up at least half of all campaigns, are individuals seeking public help for medical expenses.

Today, Ketto is one of India’s leading crowd-funding platforms. So far, it has conducted over 50,000 campaigns and successfully raised more than Rs 300 crore. It has over 1 million donors on its platform currently and over 10,000 NGOs as partners. A year ago, on an average, the platform used to raise about Rs 5 lakh across its various campaigns. Today, it does more than Rs 20 lakh every month. This too, Sheth says, is shooting up.

Crowd-funding is not new. There have been platforms in several countries long before Ketto showed up. But what has been remarkable about Ketto is how it has managed to convince Indians, not known to be a particularly philanthropic people, to open up their purses and donate generously. Its efficacy in matching donors with recipients did the rest.

There is this belief that Indians are not giving by nature. But I don’t think that’s true. People give in India. Just very differently, says Varun Sheth

When Sheth first began to work on the idea of Ketto in 2011, Indian tightfistedness was a big worry. “Everybody was telling me, ‘Why are you doing this?’” he says. “‘Don’t you know, Indians don’t give?’”

Sheth, only 31 years old, has a lean physique with a scraggly beard. He has a cheerful disposition and a somewhat slovenly appearance. He sits at an unremarkable desk among several of his employees in a room. He points out that he has been working for several years, starting when he was only 14 years old at his father’s plastics and paper manufacturing business in Gujarat.

By 2011, he had completed his college education. He had failed, however, to get his father interested in sponsoring him to pursue a course abroad, like some of his friends had managed. (“You didn’t study in your college here,” his father told him, “what are you going to study there?”) Sheth began work as an analyst in a financial firm instead, something which he didn’t particularly enjoy. Eight months into the job, his department shut down and he lost his job. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to go back to Dad’s paper business… [and] I didn’t want to do a job just looking at numbers on a screen for ten hours and returning home.”

So Sheth spent the next four months as a backpacker on a trip across Himachal Pradesh. It was around this point, he says, that internet mobility was taking off in a big way and he began to consider a possible business around crowd-funding. At one point on his trip, he chanced upon a local organisation running a school in Manali. “The school needed to raise some money. And I wasn’t doing anything, so I decided to help them. We just put up [a request for donations] online. Facebook was getting popular. So it was there. Then we put up pictures, sent emails, very basic stuff, said this is what’s happening, ‘Please support.’ It got very good traction. We had lots of people sending bank drafts,” Sheth says. In all, the school raised over Rs 10 lakh. “I realised then that if you tell people, if you send them the right information, they will be ready to help,” he says.

That is what his gut told him. And that is what his experience with the school had now shown him. But nobody around him thought so.

“There is this belief that Indians are not giving by nature. There was very little online transaction happening then. And everyone used to tell us, ‘Firstly, nobody gives here. Secondly, nobody shops or does any transaction online. Donation kab hoga (When will donations happen)?’” he says. “But I don’t think that’s true. People give in India. Just very differently. They give to temples, to people around like maids and drivers, or the guy on the street. We just need to walk 10 metres to find poverty in India, unlike the West.”

“The challenge thus is in making all this unorganised giving into something organised,” he says. “That’s what we are trying to do. To give a receipt, to give updates, to engage people with causes, show them the history of what they have done. The challenge is in all that.”

“It’s not like people don’t give here,” he says. “You just need to be transparent and you need to tell your story well.”

About 90 per cent of the people online in India don’t speak or read English. Once we roll out more languages, we should be able to tap much larger crowds, says Varun Sheth

The Ketto platform first went live in 2012. When he first began reaching out to entrepreneurs, there was very little interest from them. “But the non-profit sector was far more excited. They wanted to figure it out,” he says. A year later, the actor Kunal Kapoor who wanted to work on something similar in the non-profit sector, came on board as a co-founder. In 2014, a third co-founder, Zaheer Adenwala, joined in.

For over a year, Ketto was entirely bootstrapped. No one was willing to invest in it. “We must have been rejected by more than 100 investors. We tried everywhere, all the big cities—Mumbai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Bengaluru. But nobody thought there was a workable business model here,” Sheth says. The platform finally managed to raise $120,000 in December 2013 from a recently-established angel investor network called Calcutta Angels. “They had just set it up. It was Kolkata, so I guess maybe not too many people were going and presenting [business ideas] there. So we had little competition,” he says. Two years later, Sheth managed to raise another $700,000 from a group of investors.

In the first few years, the platform achieved very little traction. Its first big success came in December 2013, when it managed to raise over Rs10 lakh to send the luger Shiva Keshavan to the Sochi Winter Olympics 2014. Next came over Rs 6 lakh for Shweta Katti, the daughter of a commercial sex worker in Mumbai, then only a teenager, who had won a scholarship at New York’s Bard University. She needed the money to cover additional expenses.

During this period, since Ketto had not yet hired any employees, Sheth was involved in every aspect of the operations. This involved not just running the website and persuading organisations to put up their campaigns on it, but also writing pitches and putting up photographs and videos.

What became clear from the success of those campaigns, Sheth says, is not just that the stories of the campaigners and their campaigns have to be interesting, they also need to be told compellingly. “It is not enough just to tell people what they need the money for. You need to tell it properly. And unfortunately, very often people don’t know how to do that,” Sheth says.

Ketto is headquartered in Mumbai. It has an office in a building that is still under construction in Andheri, a suburb. It has some employees in other metros, but most of them work out of the Mumbai office. Here they chalk up strategies, follow up with organisations and individuals and check on the progress of their campaigns. They also have an army of content creators on the ground whose job is to create stories around campaigns. “These people tell the story. And then later they go back to see what happened to those stories, they check what kind of impact was created, they even do an audit.”

Ketto is now a well-oiled machine. During natural calamities, the platform works with remarkable speed and clarity. Within hours of learning of a disaster, the team would have contacted several relief-focused NGOs for ground reports on what is most urgently needed. Multiple campaigns covering various geographical locations and needs in the affected zone would be up and running soon after. Ketto raised over Rs 1 crore cumulatively after the 2015 Nepal earthquake. Earlier this year, during the Kerala floods, the website raised over Rs 2.3 crore.

According to Sheth, Ketto has only just begun to scratch the surface of the platform’s true potential. Next year, it will be rolling out campaigns in several Indian languages, reaching out to people in India’s smaller cities and towns. “Right now, there are campaigns from across the country, but they are only targeting the English-speaking crowd online. About 90 per cent of the people online in India are supposed to be those who don’t speak or read English. So once we roll out more languages, we should be able to tap much larger crowds,” Sheth says. Ketto also plans to start operations in Thailand and Indonesia by next year. There is also talk, Sheth says, of partnering with local organisations in Italy and Nigeria to bring out local versions of the website in those places.

Visiting Ketto online offers a snapshot of India in all its busyness and energy, its dreams and anxieties. There is proof of the country’s glaring failure to take care of the health and education of its people. There are stories of crippling debt and misfortune. But there are also wonderful little stories. Of acid attack victims scripting a new life, of people climbing Mount Everest, of athletes of obscure games competing in international events, of poor parents wanting to give their children a good education.

The digital age is often criticised for isolating people from one another. But the likes of Ketto are managing to harness the very technology that is blamed for this isolation—the internet—to build bridges and foster empathy and love among strangers.

One of Sheth’s favourite stories is from last month. An NGO called Uday Foundation had set up a campaign to help the family of a manual scavenger, Anil, who had died while cleaning a sewer in Delhi. This was immediately after the image of a child, Gaurav, grieving in front of Anil at the crematorium, had gone viral on Twitter. Within a span of a few days, around Rs 57 lakh was raised for the family. The money was to be retained in fixed deposits until Gaurav and his two siblings turn 18, the monthly interest until then serving as cover for their day-to-day expenses.

It later turned out that the child wasn’t Anil’s biological son. He had been in a live-in relationship with a woman named Rani, who had children from a previous marriage. Anil’s biological relatives wanted the money instead.

The NGO and Ketto, however, decided to retain the money for Gaurav and his siblings since Anil was in a live-in relationship with Rani and treated her children as his. “So we put the information out there. And we told [donors] that anyone who wanted to withdraw their donation was free to do so,” Sheth says. “But apart from one or two people, nobody withdrew their donations. They said they don’t care if he wasn’t their biological father.”

Also Read

The Wealth Issue 2018: Complete list of Essays and Profiles

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

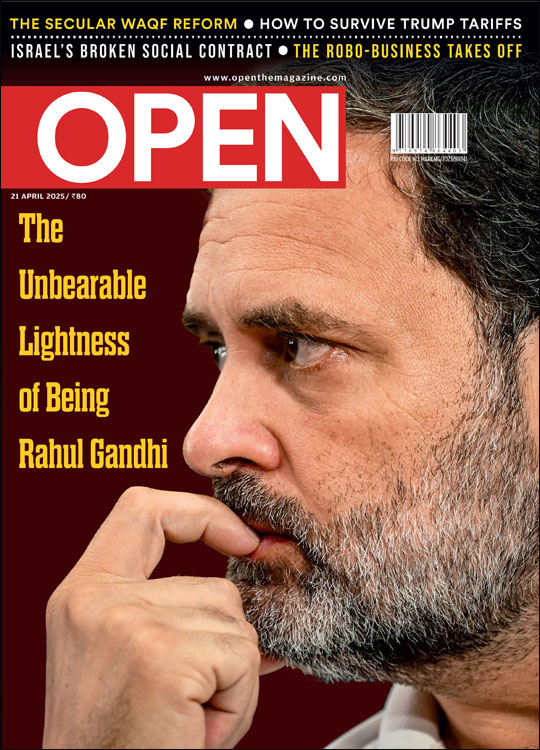

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

The Numbers Game V Shoba

MS Dhoni’s investment in Gensol suffers a blow amid financial scandal Open

Dhankar takes on judiciary over ruling on President powers Open