November 1956. Landing of the Granma! This 60-foot diesel-powered vessel was built in 1943 by Wheeler Shipbuilding of Brooklyn, New York. It was a light-armoured target practice boat. The name “Granma” (grandmother) was endearing and affectionate, and it went on to secure its place in world history. How? Granma carried 82 fighters from Mexico to Cuba who were determined to overthrow the US-imperialism-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista. And they did. The 82 expeditioners-rebels included Fidel and Raúl Castro, Ernesto Guevara, Juan Almeida Bosque, and others.

Three years prior, in 1953, when Fidel was captured after the Moncada attacks in July, he spoke for nearly four hours, defending his revolutionary actions. He ended his speech with, “Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me.” But did history absolve these men only because their revolution succeeded later? Or is the act of rebellion itself, even though a failure, enough? We will return to it.

Forgetting is a quiet race against remembrance. In the last few years, with the official patronage, the figure of the “forgotten hero” is back. The politics of remembrance understate the inherent tensions between history and memory. When do we realise that we have forgotten someone, or some event? One of the barometers in recent discourse is how much space is provided to an individual in official knowledge sites, or emblematic acts of the state power. So, while Mahatma Gandhi on every currency note in India is almost impossible to forget, the same cannot be said about Baba Sohan Singh Bhakna. Kartar Singh Sarabha is well-known merely as Bhagat Singh’s inspiration, as if his life cannot have its standing. These examples in Indian history could be multiplied by thousands.

To make things more difficult, as Benedetto Croce reminded us, “All history is contemporary history.” History is considered contemporary when it is interwoven with life in a tangible manner, rather than abstractly. It achieves this by maintaining a connection while simultaneously distinguishing itself from life. Think about our world today. Growing racism. Rising walls on the borders that disfavour immigration. Nationalism is becoming uncritical and xenophobic. Identities are getting weaponised. And a relentless pursuit of changing all this persists. When we sit out to write histories of these developments, we are with contemporary at our best. That’s when Rana Preet Gill shines with brilliance.

Making of the Book

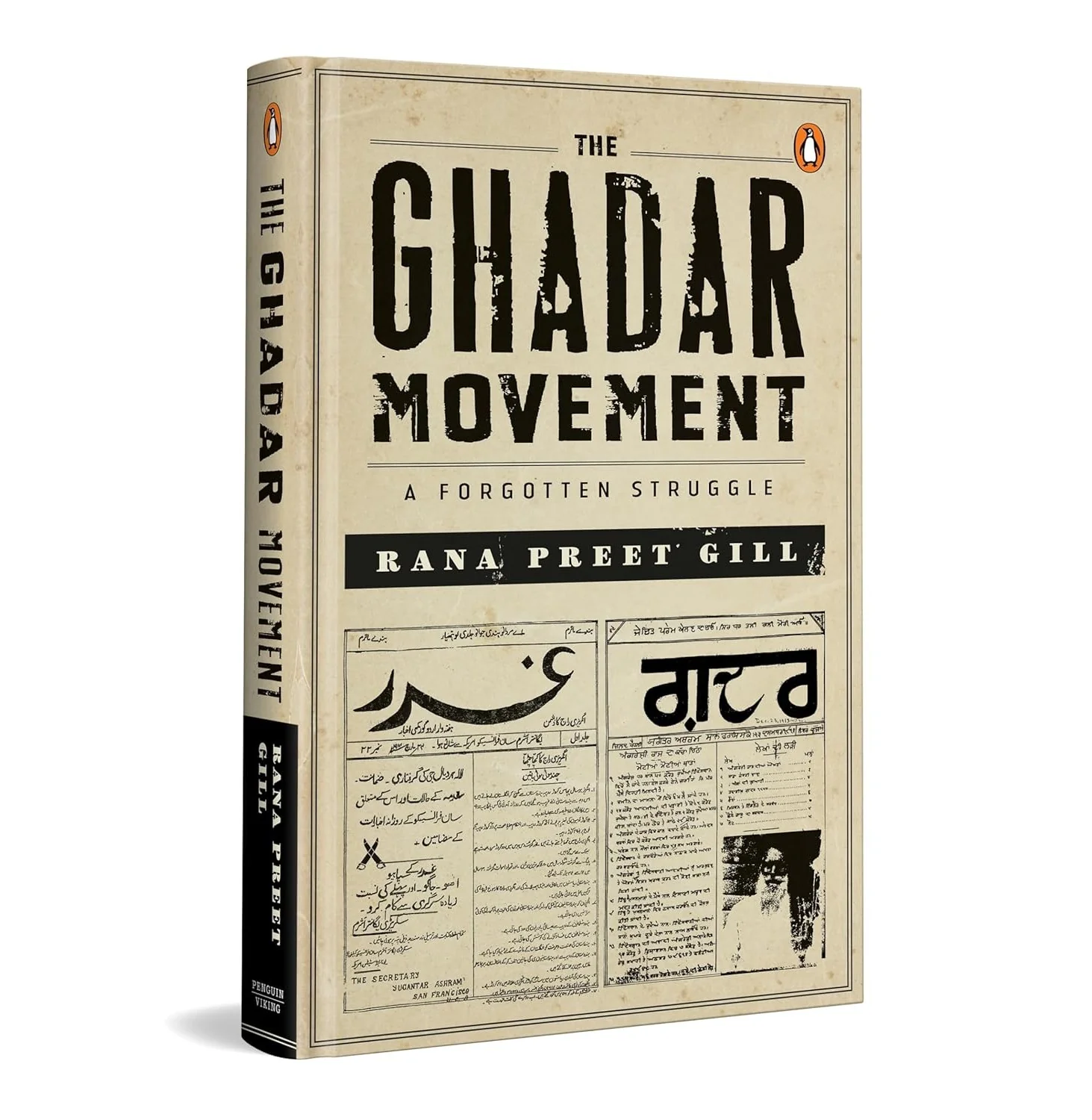

Rana Preet Gill, a Veterinary Officer with the Punjab Government and a novelist, has chosen to don another hat. She has come to us as a public historian. No, not the usual professional historian who actively engages with the public and applies their historical knowledge. She is a “non-professional” who thought it was crucial to write a readable and accessible history of the Ghadar Party and the movement it became.

The author’s endeavour started with a visit to the Andamans, where she discovered the statue of Pandit Ram Rakha Bali at the Cellular Jail. She candidly confesses that even though she had been a resident of Hoshiyarpur (Punjab) for almost a decade, she knew nothing of Bali, who was from the town. Bali was sentenced to life and transported to the Cellular Jail in the Mandalay Conspiracy Case. Ram Rakha resisted the jail authorities through a hunger strike. He fasted for three months before dying in 1919. An honest reader would concede they weren’t aware of these details. Many of such details evade us. They are not a part of public memory. They could merely be looked up in obscure books in libraries or sometimes in half-enthusiastic Google searches.

Gill enters the book as a coming-of-age story. She narrates how she embarked on the journey to know more about the Ghadar party and its moment in history. Having read academic works of like Harish Puri, she realised how less was written, and how more could be done. She is right. The last accessible book on Ghadar was written by Harish Puri in 2011 by the National Book Trust.

Gill’s book runs in 38 short chapters. Well-woven with subheadings. Many lesser-known individuals have been made to come alive. The last two chapters sum up the legacy and continuities of Ghadar after 1918. Three informative annexures list out what became of those who fought, the role of women, and the legacy of Ghadar. The book reads like a fast-paced thriller. A page-turner. Easy. Candid. Informative. Unpretentious.

Moving out of India

The author sets off with the making of revolutionary fervour in the initial chapters. A helicopter view of Bombay, Bengal and Punjab under British rule has been undertaken. Next, the emigration of the Punjab peasantry has been discussed in detail. Among these people, the likes of Sohan Singh Bhakna and Pandit Kanshi Ram, who sought fortunes in the US and Canada, later became important figures in the Ghadar Movement.

The author identifies her subjects based on their social and economic mobilisations too. Ram Rakha Bali, Harnam Singh Sahri and Harnam Singh Tundilat joined the army and police to better their chances. A few like Kartar Singh Sarabha, DarisiChenchiah, Jatindra Nath Lahiri and Vishnu Ganesh Pingle went out of British India to study with better opportunities. Then there were revolutionaries in exile or otherwise who had assembled in cities like London and Berlin. Many names are well-known and need not be reproduced here. Lala Har Dayal and others join the narrative soon.

Even though the author doesn’t name it explicitly, what she does throughout the book by way of method is called prosopography. The method’s principle is simple: Defining a population based on one or several criteria. Designing a relevant biographical questionnaire that includes a variety of variables or criteria. Describing those variables in terms of social, public, private, and/or cultural, ideological, or political dynamics.

In the process of listing out people by their names and compiling their short biographies, the author has her method. She delves into the personal histories and journeys of many emigrants. Thus, teasing out insights into their lives and struggles. The first step towards contemporary history. The walls on the borders grow taller and stronger today. There is a new wave of racism in Canada and USA, despite the modern sensitivities of inclusivity and diversity. Why not go back to those who shared the same fate in a different historical landscape?

The Call of Ghadar

The author narrates how the Canadian government, in the early 20th century, wanted to close its doors to Indians. It was no secret. The genesis and politics of the Indian Emigration Act (XXI of 1883) and thereabouts have been explained well. Little details like how, after getting a go-ahead from the British government, the Canadian government raised the amount of money that an immigrant had to have on arrival to $200 from $25.7 ring so relatable today. We are also told how Punjabi immigration to the US was a spillover from Canada, and from 1904 to 1906, about 600 Indians had crossed over. The number of immigrants in the US increased from 1072 in 1907 to 1710 in 1908.

Naturally, with people united in their struggle, politics of association germinated. The author argues that the awakening of political consciousness in Indians residing in Canada and the US was the result of three factors. Resentment and hostility towards the white community for its prejudice and oppression led to the development of an ethnic identity, which in turn fueled nationalism directed against British colonialism in India.

In this moment, Ghadar was born. The author beautifully writes, “Ghadar was not only a weekly newspaper; it soon became a cause, and they used it to exhort those still in deep slumber.”

The rest of the book is about the programme, participants, reach, impact, expansion, and the actions of Ghadar. In instalments, the reader will encounter different stories inspiring varied emotions. Tale of Komagata Maru. How hundreds of Ghadarites returned to India to incite rebellion and coordinate with underground revolutionaries. Hindu-German Conspiracy. Lahore Conspiracy. And so on.

The book makes it a point to document the lives and activities of many Ghadarites after 1918. This provides a sense of continuity to the people and their thoughts. Drifting away from the conventional viewpoint in which Ghadarites only live on as an inspiration for the next generation of more popular revolutionaries, the book documents the facts.

For instance, in the Andamans, a strike was started by the Ghadarites in support of a prisoner named Gujarati Mal, confined to solitary confinement for six months along with fetters. Mal had retorted when he was subjected to racial abuse. Eight Ghadarites attained martyrdom in the Andamans: Pandit Ram Rakha, Bhan Singh Sunet, Rulia Singh Sarabha, Kehar Singh Marhana, Roda Singh Rode, Swar Natha Singh Dhotian, Nand Singh and Surain Singh. These names and their deeds, the act of retrieving them, is what history is supposed to do. Whether it always does so is deeply contestable.

Few Critical Departures

Gill’s retrieval of “forgotten heroes” makes them accessible to the people. But will the act also make them regain their rightful place in the emblems of official knowledge? Can we imagine a future, or do we know of a past, when we have/had a respectable descriptive account of the ideologies of the Ghadar Movement in state-published textbooks?

To answer those questions, it is crucial to appreciate the power of narratives. Facts exist without us even knowing them. That’s why they are retrieved. Interpretations, on the other hand, are (re)constructed. They are the barrels through which political power grows. Think of someone like Baba Sohan Singh Bhakna, a synonym of the Ghadar Movement. Babaji lived till December 20, 1968, going to the gallows even after independence. His closeness to the Communist Party of India (CPI) is well-known, and so was his association with the Kisan Sabha Movement.

Babaji’s hunchback was the stamp of Congress rule after independence. He writes: “In 1948, I was arrested along with Comrade Sohan Singh Josh and seven or eight other comrades. There was no solid reason. Administration in the Yole jail was worse than the British times. We had to resort to hunger strike. That hunger strike in old age was most difficult. Illegal confinement and hunger strike in Yole camp deformed my backbone. Now whenever one asks me, I reply that this is the stamp of national government of my back.”

Think of Bhakna’s ‘Last Testament’. On 27 November 1968, hospitalised, he asked his comrades to take dictation. Among other things, he said, “I am very thankful to those comrades who gave me a knowledge of Marxism through study circles and discussions and armed me with this ideology. I am diametrically opposed to Gandhism, as it has failed to solve the problems facing the country.” The testament was published in Nawan Zamana on November 27, 1968.

Ghadar Movement’s banner of anti-imperialism and their sacrifices was aloft everywhere. They were in the Akali movement, Congress and socialist movement, Naujawan Bharat Sabha and the worker-peasant upsurge. How were they reduced to provincialism when they should’ve been fundamental to an inclusive nationalism or the idea of India?

Making more use of the accounts of Sohan Singh Josh, who wrote about Ghadar from a wider perspective, would have made Gill’s narrative fiercer. More interpretative. More controversial.It is worth asking why CPI carried on with the legacy of Ghadarities while successive national regimes chose to forget them. Why are there more books on Ghadar revolutionaries from People’s Publishing House (Delhi) than Govt of India’s Publication Division or the National Book Trust?

Gill’s account of the Ghadar Movement is the best in recent times. It evades the officialdom of previous publications. The book leaves us with many details that could be shaped as questions by an alert reader. An informed reader must ask why certain individuals are only remembered in specific historical contexts, when they lived in and were part of many others. Gill pushes us to recall Ghadar beyond its one-party and one-movement perspective. It is for the readers to appreciate her zeal and cheer for her belonging. By retelling the story of a movement, she has appraised some of the global issues that stare us today.

About The Author

Shaan Kashyap is a PhD candidate at Ravenshaw University, Cuttack. Currently, he is Sir Jadunath Sarkar Fellow for Indian History (2024-25)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/ghadar-ranapreet.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Travel-Issue-2025.jpg)

More Columns

The Modi engine continues to steamroll 11 years on Open

Vizhinjam makes history as world’s largest container ship docks in South Asia Open

Israel Detains Greta Thunberg Open