The Critical Insider

Writer and politician Javed Jabbar tells the tale of his tangled relations with the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and Benazir Bhutto

Mani Shankar Aiyar

Mani Shankar Aiyar

Mani Shankar Aiyar

|

30 Jan, 2022

Mani Shankar Aiyar

|

30 Jan, 2022

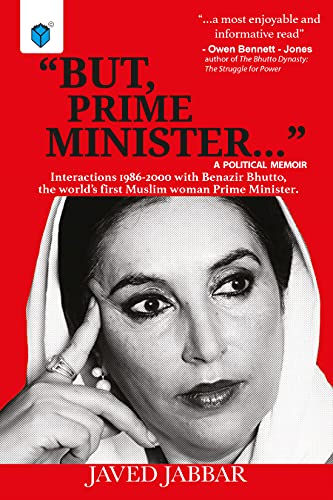

/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/BenazirBhutto-1.jpeg)

Benazir Bhutto (Photo: Getty Images)

It is strange to be reviewing for an Indian audience a book that is not to be found in any Indian bookshop or library but has been at the top of Amazon UK’s bestseller list. Indians cannot even order it on Amazon—and we are the only losers of this bureaucratic blindness for it keeps us from getting under the skin of our most important—albeit troublesome—neighbour. There is a need for Indians interested in Pakistan to be informed of an inside view of Pakistan politics in the last three decades by an insider who never quite made it into the inner circle or, to put it another way, an outsider who managed to edge his way inside. I suggest those who might be provoked by this review into reading the book get a relative who lives in the West to bring it into the country

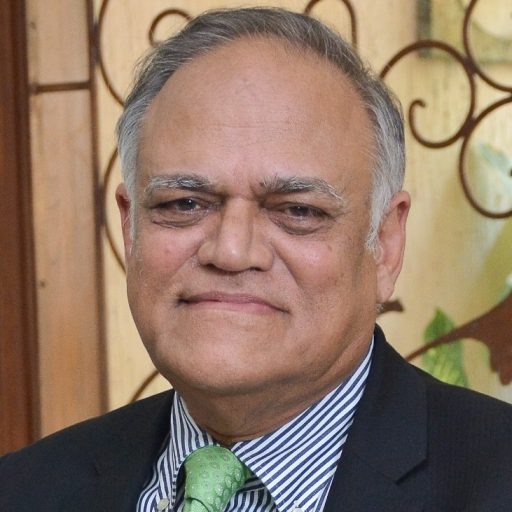

Javed Jabbar, a prolific writer in the public space, was never really a politician in any meaningful sense of the word, but was a well-known public persona for most of his life, he has been not only a senator but also a minister with a variety of portfolios—Information, S&T, Petroleum, National Affairs—in Pakistan governments of different hues. Now, as he wheels into his late seventies, he tells the tale of his tangled relations with the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and Benazir Bhutto as the first of a series of books that will come out this year and the next of Pakistan under its other rulers, including particularly Farooq Leghari and Pervez Musharraf. Of course, in doing so, he begins his story a few years before Benazir Bhutto became prime minister in December 1988 and a few years beyond her assassination twenty years later in December 2007.

The author of But, Prime Minister… explains that the title was suggested to him by a friend who attended Cabinet meetings where Jabbar would often preface his expression of views contrary to the Prime Minister by saying, “But, Prime Minister…” It is an excellent title for a political relationship that was more constructively adversarial than slavishly obedient. He had his own view, was not a career politician and, therefore, as a “technocrat”, free to take it or let it go. It is this that adds spice to a tale that might have been that of a “jiyala”, what we in India more usually call a “chamcha”.

While Jabbar, whom I got to know well when I served in Karachi as India’s first Consul-General (1978-82), was sceptical of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s many shenanigans, he was appalled at the “unjust, inhuman” treatment meted out to Bhutto, leading to his hanging on April 4th, 1979, an event that shocked and scandalised most Pakistanis (indeed, most of the world). Nevertheless, he was not ready to give himself over to wholesale condemnation of Gen. Zia-ul-Haq which was the fashion of the day and could, therefore, accept in all conscience the opportunity to enter the Senate from Sindh in one of the five seats reserved for “technocrats” in the party-less elections of 1985. He, however, preserved his distance from the military establishment by becoming a vocal member of the Independent Opposition Group that did not hesitate to use the cloak of Parliamentary immunity to fire fusillades at the Zia dictatorship.

As an excellent orator in both English and Urdu (but perhaps more so in English) he soon came to public notice as an unusually frank but constructive Senator, and thence to the attention of, among others, Benazir Bhutto when fortune smiled on her with the death of Zia in an as-yet-unexplained freak air accident on August 17th, 1988. A few weeks later, she became Prime Minister and invited Jabbar to relinquish his “Independent” status and join her Party prior to appointing him as her Minister of State for Information reporting directly to the PM.

While others with a longer history of suffering for their membership of the PPP, especially following Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s judicial (but hardly legitimate) hanging, somewhat resented Jabbar’s proximity to the Prime Minister, he got on with attempting to dismantle the structure of Government propaganda, mistakenly labelled “information”, that previous governments, particularly the Zia dictatorship, had structured. Since he had only ten months in office, it is astonishing how much he got away with in the teeth of opposition from his fellow-ministers and the somewhat tepid support he received from his Prime Minister: restoring the editorial independence of the State-owned leading English daily, Pakistan Times, and the Urdu Mashriq; ensuring an overall mix of perspectives in the public and private print media; allowing Pakistani journalists to go abroad without requiring them to obtain “No Objection” certificates from the Ministry he headed; abolishing the “black list” that prevented major public personalities from access to State-controlled audio-visual media; formation of a Wage Board for newspaper employees after a gap of several years; ending newsprint quotas which had become both a major source of corruption and an instrument for keeping media proprietors on a short leash; and, above all, guaranteeing time on news broadcasts to Opposition views, thereby bringing down on his head the wrath of his ministerial and party colleagues. He even proposed renaming the Ministry as the Ministry of Media Development. (It actually came to be named a variation of that suggestion for a brief period at his suggestion in the Caretaker Government, 1996-97, in which Jabbar served as minister of petroleum, but was later, after he had resigned his post as Adviser, reversed by Pervez Musharraf).

He called his radical reforms a “new news policy” and answered his critics, including the Prime Minister, by saying that whatever the short-term political fallout of the new news policy, in the medium- and long-term its consequences could only be beneficial, pointing to the fall in numbers of Pakistanis listening to BBC (and All-India Radio) to get some sense of what was really happening in their country.

The new news policy led to four run-ins with the Prime Minister. On the first occasion, it was not Benazir but her mother, Nusrat (in Benazir Bhutto’s presence), who lashed out at Jabbar for letting Nawaz Shariff’s “scurrilous” charge of “atheism” against Benazir (a grave offence in fiercely Islamic Pakistan) run in its lead headline for Pak TV: “What kind of freedom have you given to PTV and Radio Pakistan? To freely broadcast all kinds of lies and slander about BB?” thundered the PM’s mother.

On another occasion where Jabbar had arrived without, it turned out, the explicit authority of the Prime Minister, Benazir snapped at him, “Javed, what are you doing here?”

A third gentle slap on the wrist followed at her press conference on returning from the Kuala Lumpur Commonwealth Summit in October 1989 when Jabbar, moderating the press conference, infringed standard protocol asking for questions before the PM had made her initial remarks. She interrupted him: “Javed, I will first make my statement, and will then take questions”.

The fourth and most serious run-in was over Jabbar’s proposal that licenses may be issued, after due diligence, to the private sector to run TV channels parallel to the State channel. He was informed that the “competent authority” did not approve. So, when he tried out the proposal in person, arguing that “freedom for the media is like a bitter-tasting medicine” but eventually good for the Government, she “closed further discussion” with a “sceptical smile”.

I was so reminded of the reprimands I had received at Sonia Gandhi’s hands, especially after she named me minister!

The break, however, came in July-August 1990 when Jabbar found that in contravention of his policy of allocating Government advertisements strictly on the basis of laid down objective criteria, phone calls were being made by Benazir Bhutto’s PMO to individuals nominally working under Jabbar to favour or disfavour certain journals. Infuriated at this suborning of his authority, Jabbar sent in his resignation in July 1989, but Benazir insisted on his remaining in her council of ministers. Jabbar suggested that he might be considered for junior minister in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (an excellent suggestion because he would have come into his own in MFA). However, the minister, Sahibzada Yaqub Khan, did not endorse the suggestion. And so Jabbar proposed himself for what we in India would call “independent charge” of Science & Technology, a low-profile yet highly important portfolio.” He remained in that post, occasionally speaking out of turn (“But, Prime Minister…”) till the government itself was dismissed in August 1990.

I comment little on his tenure as Minister S&T because I do not know much about science or technology but would like to dwell at some length on an issue that brings out the best in Javed Jabbar. It had little to do with his ministry and everything to do with his origins as an Urdu-speaking immigrant from India, a muhajir. There had been a riot provoked by the PPP’s then deadly opponent, the MQM, in Hyderabad, Sindh, to quell which the Sindh government had ordered the police to shoot, in consequence of which several lives were lost, including women and children. This had inevitably ignited strong flames of resentment against the original Sindhi-speakers of Sindh. Jabbar and another good friend of mine, Makhdoom Khaliquzzaman, scion of a leading Sindhi family of religious and political leaders (who was delighted by my description of him as the “Sanjay Gandhi of Sind”—but before Sanjay was killed in an air accident!), had made public statements separately condemning the atrocities against innocents. This was played up as tantamount to condemnation of both the PPP government of the province and the PPP government at the centre, leading to veteran elements of the PPP castigating both Jabbar and Khaliq for crossing party red lines.

Hence, at the start of the next National Assembly session in Islamabad, PPP members were asked to assemble and Benazir’s political secretary, Naheed Khan, strode in with a message from the Prime Minister for her party legislators: “You must also strongly condemn the statements by Makhdoom Khaliquzzaman and Javed Jabbar.”

Jabbar, standing at the rear of the members crowding the hall, called out, “Certainly Naheed sahiba. Your advice should be followed. Do condemn me. I look forward to your speeches.” That silenced them. The two offenders then waited during the session that followed to be condemned by their fellow party legislators, “but found that, charmingly, Naheed Khan’s advice, doubtless at the behest of her even more charming Prime Minister, had the opposite effect. Not a single PPP legislator named us”. Javed Jabbar adds, “For the record, and to her credit, Benazir Bhutto never referred to my dissenting public criticism of Government”. Similarly, I might just mention, Sonia rarely referred to my criticism, as a minister, of some of our government’s policies, especially on economic policy. The parallels are uncanny.

But, Prime Minister… is an excellent title for a political relationship that was more constructively adversarial than slavishly obedient. Javed Jabbar had his own view, was not a career politician and, therefore, as a technocrat, free to take it or let it go

Matters came to a head in a post-mortem meeting held in Benazir’s Karachi home a few weeks after the wholly unjustified dismissal of her government in August 1990. While party elders were reviewing reasons for the reverses suffered by the party, Jabbar spoke out about the image of corruption that had badly tarnished the party’s reputation. “In an intense, very annoyed tone, her face frowning and her eyes focused on me, she said, ‘Corruption? Of course not, Javed, there was no corruption. Give me one example, show me some evidence. Don’t just echo what our enemies claim.’” With that ended his relationship with Benazir Bhutto. He was not even sounded for a ticket to fight Senate elections when his term ended in March 1991 and then, following a futile attempt to be elected as an Independent, there came a long period when he was side-lined in the PPP (as I have been in the Congress). “For me,” says Jabbar, “this was a time when one was torn between deep disappointment and alienation on the one hand, and on the other, a sentiment of solidarity”. To no avail. “Benazir Bhutto did not give a party ticket to me for election at any point thereafter.” Nor, it seems, did Jabbar ask for one. The parallels in our respective political lives stun me!

The next Benazir Bhutto government was formed in 1993 and lasted till 1996. Jabbar was not included in it. He went back to his profession as honorary chairman of arguably Pakistan’s premier advertising and communications agency. During this time, he learned to his horror that Bhutto had awarded the contract for Pakistan’s first FM radio and TV channel, without prior public notice inviting bids, to a firm owned substantially by a friend of her husband, Asif Ali Zardari. Jabbar challenged this blatant act of nepotism and corruption in the Supreme Court and although it was expected that he would be given only a couple of minutes, he was listened to with care for all of 45 minutes by a full bench of the court headed by the Chief Justice. While the case eventually went into the doldrums, as do so many similar cases in both of our countries, the breach between Jabbar and Bhutto became irreparable. This was compounded by Jabbar being hounded by the Federal Investigative Agency repeatedly raiding the offices of his NGO doing excellent work in the areas adjacent to the Thar desert just as a way of personally harassing him. This could not have been done without Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto’s implicit or explicit connivance. Nevertheless, when there was an unexplained kidnapping attempt at Jabbar’s home in February 1994, the Prime Minister conveyed her regrets and ensured the required security.

It was at about this time that Javed Jabbar was handpicked by Admiral Nayyar, the moving force behind the Neemrana dialogue, the 1.5 Track (not Track II as the respective governments have a hand in choosing the representatives, pay for their travel and are then briefed on the outcome), to be given a Top-Secret message from the Indian Prime Minster, PV Narasimha Rao, to enquire from Bhutto whether she would be prepared to enter into backchannel discussions with India. I have the feeling Jabbar would have quite liked to be the Pakistani interlocutor—and again, in my view, would have been an excellent choice both on the Pakistan side and from the Indian point of view, as his credentials as a fierce Pakistani patriot are unassailable and on display as he frequently baits India, but, at the same time, a reasonable human (being a Madras-born intellectual like almost all bright Pakistanis!) with whom we could do business, although only by driving a hard bargain. (For example, “As part of its mindset of denial of reality, India blamed Pakistan for infiltrating jihadi extremists across the LoC”. Really? Who is in denial of reality—Jabbar or the “Pakistan mindset”?).

Benazir Bhutto, when briefed by Jabbar heard him out “non-committally”. The Foreign Office representative’s “eyes indicated a sceptical look”. Nothing came of the initiative under Benazir, but the thread was picked up subsequently by Vajpayee and Nawaz Sharif, and finally, and most constructively, by Musharraf and Manmohan. I would be interested in learning from his volume on Musharraf what Jabbar makes of the ‘four-point formula’ to resolve the J&K issue with neither side losing face, just accepting the reality on the ground, and moving forward in the interests of the people of the erstwhile State.

In early 1996, Jabbar had his first and only encounter with Murtaza Bhutto, Benazir’s estranged brother at the home of a common friend. “As the meal progressed, and the drinks and dinner proceeded to warm up, the historical role of the PPP became the major theme.” Jabbar argued that “sycophancy” and a “sense of infallibility” had overtaken the PPP “even soon after 1970, leading to the catastrophe of 1971”. There was, remembers Jabbar, “pin-drop silence around the table” when Murtaza got up from his place at the head of the table and marched up to Jabbar directly opposite him. But—“instead of delivering a slap or a punch in the jaw…he put his arms around me in a warm affectionate embrace and even kissed me on my right cheek”.

A few months later, Murtaza was assassinated outside his home in Karachi in a dastardly attack in which many believed—with or without tangible proof—that his brother-in-law, Asif Ali Zardari, Benazir Bhutto’s spouse, was implicated.

All this led in August 1996 to Jabbar resigning from the PPP, coincidentally (or otherwise?) a few months before the illegitimate, if not illegal, dismissal of Benazir’s second government of which he was not a part. Two years later, in August 1998, Jabbar co-founded Farooq Leghari’s Millat Party, becoming its secretary-general and then senior vice-president. He then became a minister for a second time in the Caretaker Government after Bhutto’s dismissal that lasted till the next elections a few months later brought in Nawaz Sharif, the one senior politician with whom Jabbar did not enjoy cordial relations. While Javed says he “winced” at allegations of opportunism over his joining the PPP soon after Zia died and being rewarded a few weeks later with a ministerial post, his assumption of so many avatars in political affiliation over the next decade and a half can only be explained in terms of the ever-shifting sands of Pakistan’s politics. We will get to know better when his book on his interactions with Leghari is published. He was then invited by Pervez Musharraf to serve as Adviser on National Affairs and Information & Broadcasting in the government established in October-November 1999 by Pervez Musharraf after his putsch that ousted Nawaz Sharif. But here Jabbar retrieved his reputation for unflinching integrity when he resigned from the post about a year into the assignment, for reasons not disclosed in this volume but perhaps to be awaited in a subsequent volume on his “interactions” with Musharraf.

His involvement with Party politics ended when in 2004 Leghari merged the Millat Party with one of the factions of the Pakistan Muslim League. Jabbar may have ended his “political” career but remains a prominent public figure whose opinions are eagerly sought and whose views are held in high esteem. (It is a pity that so gifted a Pakistani intellectual is unable, despite my and others’ efforts on his behalf, to get this book published in India or even to have this South Asia-wide best seller imported into our country through normal trade channels. It is a symbol of the total malfunction in our relationship with our “distant neighbour”.)

BUT THIS CHAPTER of Jabbar’s life climaxes not with his resigning from the military dictator’s government but in a luncheon meeting a deux in a Damascus restaurant where Benazir Bhutto and Jabbar found each other attending the funeral of Hafez Assad, she in a personal capacity and he as the representative of President Musharraf. There were no recriminations over the past, just a most friendly conversation about the current situation. “It was now about eight months since General Musharraf had assumed power and she saw no sign of an early return to the political process through democratic means and free and fair elections”. Airily dismissing Jabbar’s attempts to find extenuating conditions to justify the unconscionable delay, she said that in the guise of “accountability”, “certain elements in the military such as in the ISI, in cahoots with orthodox and fascist political parties, including religious parties, had adopted the strategy of “personal destruction” (against her and her party leaders)”.

Emphasising that “Pakistan was at present subject to purely military rule”, she expressed her apprehension of “a possible spill-over of the Taliban approach to Islam”, citing the example of “hijackers forcibly land(ing) an Indian airliner at Kandahar to secure the release of a Pakistani cleric like Maulana Masood Azhar and two others in return for freeing Indian hostages”. She goes on to make the telling revelation that Gen. Musharraf, as Director General of Military Operations (DGMO) in 1994-95, had briefed her about “the potentiality of a Kargil operation” that she had refused to authorise. She apprehended that Nawaz Sharif had let Musharraf get away with his cunning. (So, it was not in 1998-99 that Kargil was planned but years earlier!)

The conversation over lunch ended with agreement that Jabbar would convey to the General, Benazir’s willingness to hold a dialogue with the dictator. While Musharraf merely said, “Leave it with me” when Jabbar briefed him, the dialogue was actually held twice in Abu Dhabi in total secrecy in 2007. A few months later, Benazir Bhutto returned to Pakistan and, after surviving an assassination attempt on her life in October, and finally succumbed on December 27th, 2007 to another assassination attempt.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover_Kumbh.jpg)

More Columns

The lament of a blue-suited social media platform Chindu Sreedharan

Pixxel launches India’s first private commercial satellite constellation V Shoba

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita