Ancient India through William Dalrymple’s Lens

The golden land in black and white

Shaikh Ayaz

Shaikh Ayaz

Shaikh Ayaz

Shaikh Ayaz

|

29 Oct, 2021

|

29 Oct, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/AncientIndia.jpg)

William Dalrymple, photographer and author

AS A HISTORIAN, William Dalrymple stands out as much for his rigorous research as for his evocative writing style. Dalrymple also wears the hat of a photographer and in his images, you see some of the same qualities. A man consumed by wanderlust, the best-selling author of City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi, White Mughals and most recently The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire travels to ancient sites far and wide to excavate ghosts of the long-buried past for contemporary consumption. It seems the crumbs of his trails that don’t quite make it to his weighty tomes (no Dalrymple book can be described as ‘slim’) go to his photographic folder. And from there, they are now making an outward journey towards art galleries eager to explore a side of Dalrymple’s that his readers are perhaps less familiar with.

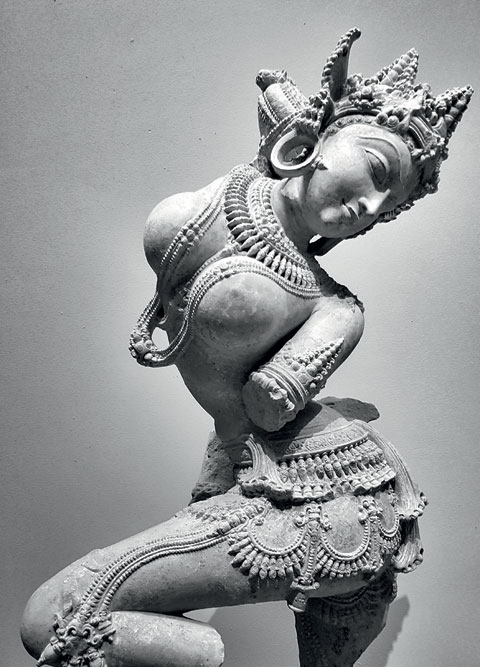

All of July, London’s Grosvenor Gallery had displayed a selection of Dalrymple’s black-and-white photographs as part of its show The Traveller’s Eye: Photographs by William Dalrymple. The 56-year-old festival director of the Jaipur Literature Festival who lives on a farm near New Delhi is currently displaying his art closer to home. The ongoing In Search of Ancient India at Vadehra Art Gallery, Delhi, is a visual glimpse into the research for his forthcoming book The Golden Road. For the project, Dalrymple revisited heritage landmarks around India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Sri Lanka. Along the way, he captured photographic impressions of architectural and cultural marvels that have remained hidden in plain sight for centuries. Even a traveller as seasoned as Dalrymple can sometimes come back with a feeling of awe and wonder when encountering an old place on fresh inspection. For example, this time around he was especially impressed when he rediscovered the rock-cut Bodhisattvas of Gandhara, the monumental Pallava sculptures of Tamil Nadu, the Badami Chalukya architecture of Karnataka, the Kushan period artefacts of 2nd and 3rd centuries and Gupta sculptures of the 4th and 5th centuries. It only serves to prove that ancient India was one of the world’s “greatest aesthetic and spiritual civilisations,” says gallerist Roshini Vadehra. More than a decade ago, Dalrymple had reflected in Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India, “In Western art, few sculptors—other than perhaps Donatello or Rodin—have achieved the pure essence of sensuality so spectacularly evoked by the Chola sculptors, or achieved such a sense of celebration of the divine beauty of the human body.”

With these images, I am going back to two of my teenage obsessions — I was a keen photographer and spent my life in dark rooms, developing all my black-and-white pictures. And in my summer holidays, I used to go to archaeological excavations to dig, says William Dalrymple, photographer and author

With In Search of Ancient India and the in-progress The Golden Road, he returns to some of the same ground — only more ambitious in scale and scope this time. Both projects hope to tell the world how the Indian artistic, architectural and cultural influences spread across Southeast Asia and then through much of the rest of the world. From about 200 BC to 1200 AD, India was home to a sophisticated culture where creativity flourished alongside trade and economics. During this golden period, India became an exporter of its own civilisation in all its forms rather than being the one at the receiving end of external influences. “In a sense, what you see in this show is the seed which produced this extraordinary harvest so far away from India, in places like Thailand, Malaysia, Burma, Cambodia, Sri Lanka and interestingly, even China,” Dalrymple tells Open from Corfu, Greece.

“For instance,” he continues, “the Pallava sculptures of Tamil Nadu have a lot of influence in Burma and Malaysia, the art of Amaravati in stupas of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, the art of Guptas in Cambodia and so on. Lord Vishnu wearing a mitre that you find in Mathura can also be seen in Thai sites. Much of this influence was obviously intermixed with local reception but still, you can see a burst of monumental Indian art that inspired other civilisations in so many different forms, symbols and contours.” The most intriguing links are those between the Pallava architecture in Kanchipuram and early Cambodia. In legend, there are supposed to be marriage alliances between the two distinct cultures but “the details of the contact have so far eluded historians and archaeologists.” And then, there is the mighty Pallava script, considered to be the mother of all Southeast Asian writing systems.

It’s a matter of scholarly debate how these influences travelled. Most likely, it bounced through the usual channels. Itinerant missionaries, spice merchants, Brahmins, mathematicians, astrologers, sculptors, traders and craftsmen from India left behind their cultural signposts as they passed through Southeast Asia. “It could be portable images, whether they were bronzes, ivory, wood or sand. The Chinese travellers mention buying Buddha figures and bringing them back to China. These served as the model for the later Tang period. By 660, Buddhism became the state religion of China under the empress Wu Zetian — the only woman to rule in her own right in the long span of Chinese history. With it came a whole explosion of Indic learning, art and civilisation. It’s amazing, especially when you consider how self-confident Chinese culture has always been and how contemptuous they have usually been of other cultures,” says Dalrymple. A traveller and translator, Xuanzang was one of the many Chinese Buddhist monks from the early 6th century who traversed 6,000-miles on a pilgrimage and manuscript-gathering expedition to the great Indian centres of learning. Impressed with what he saw, he wrote, “People of distant places, with diverse customs generally designate the land they most admire as India.”

In a sense, what you see in this show is the seed which produced an extraordinary harvest so far away from India, in places like Thailand, Malaysia, Burma, Cambodia, Sri Lanka and interestingly, even China, says William Dalrymple

The photographs included in the show are a mix of landscapes, sculptures and close-ups, often against the backdrop of archaeological ruins. “Many of the sites, such as Mahabalipuram and Hampi, are located in very dramatic scenery. Bellur, Ajanta, Ellora, Udayagiri, Aihole, Badami… all these are spectacular locations and retain a wonderful sense of the glories of that past,” says Dalrymple who has devoted the last segment of The Golden Road to Indian mathematics and astronomical discoveries and its transit.

Long before Dalrymple thought of becoming a historian, he was entranced by photography. It runs in his blood. His great-great-aunt Julia Margaret Cameron is considered one of the early pioneers of portrait photography. “It was truly my first love,” he admits, adding, “With these images, I am going back to two of my teenage obsessions — I was a keen photographer and spent my life in dark rooms, developing all my black-and-white pictures, and in my summer holidays, I used to go to archaeological excavations to dig.”

Born in Scotland, India is his spiritual home, a country that he first visited in 1984 and has lived in since 1989.

“Before coming to India, I was an enthusiastic student archaeologist. I dug all over Britain and wanted to study an Assyrian site in Iraq but Saddam Hussein closed down the dig as well as the British School of Archaeology where I had planned to be based. So, I ended up coming with a friend to India. That changed my life completely.” He is still attracted by some of the things that made him fall in love with India in the first place. “As a kid in the 1980s, I was most excited by sites like Ajanta, Ellora, the Gandharan sculptures, the early Buddhist sites like Sanchi, Takht-i-Bahi, Taxila and Anuradhapura. Today, I find myself reverting to my younger self and immersing boisterously in these ancient worlds.”

As a teenager obsessed with the art of photography, Dalrymple’s role models were Bill Brandt, Don McCullin, Sebastiao Salgado, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Fay Godwin. From them, he learnt his artistic motto — stare intensely and deeply into your subject’s soul and for the moody chiaroscuro effect, nothing can beat black and white. “I always preferred black and white, partly because it allowed me to develop and edit my own prints; but mainly because black and white seemed a much more daring and exciting world, full of artistic possibilities,” he wrote in The Guardian in 2016. “It’s not like I don’t use colour,” he tells us now. “I photograph family pictures and just general social media stuff in colour. But for serious photography I always prefer black and white. I learned photography from looking at the works of Bresson, Brandt, McCullin, Salgado and they all worked in monochrome. I hugely admire Steve McCurry but for me, black and white is the real thing.”

Dalrymple regales one with stories of his childhood idol Don McCullin. He’s spent the last few days in the company of the celebrated British war photographer in Corfu. “I sat at his feet for a week, very much the chela with the guru, talking to him about his travels in Cambodia and Vietnam and his process and his impressions of Robert Capa, Bresson and Salgado,” he gushes. McCullin had recently come back from an epic trip through Turkey when they met. “I just hope I am like him when I am 86 and have his energy and humour,” Dalrymple adds.

(In Search of Ancient India by William Dalrymple runs till November 3rd, 2021 at Vadehra Art Gallery, Delhi)

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba