Locked Down in the Studio

In the present standstill, artists are grappling with the urgency of art and the non-essentialism of artists. Rosalyn D’Mello captures their moments of turmoil and tranquillity

Rosalyn D’Mello

Rosalyn D’Mello

Rosalyn D’Mello

|

17 Apr, 2020

Rosalyn D’Mello

|

17 Apr, 2020

/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Instudio1.jpg)

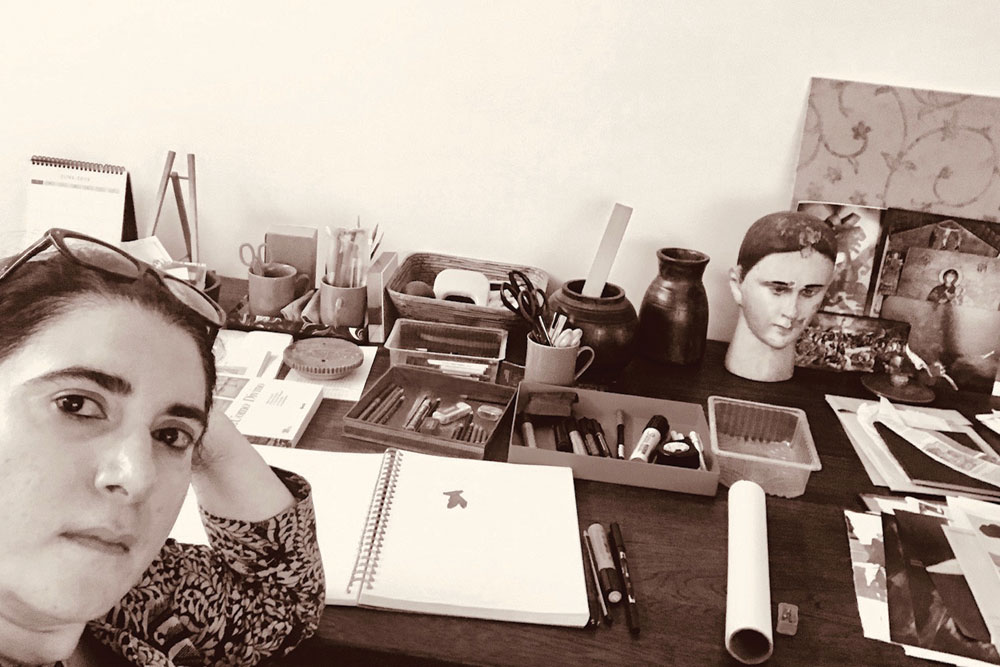

Priyadarshini Ohol: ‘I’ll make site-specific work. I’m good at adapting. That’s one of the reasons why I call my art agile. I’m a bit handicapped in the sense of my usual style, but I will make do’

AS WE MOURN our delusions of normalcy, those whose identities had been constructed around the profession of artmaking are confronting a unique dilemma. On the one hand, a sudden deluge of time. The lockdown has arrested the global movement of artworks and impeded the usual functioning of festivals, biennales, art fairs and even exhibition displays at galleries. The standstill has left many artists with time enough to make art, uninterrupted by non-self-determined scheduling. Yet, the circumstances of the mass quarantine serve as an impediment to the pursuit of being productive. The inability to foresee what the world might even look like post-coronavirus only aggravates the irony, compelling artists to question their own priorities and to reflect on what fuels their emotional bandwidth. I can relate to their conundrum, considering I had planned to spend almost all of 2020 visiting South Asian artists’ studios. Only recently did I come to terms with being clueless about when I might be able to resume my fieldwork. It’s a peculiar situation, considering I’m unable to even visit the studios of artists who live in the same city as I.

Anjum Singh, whom I was scheduled to visit on March 8th, in her Delhi studio, texted me three days before to indefinitely postpone our meeting. ‘My pulmonologist has asked me to keep minimum contact and of course avoid stepping out etcetera,’ she said. Given the fragility of her compromised immune system, on account of her ongoing battle with cancer, I couldn’t but be understanding. ‘We shall meet as soon as this calms down,’ she added and attached, to cheer me up, a photograph of her gorgeous fourlegged companion, a black Labrador she named Rufus.

The sight of her canine friend reminded me of another animal-loving artist, Adip Dutta, who was scheduled to open his solo show at Experimenter in Kolkata, in April. When I had last visited him in February, in his south Kolkata studio, he was in the throes of finishing work. He had spoken then, as he had spoken before, about what he had longed for most—the solitude afforded by unbroken, uninterrupted time. Since he is a fulltime faculty member of the visual arts department at Rabindra Bharati University, this longing was inflected by the recognition of creative bandwidth consumed by teaching.

When we spoke over the phone a few days ago, we both chortled over this irony, of being given ‘time’, yet having to contend with the meaning of making any work of art in this moment of contagion. He confessed to no longer keeping track of what day it was. “It’s a very strange, surreal sort of thing,” he said. He corrects himself after first using the word ‘meaningless’ to describe the heft of his artistic conundrum. “Before, I had a context, a life. I would go out for sketching and drawing. I’d come back home [which doubles as his studio] and make the drawings. Now we’re all living like captives, so this whole process of making these drawings, the ones based on a certain kind of input you would gather, that whole process has been disrupted. It’s very difficult to focus on what you were doing… If you ask me, I will get down to work and produce drawings, but what is the whole point of doing it?”

Dutta spends much of the day cleaning, washing, cooking. He doesn’t describe this as a very artistically productive time. He is, however, reflecting on existential, political issues and even mundane, domestic happenings that otherwise loitered around the periphery of his consciousness. One of his most profound recent encounters involved his sighting of a three-and-a-half-ft-long snake in his verandah. It was surreal. Similarly, he is wrestling with the present complexity of elements of his routine that he had taken for granted before, like sourcing meat to feed his pack of adopted strays who are constant presences within his workspace. To maintain his hand, or “keep the practice on”, as he puts it, he continues to make drawings, though the scale of his otherwise meticulous output has evidently shrunk. He describes this daily discipline as a process of making lines, not necessarily art. He remains uncertain about when his scheduled solo might open and, if and when it does, wonders what form it’ll assume. What would it mean for them to hang in a gallery without the validation of human eyes.

He narrated how a friend had recently observed that his drawings, mostly devoid of human presence, resembled the vacant look of locked-down metropolises. But Dutta is aware that was never the intent behind their creation. “To look at something within a situation, that is what makes certain things relevant,” he said. “I won’t say it’s become irrelevant… the whole process of making those drawings, that is still relevant, that makes sense—holding the magnifying glass, etcetera, that is important to me, but what I was looking at, that has to be reviewed again.” Dutta is also increasingly troubled by the politics that mark our present, the criminalisation of Muslims, the marginalisation of migrant labour, the citizenship law issue. He finds himself reconsidering, more and more, the physical part of art production: “The idea of using your own body in the making, which becomes default, when you’re not left with any option.” Though he was always physically involved with work, he still relied on collaborators for help. “Then you knew how to outsource, but now you have to scale down,” he added. “I don’t know whether that’s good or bad, but that’s the situation.”

MITHU SEN, WHO lives in south Delhi, has had to experience her own fair share of irony. She had returned from her studio in Faridabad, in Haryana, on the night of the janata curfew. “All was fine, but by 9 PM, it was declared that from next morning, the lockdown would happen. The border was already closed, so, by default, I am at home,” she said over the phone. She describes her present reality as being “in transit” or “in halt”. After initially going through what some psychologists have construed are indeed akin to the stages of grief, Sen seems now at peace. “I have no FOMO [fear of missing out]. I’m not thinking anything, just that when I survive this so-called metaphorical thing that’s happening, I will actually take all the techniques that I know, the skills I can practice, either as a cook, or a draughtswoman or sculptor, and I might continue to use them, but as a hobby, I doubt if I will call them art.”

One could argue that this is a typical ‘Mithu’ response, considering the foundational tenets of her practice include radical hospitality, counter capitalism, linguistic anarchy and tabooless sexuality. But something feels different about her tenor. She spoke calmly about how she’d spent the last couple of years proselyting, through her performance art and drawings/sculptures, the trap of consumerism and the delusions of market. Sen also imbued the format of the contract with more than a hint of satirical humour. “My first contract in 2017 declared that all my tangible art forms are actually byproducts, without giving any clue of what the main product would be, if there is any.” Sen, who believes her preferred medium is life itself, perceives many seemingly mundane things as byproducts, like going to the washroom, bathing or eating. She has found a measure of relative tranquility because she believes that over the past years she had already been mentally changing her behavioural patterns of being an artist. “Now, this lockdown is physically giving me the balance. And there is, very surprisingly, no fear of death, no fear of having to breathe my last breath. As a human being, I am concerned about parents, and those sentiments can drive me crazy. The social situation disturbs me so I cannot sleep at night—seeing labourers walking, dying, not having food. I am redefining the privileged position and its relativity, how it allows that I can stay at home and live for three months more than someone on the street. I think the relativity is a matter of time… whether I am living a week or a month extra than that man or not. So I can see the world is slowly collapsing and rebooting, and I, rather, will be ashamed if I survive physically.”

Sen refers to the past, even in its most immediate form, as a pre-corona time, and during that span she had already arrived at a point where she had internalised that the source of her joy was the process of thinking and reflecting on life. She had already begun the process of slowing down, saying no to opportunities that would have fuelled a more jetsetting lifestyle. “I’m feeling so relieved that I don’t have to force my body or mind for anything. I’m like a pre-civilised person or animal. I just need to search for food for the day to survive. It’s a new beginning, a new life, and it’s very empowering.”

At home, separated from her Faridabad studio, Sen is being more alert to how her body inhabits the site of its domesticity. “I’m almost sitting in the same place in the whole house,” she said. “There was an initial restlessness about breaking the routine, now I’m going to my wall, seeing the switchboard and thinking [about] how many times I turn the switch… small things overlooked by my consciousness are giving me room for introspection.” Neither is her home turning into a studio, nor is her studio turning into home. “But I am turning into something which has no definition yet, my mind is going through a transformation. It is transcendence, without the religious or spiritual dimension,” she said, adding that she felt honoured, proud and happy, even privileged. “I am in it.”

Unlike Sen, Manmeet Devgun, who sustains her livelihood by doubling as an art teacher to schoolchildren, is lucky enough to have access to her studio, despite the lockdown. However, she struggles with finding the time and energy to inhabit it, since it is housed within her apartment in Vasant Kunj in Delhi. Devgun is a single mother of a pre-adolescent child, and so, her experience of quarantine is complicated by the erasure of divisions between her role as a caretaker and as an artist. ‘Sometimes it is a dragging one hour, sometimes it’s a fast-forward day,’ she said over email. ‘When the lockdown started, it was a bit hapless. I was not sure if I should tend to the kitchen, or the house, or just put everything on hold and sit in the studio. With a kid at home, there are different priorities, obviously.’

EVENTUALLY, SHE FOUND that since she doesn’t have to ‘go to work’ or drop off her child, Brishti, at school, she is able to create. Her studio practice is thus taking on a different form. ‘I’m able to use different materials which I had just stored up in the cupboards! Not that I’m producing or creating extensively, just some paper play and enjoying it. I think, for an artist to be able to be in the studio itself is a great feat!’ she added. As a single parent, the lockdown has offered a chance for enhanced mother-child intimacy. The day is spent trying new recipes, fighting and making up. Devgun confesses she has more unfettered access to solitude now than before, since she’s not out of the house running errands all the time and so, has a lot more energy shored up for creative pursuits.

Anju Dodiya can also access her studio located downstairs in the same apartment block in which she lives in Ghatkopar, Mumbai. However, she goes there daily just to water her plants after which she returns home. ‘Somehow, I still haven’t had the desire to clean up and get to work,’ she said over email. Dodiya’s solo, Breathing on Mirrors, had opened at Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, on February 29th, and was scheduled to run until April 30th. It was forced to shut down midway. Dodiya’s sense of perspective holds her afloat amid her grief. ‘The sadness of imagining a year’s work hanging in a dark, inaccessible space is nothing compared to the tragedies unfolding around us,’ she wrote. She spends her time cooking, cleaning and reading. Every evening, she, along with her husband Atul Dodiya and their daughter Biraaj, whose debut solo, Stone Is a Forehead at Experimenter, Kolkata, also had to be closed prematurely, watch movies together. ‘[We’re] mostly revisiting the classics that I devoured and learnt so much from as a young person… Bergman, Kurosawa, Antonioni.’ Seen ‘afresh’, after a gap of decades, Dodiya says she finds she has new opinions on these old crushes. She isn’t dwelling on her professional setbacks—cancelled talks, group exhibitions, art fairs, etcetera. ‘Apart from the uncertainty of the working calendar, I think I feel grateful that I could simply continue to draw and paint quietly if this continues,’ she added. ‘After all, that is what artists always do… Be alone with your work.’

However, not all artists have had either the privilege of being quarantined in their studio or even the luxury of inhabiting their own home. For those who, for the sake of their practice, had perhaps been at the right place at the wrong time, the sense of irony is further compounded. For instance, Vidisha Fadescha, a trans-disciplinary artist-curator, DJ and founder of Dragery, a social gathering questioning gender, queerness, fetish, phobias and representation through drag, has been stranded in Australia. Fadescha was in Sydney when the world began to progressively be locked down. They had been invited to install their exhibition titled Burn All the Books That Call You the Unknown as part of a festival that was to be held mid-March but was cancelled. At the time, Fadescha was waiting on a few formalities and had wanted to explore the Sydney Biennale. They were scheduled to return to Delhi by the end of March when the 21-day lockdown was instituted and India closed its airports. Their next flight back home is now scheduled for May. But Fadescha is well placed, in that the project space that invited them, offered to continue to host them, allowing them to access the studio, too.

DESPITE BEING miles away, for Fadescha, the Covid-19 battle in India has always had a personal dimension, since their mother works at a government hospital that was among the first to host patients showing symptoms of coronavirus infection. “The doctors have still not been provided PPE and even personal protection are not allowed to be brought, so my sister has set up a fundraiser to get them protective gear.” She is hoping to raise money for the cause “as this fight is not getting over anytime soon”.

Hope, for Fadescha, lies in our potential to think of ourselves as collectives, rather than as individuals, and to reflect on how one’s action affects another’s wellbeing. “The artist has to be adaptable. And the artist has to understand intersections,” they said.

Like Fadescha, Priyadarshini Ohol’s artistic practice is enmeshed with political activism. She calls it ‘artivism’. As a Dalit, even though she may sometimes inhabit the same space as members of the ‘art world’, she is conscious of her otherness, of being “a misfit in the world of rules and hierarchies and market economy”.

I had waited a whole week to contact her, because she had intimated seven days before, at midnight, that she would be embarking on a silent fast in her attempt to ‘go inwards’. She had much to process. She had been awarded a studio residency from Pro Helvetia, slated for October this year, and had been living her life under the assumption that she would leave for Europe around then. Until January, she had been in Dharamshala, in her studio in Dhasa. But the intensifying anti-citizenship law protests and incidents of police brutality drew her towards Delhi.

The coronavirus threat was looming. Deciding to be cautious, she chose to remain in Delhi and not return to Dhasa, a tough call to make, as Ohol knew she had, waiting for her in Dhasa, a fully functional studio residency, with canvases prepped on the walls and materials already in use. Unable to bear the dearth of these, she sourced some stretched canvas from an old supplier and bought whatever colours were available, however non-synchronous they seemed. She doesn’t even have the right brushes. ‘But it’s okay, I’ll make site-specific work. I’m good at adapting. That’s one of the reasons why I call my art agile,’ she wrote. It is more the conceptual mindspace she misses about her studio in Dhasa. ‘I have a setup there. It isn’t fancy, very basic, but is a sort of life I’ve designed in which I’ve invested four years worth of things and materials I’ve used, notes, colour charts, references that I don’t have here. So I’m a bit handicapped in the sense of my usual style, but I will make do.’ The self-imposed silent, meditative, fasting retreat was instituted to facilitate her transition ‘back inwards’ and was not envisioned as a means to the end of creating. ‘I stayed in silent contemplation or meditation and worked on making the space mine. For a while, I rolled up the canvas until I needed it. I’m warming up to it,’ she wrote and confessed that she was still processing the recent Delhi riots.

For the week that she went inwards, she didn’t communicate at all and went on a food fast for four days, heard no music, stayed away from the internet, woke up at 4 AM, meditated, tried to bring stillness and deal with all the emotions brought on by the pandemic and examine herself. Ohol wishes to take this reflection further and evolve it either as a longer solo performance or to initiate an open-space collective around it.

Ohol hopes that when we emerge from the lockdown,we learn to see the unseen and invisible and make rules and policies from the bottom up. ‘In India, the virus was brought primarily by oppressor castes and classes and they are now sitting inside their homes in gated complexes while the greatest havoc has already started being wrecked on the common Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi working class, daily wager, labourer,’ she wrote. ‘They will die cleaning sewers, taking out trash, sanitising, sweeping, cooking, delivering things to people in homes, or farming, nursing sick people. What a sick society! I hope noone is well adjusted to this ever.’

In a moving essay published on Medium, titled, ‘The Forgotten Art of Assembly’, a recently unemployed theatre practitioner, Nicholas Berger, reminds us that ‘this is a humanitarian crisis, not an artistic one’, as he argues against the recent rush to use the digital medium to fake normalcy when we should, in fact, be mourning its death. Though speaking specifically about theatre, he manages to isolate the basic insecurity at the heart of the present existential irony confronting most artists: the internalised wisdom about the urgency of art and yet the non-essentialism of the artist. ‘We’re being asked to exit the stage, not give an encore,’ he writes. ‘When the world rebounds and we push our heads out from the rubble, and there will be rubble, we will seek each other out with a renewed sense of gratitude.’

Click here to read all Coronavirus related articles

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

India hammers Pak air bases at Rafiqui, Murid, Chaklala, and Rahim Yar Khan in a show of unflinching force Open

How India (re)built its defence preparedness and war readiness V Shoba

Cracks in the Pink Fortress Open