A Portrait of Death and How to Face It

A meditation on death in the time of viral fear

/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Death1a.jpg)

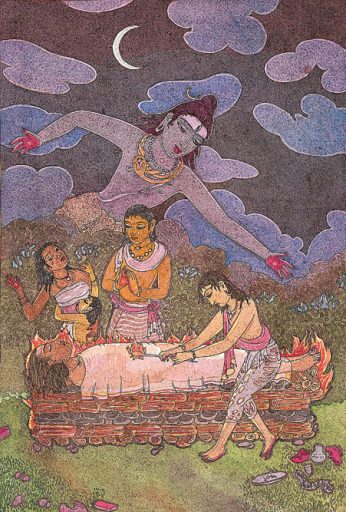

A painting by S Rajam depicting Shiva offering His blessings at a funeral (Photo: Alamy)

ONLY ATHEISTS BELIEVE IN DEATH. Theists belong to infinity. For them, a funeral is merely transition of the atman, rooh or soul from one manifestation to another; from existence on earth to a new natural beyond life.

God is synonymous with life, not death. In every religion an eternal God has promised eternity to his human creation. During the mortal phase of life, God is one dimension away from even the most faithful of believers, but in the hereafter the Almighty becomes an omnipotent executive presiding over whichever dwelling has been earned by the individual.

Clearly the spirit, once released from human bondage, finds a far more democratic ethos. There is no distinction of social, financial or political rank in heaven, or indeed hell. The only king or caliph in the Abrahamic faiths is God, Allah or Jehovah. In Hinduism, divinity becomes plural, but the human being cannot rise beyond the semi-divine. In Hinduism and Christianity, God can become man; man cannot become God. In Islam, the doctrine of tauhid—and its equivalent in Judaism—makes God unitary and indivisible.

The origins of Hinduism lie in the Vedas. The Rig Veda, an anthology of 1,028 Sanskrit hymns originating in the Indus Valley Civilisation that flourished some 4,000 years ago, is surely among the most profound, nuanced and stimulating enquiries into the fundamental mysteries of creation, life, death and divinity, a bridge between duty and destiny, time and infinity, experience and morality, individual and universe. It is a philosophy where death is a sadness, without terror.

In the Vedic beginning, there was neither existence nor non-existence, ‘neither death nor immortality’ [I have used the translation by Wendy Doniger, published by Penguin]; even the gods came after creation by an original progenitor, called Ka and then Prajapati, who later created man. Rita, the cosmic order, and satya, truth, were born from tapas, the heat of sacrifice.

Yama, elder son of the sun, was the first man to die. He became, thereby, pathfinder to the afterlife, as well as our collective creditor: every mortal is in his debt by virtue of birth. A hymn asks us to honour ‘King Yama’, son of Vivaswan, with soma and oblation rich in butter and honey, for ‘Yama was the first to find a way for us’; his two four-eyed dogs may thirst for ‘the breath of life’ but they still lead us to heaven. [It was only in later traditions that Yama was re-imagined as a demon.]

‘Go forth,’ says a hymn to the dead, ‘go forth on those ancient paths on which our ancient fathers passed beyond. There you shall see the two kings, Yama and Varuna, rejoicing in the sacrificial drink’ [the Svadha, or Soma; the sacrificial call is Svaha]. The next verse is an exhortation: ‘Unite with the fathers, with Yama, with the rewards of your sacrifices and good deeds, in the highest heaven. Leaving behind all imperfections, go back home again; merge with a glorious body.’ And so, not only do the dead get a new life but they also get a glorious body to replace the one that was incarcerated. Death is a return, not a departure.

The Burial Hymn is even celebratory: ‘Go away, death, by another path that is your own, different from the road of the gods…Those who are alive have now parted from those who are dead. Our invitation to the gods has become auspicious today. We have gone forward to dance and laugh, stretching farther our own lengthening span of life’. Soma, the plant of heaven, induces both ecstasy and immortality.

THE FUNERAL CHANT in Islam is a verse from the Quran: Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji’oon (From Allah we come, to Allah we go). Death is an episodic fact in Islam, a necessary prelude to the judgment day whence begins the eternal existence in the cosmography of heaven and hell: there are traditionally seven heavens but only one hell. This life is a mere probation, for ‘Every soul shall have a taste of death; and only on judgment day shall you be paid your full recompense. Only he who is saved far from the fire and admitted to the garden will have attained the object [of life]. For the life of this world is but goods and chattels of deception’ [Surah 3:185]. Allah tells mankind: ‘We have decreed death to be your common lot, and we are not to be frustrated from changing your forms and creating you [again] in [forms] that you know not’ [Surah 56: 60, 61; from the translation by Abdullah Yusuf Ali].

There are graphic descriptions of heaven and hell in the Quran; see Surah 76, among others. Heaven, the eternal home for those who have pleased Allah, is a garden of bliss, with fountains, mansions, rivers, fruits, carpets, chaste companions, abundance, joy and tasnim, a drink superior to the purest wine. There is no vain discourse, and therefore peace and security. There is no envy, worry, toil, sorrow.

Hell, in contrast, is the abode of arrogance for those who dismissed religion as an amusement. Their fate is to drink boiling, fetid water, burn in a furious fire and plead for an end that will never come. At the bottom of hell grows the cursed and pungent tree of Zaqqum, as bitter as the food. There is much more. The point, of course, is that it is up to the human being to choose his or her destiny in the next life. ‘Lost indeed are they who treat it as a falsehood that they must meet Allah—until on a sudden the hour is on them, and they say: ‘Ah! woe unto us that we took no thought of it’, for they bear their burdens on their backs, and evil indeed are the burdens that they bear’ [Surah 6:31].

There is no confusion in the relationship between this life and the next. As the powerful Surah on qiyamah, or resurrection, puts it: man will be evidence against himself.

Death is an episodic fact in Islam, a necessary prelude to the Judgment Day whence begins the eternal existence in the cosmography of heaven and hell: There are traditionally seven heavens but only one hell. This life is a mere probation

The search for this evidence is constant; two guardian angels, one sitting to the right and the other to the left note every word spoken. According to tradition, the angels are called Munkar and Nakir [although they are not so named in the Quran]. The first question after death is about the deceased’s conviction in Allah and His Prophet: if the answer is correct there is a pleasant wait till Paradise. This quiescent state is known as barzakh, when the deceased wait till judgment or ‘till the day they are raised up’ [Surah 23:100].

Perhaps the most powerful passage in the Quran about life and death is in Surah 50, Qaf, which contains the famous verse that Sufis cite to claim proximity to Allah: ‘It was We who created man, and We know what dark suggestions his soul makes to him, for We are nearer to him than [his] jugular vein’. Verse 19 says: ‘And the stupor of death will bring truth’. Abdullah Yusuf Ali explains that the ‘stupor or unconsciousness to this probationary life will be the opening of the eyes to the spiritual world for death is the gateway between the two’. Your destination will be determined when the trumpet of judgment is blown and an angel will drive each soul to bear witness. There is no escape from judgment: ‘The word changes not before Me, and I do not the least injustice to My servants’ [Surah 50:29].

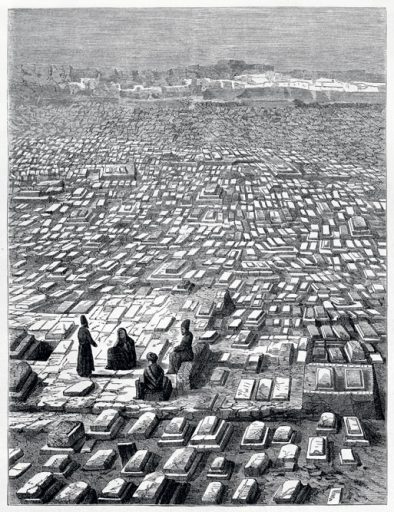

The Persians have a term for death: Shahr-e-Khamoshiyan [City of Silence]. Allah breaks that silence with justice.

In his first letter to the Corinthians, the apostle-intellectual Paul dwells at length on the ultimate existentialist question, the mystery of death. He is challenging the ancient exoneration of excess, and its inherent sins, encapsulated in the aphorism that remains a familiar call: ‘Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.’

Paul answers: ‘Lo! I tell you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. For this perishable nature must put on the imperishable, and this mortal nature must put on immortality. When the perishable puts on the imperishable, and the mortal puts on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written: ‘Death is swallowed up in victory’.’

This is followed by the much-quoted lines: ‘O death, where is thy victory? O death, where is thy sting?’

There is eternal repose in heaven, a promise abundant through both the Old and New Testaments. In his second letter, St Peter tells the faithful to ‘wait for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells’ echoing the revelation of the apocalypse to St John: ‘Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband; and I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ‘Behold, the dwelling of God is with men. He will dwell with them, and they shall be His people, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning nor crying nor pain any more, for the former things have passed away.’

Clearly, something to look forward to after an earthly life filled with misery, poverty, anxiety.

The Rig Veda is surely among the most profound, nuanced and stimulating enquiries into the fundamental mysteries of creation, life, death and divinity. It is a philosophy where death is a sadness, without terror

The God of the Bible is, in essence, precisely the same as the Almighty of all faiths: ‘I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end’. Alpha is genesis, when heaven and earth were the first in the sequence of creation; and in the end is liberation, the return from earth to ‘Our Father, who art in heaven’.

As the Bible puts it, the last enemy to be destroyed is death.

SO WHAT THEN of science, the buttress and rationale of those who dismiss God as a myth, a prop for the intellectually weak and perennially frightened? Science uses evidence and enquiry as the basis for a doctrine like the big bang theory of creation, which postulates that the universe began with a ‘primeval atom’ some 14 billion years ago, and sneers at those who accept truth as the mysterious outpouring from a mysterious, invisible, unfathomable eternal being installed in the sky.

Let us set aside the temptation to treat the religious model as a metaphor for the scientific; or suggest that 14 billion years in the latest chapter of scientific chronology and a day in Genesis are merely different interpretations of our still evolving notions of time. This will merely displease votaries of both groups and persuade neither. But a book I have been reading sparked a counterintuitive question: Does the advance of science confirm that creation was a miracle?

Let us look at the product for a moment rather than the producer.

The author Bill Bryson erupted into the publishing universe as a big-bang travel writer, but has now emerged through a form of Darwinian literary evolution as a popular chronicler of serious science, with the unique ability to enliven facts with a gentle sense of humour. Here are a very few, randomly cherry-picked facts from his densely packed book with a self-explanatory title, The Body:

*Every day we breathe about 20,000 times, processing an average of 12,500 litres of air, taking over seven million breaths each year. Each time we breathe, we exhale 25 sextillion molecules of oxygen [even the thought of such a number is exhausting];

*In an urban environment, a person can inhale some 20 billion foreign particles each day including dust, pollutants, which are then cleaned out by our lungs or diverted by many millions of cilia to the stomach where they are dissolved by hydrochloric acid;

*The eye can distinguish between two and 7.5 million colours, and darts on an average of four times every second;

*Each person produces between five to ten ounces of tears every day which are drained through tiny holes known as puncta; the tears we see are an overflow during spasms of high emotion;

*We can detect up to a trillion odours [I still find it hard to believe that there are so many odours, but there you are];

*The heart beats more than 3.5 billion times during a normal lifespan;

*Every day the heart, which weighs less than a pound, dispenses 6,240 litres of blood;

*Nerve signals travel at 270 mph.

*Why don’t people get mumps twice? Because the body contains T-cells with a memory of previous invasions by pathogens, and create adaptive immunity even after six or seven decades. That is why many diseases attack only once;

*Sneeze droplets [the latest weapon of mass destruction] can travel a distance of eight metres, drifting in suspension like a sheet for up to ten minutes;

*Around 75 per cent of the brain is water, the rest fat and protein. Living in dark silence, the brain churns more information in 30 seconds than the Hubble Space Telescope can process in 30 years;

*One cubic millimetre of brain, equivalent to about grain of sand, can hold information equivalent to a billion copies of Bryson’s book. An average brain has the capacity to contain the entire digital content of the world, as measured in 2019 [when The Body was published].

Let’s not even go near neurons, or gape at the notion that the eyes send a hundred billion signals to the brain every second. My question is: could all this incredible machinery happen by sheer accident?

You have a signature brain. You be the judge.

Click here to read all Coronavirus related articles

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande