RECENTLY, DURING OUR horrific and terrifying second wave of Covid-19, one that brought grief to so many of us, I binge-read Japanese locked-room mysteries for a simple reason—to return to the intellectual pleasure of solving a puzzle. A puzzle, I think, induces a sense of detachment from the trauma and poignancy of an untimely death. In these war-like pandemic times, just like readers in the 1920s and ’30s, we too want to read about a fairytale land where murder is committed again and again without anybody getting hurt.

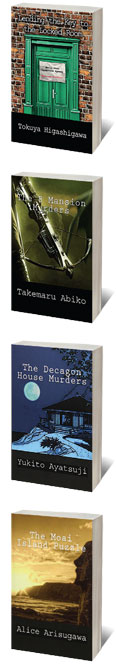

The Decagon House Murders, Lending the Key to the Locked Room, The 8 Mansion Murders and The Moai Island Puzzle (my favourite) follow the path forged by the members of the Detection Club in Britain. Shortly after its founding in 1930, the club members swore an oath that their detectives would “well and truly detect the crimes presented to them without reliance on Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo-Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence or the Act of God.” Logical detection is at the heart of these Japanese mysteries, which bring back the Golden Age flavour.

These writers belong to the Honkaku tradition of mystery writing. Honkaku is “a detective story that mainly focuses on the process of a criminal investigation and values the entertainment derived from pure logical reasoning.” Edogawa Rampo (a pen name which, if one pronounces it fast in Japanese style sounds like Edgar Allen Poe in whose honour it was assumed), a popular writer of fantastical detective stories in the 1920s and ’30s and seen as the father of this movement, decreed that the real scientific spirit was found in this genre.

The 1970s saw a revival among the mystery club members at various universities. The books discussed in this essay belong to that generation of Honkaku writers. They follow the American pre-World War II writer SS Van Dine’s (the pseudonym of art critic Willard Wright) rules of a fair mystery. I have never warmed to Van Dine’s books or his creation Philo Vance, so the Japanese obsession with him was puzzling until I read Japanese mystery writer Soji Shimada’s introduction to the Decagon House Murders. Van Dine is popular with these mystery club members because he proposes the concept of a high degree of logical reasoning as a key prerequisite for detective fiction. Shimada describes Honkaku as a form of the detective story that is not only literary but also, to a greater or lesser extent, a game.

In a locked-room mystery, the focus is not on the motive that led to the crime, or on the psychology of the killer or the social malaise underlying the killer’s actions. The focus is on the howdunnit: how could the victim be murdered in a locked room where he or she was alone?

The writers scrupulously follow Van Dine’s rules. Introduce the suspects who show up on the island or chalet or someplace uninhabited except for the suspects, tell us their profiles, outline the style of the murder, make sure no vital information connected to the deduction is withheld from the reader, and forget about the love stories and other things that detract from the mystery. Oh, and do away with the latest scientific discoveries (for example, DNA, blood group etcetera). Forget the witticisms, the parties and cheery table conversations. Some of them do have humour, characterisation and a picturesque setting, but these are scrupulously subservient to the intellectual interest.

The forerunner of that generation was Yukito Ayatsuji’s The Decagon House Murders. Seven members of a university mystery club arrive at Decagon House on a small island, the site of grisly multiple murders the previous year. Its owner, a brilliant architect, was found murdered along with his wife and a housekeeping couple, while the gardener is missing and presumed to be their killer. The uncle of one of the members has just bought it. The boatman drops them off and is told to return after a week. Now they are the only inhabitants on the island. Thus begins the Japanese version of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None.

These writers belong to the Honkaku tradition of mystery writing. Honkaku is a detective story that mainly focuses on the process of a criminal investigation and values the entertainment derived from pure logical reasoning

Share this on

Each member answers to a pseudonym of a famous Golden Age writer—Agatha, Orczy, Ellery, Carr, Van Dine, Poe and Leroux. To their horror on waking up the next morning, the dining table in the central room of the decagon has seven milky white plastic plates labelled in red letters—the first victim, second victim, third victim, fourth victim, the last victim, the detective and the murderer. Meanwhile on the mainland, two former members of the mystery club get letters saying, “My daughter Chiori was murdered by all of you.” The previous year Chiori died after a mystery club party where she had been forced to drink a lot of alcohol. As the race begins to figure out the connection between Chiori and Decagon House, the bodies pile up on the island. Nailbiting suspense ends in a denouement that is clever and surprising. Ayatsuji plays by Van Dine’s rules in a cheeky fashion in this atmospheric mystery where the turbulent sea comes into its own as a character.

Though Honkaku emerged to challenge the social realism emphasis of mystery writing, some do display the subtle class distinctions of Japanese society, and the passions of past loves, angry in-laws, distant mothers and competitive siblings. In The Moai Island Puzzle, author Alice Arisugawa (a pen name of a man) does a great job in blending these elements with a treasure hunt. Here too the protagonist (also called Alice) travels to an island retreat owned by his fellow mystery club (Maria Arima) member’s uncle. Along with a third member, they embark on a treasure hunt. Maria’s grandfather has left a fortune in diamonds along with a puzzle-map to find it. Three years ago her cousin came close but drowned the day after he told her he was about to discover it. The students join a summer house party with an assorted set of characters and relationships—a painter who lives in the only other house on the island, the grieving fiancé, the truculent younger son, the patriarch and his brother, the brother’s daughter who is deeply in love with her businessman-husband from a lower class, a doctor-friend, and another couple. The light-hearted treasure hunt soon turns deadly as the trio figure out the link between the Moai statues on the island and the treasure. A typhoon warning keeps many of the guests awake. The next morning, two of the house party are found dead, shot in a room that is bolted from inside. Then another murder takes place. The solution, if you follow the clues logically, is not difficult. The charm is in the youthful exuberance of the narrator and the way it blends a picturesque setting with the themes of friendship, rivalry, and loss.

The 8 Mansion Murders, by Takemaru Abiko, on the other hand, is a straightforward puzzle with little analysis of motive or of the killer’s psyche. This one hews to the classic Van Dine formula of a howdunit. Here too, the house is constructed in such a way that the rooms face the area where the murder occurs. Someone shoots an arrow at the victim, and the murder is witnessed by the victim’s deaf and mute daughter and her sign language teacher. The main suspect is the housekeeper’s son to whom the crossbow belongs, and from whose window the witnesses think the shot was taken. He, however, says it was stolen from him the previous week. A bumbling detective is called in along with an assistant/sidekick. In vintage Christie style, diagrams are sketched for the reader and the detective who must figure out the howdunnit to catch the killer. We learn very little about the victim and his relationships, and the killer’s motive is not evident. The solution is clever and simple once we figure out the diagrams.

A Honkaku story can be drawn as a maze. The obstacles before the detectives throw up dead ends. Each setback reveals a characteristic of the murderer’s story or the main hypothesis. ‘Not this, not this’ brings us closer to ‘this’.

Nowhere is this maze-like game more evident than in Lending the Key to the Locked Room where the author, Tokuya Higashigawa, stops at one point and challenges the reader to tell him the solution. I did solve the howdunnit but not the motive, which was less obvious to me.

Film student Ryuhei Tomura knows he would have to find a normal job like everyone else. He has a connection (these jobs materialise only through contacts) in a senior, Kosaku Moro, who promises him a job in the company he works in. Our hero is over the moon, but his girlfriend promptly dumps him for having no ambition. During a drunken binge with his friends, Tomura publicly threatens to kill her. Then she turns up dead, stabbed and thrown from her balcony, just when he is in Moro’s flat, watching a video in a swanky soundproof movie theatre room. Moro’s flat is a two-minute walk from the girlfriend’s flat. Worse still, Moro, who could have given Tomura an alibi, goes to have a shower and doesn’t return. After a while our hero goes to check and finds Moro dead, stabbed in his side with a knife, the same one used on the girlfriend. The apartment is bolted from inside, leaving our hero as the main suspect. In a panic, he runs to his brother-in-law, a Philip Marlowe-type private investigator who launches a parallel investigation. Here too, humour threads through the scenes when the police detective duo on the hunt for our hero keep missing the private eye duo. This is an affectionate and humorous pastiche on the mores of a locked-room mystery.

About The Author

Shylashri Shankar is the author of Turmeric Nation - A Passage Through India's Tastes

More Columns

On Being Young Surya San

Why Are Children Still Dying of Rabies in India? V Shoba

India holds the upper hand as hostilities with Pakistan end Rajeev Deshpande