Souza’s Gaze

SCHOLAR AND CRITIC Janeita Singh’s study FN Souza: The Archetypal Artist (Niyogi; 320 pages; ₹4,500) is a labour of love. Twelve years in the making, it distils her deep engagement with the Indian-born artist’s life and work into a form that is at once rare and refreshing in the realm of academic art writing.

Like her subject, Singh breaks out of the mould of academic stodginess, bringing her eclectic, often eccentric, personal choices into the narrative. The occasional use of the first-person voice conveys a sense of authenticity, while highlighting her responses as a woman to Souza’s lifelong immersion in women’s bodies. There is even a chapter written in the “Souza’s voice,” an experiment that doesn’t necessarily land, but still deserves to be applauded for breaking the monotony of the third-person commentary. Singh’s approach is also a striking contrast to the foreword by art historian Debashish Banerji. Liberally strewn with phrases like “monstrous posthumanism”, “anatomical index of cruelty”, and “The noetic and the alchemic are carried on the waves of the pneumatic,” such turgid jargon has done a huge disservice to popular engagement with art criticism.

The starting point for Singh is the “uneasy space” Souza opened with his graphic depiction of the female anatomy on canvas. His intrepid gaze on women’s bodies documented their progression through cycles of maturity, change and decay, turning lithe and grotesque at different junctures of their lives. It wasn’t the kind of decorative art that collectors could flaunt on their drawing-room walls. As a result, despite being one of the leading lights of the Progressive Artists’ Group, Souza had little success during his life. Posthumously, his work has fared better at auctions, with The Lovers fetching $4.89 million in 2021.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Among the many reasons behind Souza’s lack of success, compared to his much savvier contemporary like MF Husain, was the trail of controversies that plagued him throughout his life. As a young artist in London in the 1960s, and later America, he was dismissed by critics for work that was derivative of the modernist masters. The accusation had some merit, considering the influence of expressionist, fauvist, and cubist styles in Souza’s youthful work, but the sentiment was also tainted with racism. Then, there was Souza’s tumultuous private life—two wives, two partners, several children—a mix of bohemian and philandering recklessness that frequently left him in penury, at the mercy of the women in his life, who dutifully looked after him, in spite of the ups and downs in their relationships.

A further strand of Singh’s study emerges from Souza’s personal mythology of embracing the image of the inspired artist, a heroic Coleridgean man with “flashing eyes” and “floating hair”, around whose art she weaves “a feminist reading… with an equal thrust on its study through a Jungian lens and Eastern- Western philosophy.” If these twin focal points, feminism and philosophy, are the distinguishing marks of the book, they also become its nemesis, in a sense.

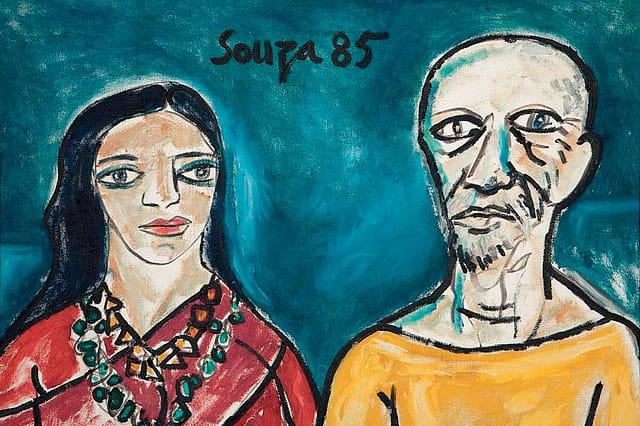

The public perception of Souza’s art is informed by his obsessive interest in the female nude. It’s hard to think of many artists who sketched, painted, and drew bare-bodied women with as much vigour as him, stripping away the coy and curvy aesthetics of Renaissance art (the reclining Venuses and the spotlessly perfect Biblical women) and the Victorian prissiness of Raja Ravi Varma, to reveal voluptuous bodies in full frontal view. Women, in Souza’s art, are not only founts of virility and sex, but also terror and power. Singh links back this vision of the female body being a repository of strength instead of nubile fragility to several key moments in the artist’s life.

To begin with, Souza’s childhood, spent under the care of his widowed mother and grandmother, left a formative mark on his psyche, which would become even more complicated by his exposure to Japanese Shunga manuals, the Kama Sutra, images of Krishna Leela, where the blue god tricks the milkmaids and steals their clothes as they bathe in the Yamuna. Souza’s imaginative universe turns like a kaleidoscope, revealing ever new patterns of the East and West interacting, colluding, and coalescing into each other to define his unique visual language. “My painting,” he would go on to say later in life, “is a product of my libido.”

To this melting pot of influences, Singh adds the potent ingredient of Jungian psychology and comes up with another layer of meaning based on the workings of the artist’s “anima”. “The anima according to Jungian philosophy is the feminine within a man’s psyche,” as she explains, “most active in visionaries, prophets and shamans responsible for understanding of the irrational, earth and nature as well as the dark unconscious.” Singh maps Souza’s journey of individuation as an artist on this definition, reading hidden meanings into his work that reveal him not as a voyeur, but rather as a votary of the immense potential that lies repressed inside feminine energy.

From the cults of the Mother Goddess to the veneration of the Virgin, Souza’s reference points shifted restlessly across cultural, religious, and sociological contexts, often within the same painting. While this intellectual catholicity gave him a visually rich vocabulary, many of the esoteric foundations of Souza’s art were most likely lost on commoners and critics alike. Singh’s unpeeling of the sources bring to light Souza’s farsightedness (long before Beverly Whipple’s identification of the G-spot in 1976, the artist was already depicting women in throes of orgasm) as well as his patently subversive outlook. Birth (1955), one of his most iconic works, shows a man assisting a woman in labour, her head and neck pierced with spikes and nails like a suffering Christ; his face stoic and patient, acting as the midwife. The artist’s gift of creation seems to pale into insignificance before the woman’s power to create new life.

While Singh’s investment in Souza’s art is sincere throughout the book, her desire to connect cultural dots, from far across time and geographies, may create a sense of historical dissonance. It isn’t unusual, for instance, to find a quote from Jacques Derrida, followed by a passage from the Vedas, references to tantra, Husserl and Nietzsche rolling in one after the other within a few pages. This parade of random citations has the unfortunate effect of reading like a string of interesting thoughts, decontextualised from their origins and not quite synthesised into the narrative as a whole.

There is, however, a more fundamental question that begs grappling with. It’s undeniable that Souza left behind a rich and varied body of work, especially the chemical alterations he made on mixed media and the abstracts he painted in the early phases of his career. But how unique are his female nudes today? A cursory survey of the book, with its proliferation of women of similar appearance and posture, begins to pall on the eye, with only the occasional exception standing out for its sharp edginess.

It’s worth reflecting why artists like Francis Bacon, whose influence is palpable in some of Souza’s best work, flourished and left behind a legacy that shines to this day, while Souza’s prolific oeuvre doesn’t enjoy a similar purchase in the annals of art history. Racism is, undoubtedly, a big part of the story—but it isn’t the be-all and end-all of it either.

More crucially, from the vantage point of the 21st century, how are we to make sense of Singh’s praise for Souza as a feminist artist, the inveterately promiscuous man who liberated the female figure from the confines of propriety and enabled its full flowering before the public eye? Amrita Sher-Gil, who predates Souza by some years, had already set the ball rolling with her exploration of women’s lives, bodies and, most of all, their interiorities, which would eventually go on to fuel the Progressive’s Boy’s Club.