A Healing Touch

The notification of the Citizenship Amendment Act rules is a significant milestone for the Modi government’s core agenda that will play an important role in BJP’S election campaign as the party sharpens its nationalist credentials

Rajeev Deshpande

Rajeev Deshpande

Rajeev Deshpande

Rajeev Deshpande

|

15 Mar, 2024

|

15 Mar, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/CAA1.jpg)

Hindu refugees from Pakistan At A Camp In New Delhi, March 13, 2024 (Photo: Ashish Sharma)

HINDU SINGH SODHA CAME TO INDIA WITH HIS FAMILY AS A 15-year-old in 1971. Though young, the teenager retained clear memories of his family’s dislocation and the circumstances that set them on a journey that millions undertook in 1947. Sodha studied on a fellowship and after a spell of student activism, gravitated towards a cause that became a lifelong mission. Sodha’s espousal of the rights of Hindu and other minorities from Pakistan led to the formation of the Pak Visthapit Sangh (PVS, Displaced Pakistanis’ Organisation) in 1999 that became Universal Just Action Society (UJAS), a registered NGO. The notification of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) rules on March 11 was a landmark event for Sodha who recalled the days when he had trouble convincing officials about the plight of refugees. “I have welcomed the development. There was a time when I was asked, ‘Which Pakistanis are you talking about? Are there not enough unemployed and poor people in India?’” Sodha tells Open. After working with people who have followed in the footsteps of his family for over three decades, Sodha feels a sense of satisfaction even as niggles in paperwork may still need to be sorted out.

For Hindus who left Pakistan and arrived at the border crossing points like Munabao in Rajasthan, the moment has marked the beginning of another struggle, almost as daunting as the lives they left behind. They were no longer subject to the arbitrary impositions of a blasphemy law or the horror of abductions, forcible conversions and marriages of minor girls never seen again by their families. But the struggle for a new identity was laced with unending challenges. Having arrived in India, often on visas intended to facilitate pilgrimage, they had cut off the option of returning to Pakistan. While getting hold of documentation to enable employment or schooling was difficult, they ran the risk of becoming ‘illegal migrants’ once the validity of their documents expired. It was a cruel cut after the privations that had forced them to leave the land of their forefathers. Occasionally, considerate district officials roped in NGOs to help informally school children and turned community halls into shelters. Most refugees who crossed into India eked out livelihoods as daily labourers, depending on acts of charity or the support of sympathetic activists. It is a telling indictment of the conditions they had fled that, despite the prolonged uncertainties that loomed ahead, very few considered returning to their old lives.

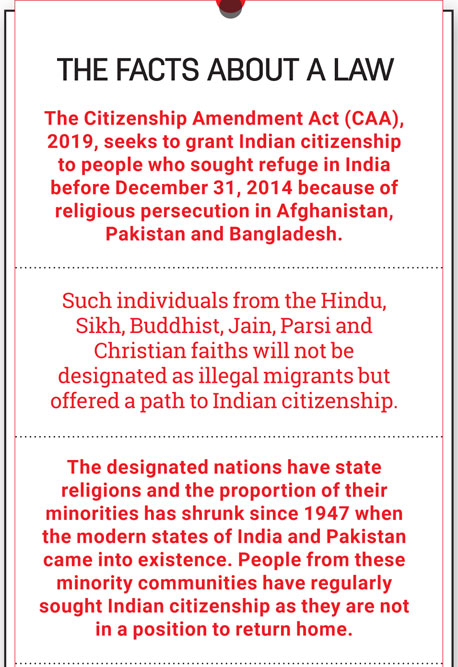

In a well-reported case in 2016, it required then External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj’s intervention to ensure that a young Hindu refugee from Pakistan gained admission in a school which had been denied due to the lack of documents. This was hardly an isolated case and more than one student approached Swaraj for succour. It was only by way of notifications dated September 7, 2015 and July 18, 2016 that such migrants and their families were finally made exempt from the adverse penal consequences of the Passports Act and Foreigners Act. In an order passed in 2016 the Centre made such persons eligible for long-stay visas to prevent them from being declared illegals or being subject to deportation proceedings. The hardships of Hindus and other minorities fleeing Pakistan were accorded priority by the first Modi government even as the process of amending the 1955 citizenship law was under consideration. With many refugees unable to produce documents that were either lost or left behind, leaving them with no option but to apply for citizenship through naturalisation, the period of residence in India has been reduced from 11 to five years. The CAA legislation, passed by Parliament on December 11, 2019, recognised that people of minority communities—identified as Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians, Jains, and Buddhists—who came to India due to religious persecution needed a special regime. The law reflects the view that India has a historical responsibility towards people from these religious groups who were caught on the wrong side of history and paid a heavy price for their misfortune, becoming more and more disadvantaged in the land of their birth.

The notification of the CAA rules and the first applicants who will get Indian citizenship will figure prominently in BJP’S campaign as the party leverages Narendra Modi’s ‘nation first’ policies

“There is little doubt that the reason why Hindus leave Pakistan is due to religious oppression and discrimination. They find that they will continue to face hardship unless they change their religion. It speaks of their determination to hang onto their roots that they leave their ancestral homes and come here. Pakistani officials know they won’t come back and do nothing to stop them from leaving,” Sodha says.

The new rules have removed major hurdles like the renewal of passports that had become a tool of extortion with the Pakistan High Commission charging high fees. Sodha points out that the reduction of residence in India from 11 to five years was welcome as it cut the wait for people bereft of a country. There are issues that might come up during the application process that Sodha feels can be sorted out by the empowered committees in every state and Union territory.

The historical and cultural dimensions of CAA are most apparent in states that were most impacted by Partition. West Bengal continued to experience the tremors well after the creation of India and Pakistan, with a massive influx of refugees in the lead-up to the 1971 war and thereafter as well, particularly under the regime of Khaleda Zia in Bangladesh. BJP candidate for Jadavpur, Anirban Ganguly, points to the emotional and cultural significance of allowing Hindus displaced from Bangladesh to gain Indian citizenship. “A large number of Hindus kept arriving in India and they needed to be given legal rights,” he tells Open. Soft-spoken and well-read, Ganguly comes across more as an academic than a politician and acknowledges that contesting elections is a challenge. As head of the Syama Prasad Mookerjee Foundation, Ganguly is well-versed with the historical context of migration into India. “There are migrants with an India connection who require protection as they have lost their homes. When BJP’s opponents speak about ‘detention centres’, they are appealing to a vote bank that left Bangladesh due to a ‘pull’ factor, not a ‘push’ factor,” says Ganguly. He feels CAA will be welcomed by all communities who had to leave Bangladesh. “There is no resentment against them. Their case is seen as deserving,” he adds.

The condition of Hindus in East Pakistan was no better than that in the western wing after Partition. They were subjected to brutal communal violence ahead of and during the division of India into two nations. Reports of the Noakhali violence provide a grim record of savagery. A relief team that reached the area in early November, 1946, about a month after the anti-Hindu rioting began, saw despair and hopelessness everywhere. They recorded the plight of hundreds of women who had been sexually assaulted and forced to marry the murderers of their husbands and sons. Thousands were forced to convert to Islam, made to eat beef and recite religious texts. The active participation of Muslim League supporters in the violence was a precursor to what Hindus and Buddhist communities like the Chakmas would suffer in East Pakistan and later in Bangladesh as well. In its October 1946 reports, the Amrita Bazar Patrika said death was staring in the face for residents of dozens of villages and The Statesman reported that thousands had been left to the mercy of riotous mobs that looted, burnt and killed with impunity as the district administration and police watched on.

The conditions of Hindus deteriorated rapidly after Partition as the imposition of the passport rules for travel to India made it all but impossible to leave. Getting the document was expensive and time consuming, and Hindus seeking sanctuary across the border found themselves trapped in East Pakistan. Speaking in Lok Sabha on November 15, 1952, Bharatiya Jana Sangh founder SP Mookerjee said Pakistan had “settled” its minorities question in the past five years and stood denuded of its minority population. He was particularly scathing about the pact concluded between Liaquat Ali Khan and Jawaharlal Nehru (the Delhi Pact) in April 1950, saying it had fallen to his lot to oppose the agreement on the grounds that “the very people… responsible for the carnage were being entrusted with the responsibilities of looking after the minorities.” Mookerjee had pointed out that not only the arrival of large groups of refugees but their absence as well could be a reason for concern. “[It is] the policy of squeezing out the minorities, squeezing out, not flooding out. I shall have to refer to this because a point was raised by the minister of rehabilitation the other day that if the policy of the Pakistan authorities is squeezing out its minorities, then why are not more people coming out after passport (rules came into force)? Why should Pakistan prevent the passing out of a larger number of people? But it is squeezing out, not flooding out; because if very large numbers of people come out at one time, then, immediately it produces a reaction in India and naturally it may create a situation which may not be very desirable from the point of view of Pakistan,” Mookerjee observed.

The compilation of Mookerjee’s select speeches and articles by authors and parliamentarians Balraj Madhok, Hiren Mukherjee, Chaudhary Ranbir Singh, and KR Malkani, published by the Lok Sabha Secretariat in June 1990, provides an insightful account into the debates over post-Partition migration and the costly errors in negotiating the safety of minorities in Pakistan or providing for their relocation to India. As Mookerjee had remarked, they had chosen to stay back in West and East Pakistan despite the violence during Partition and the renewed migration showed that powerful reasons were forcing Hindus to leave their homes and hearth.

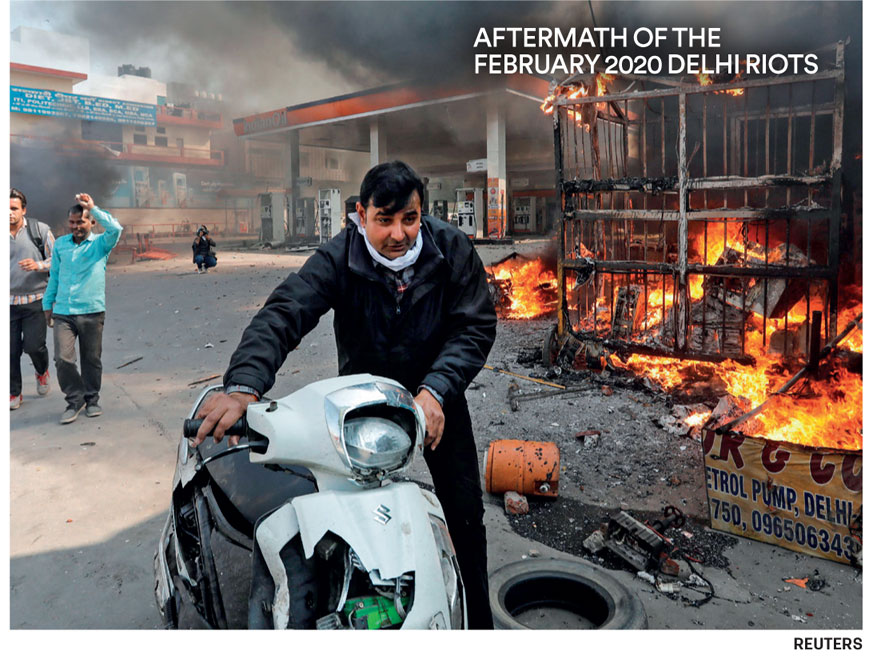

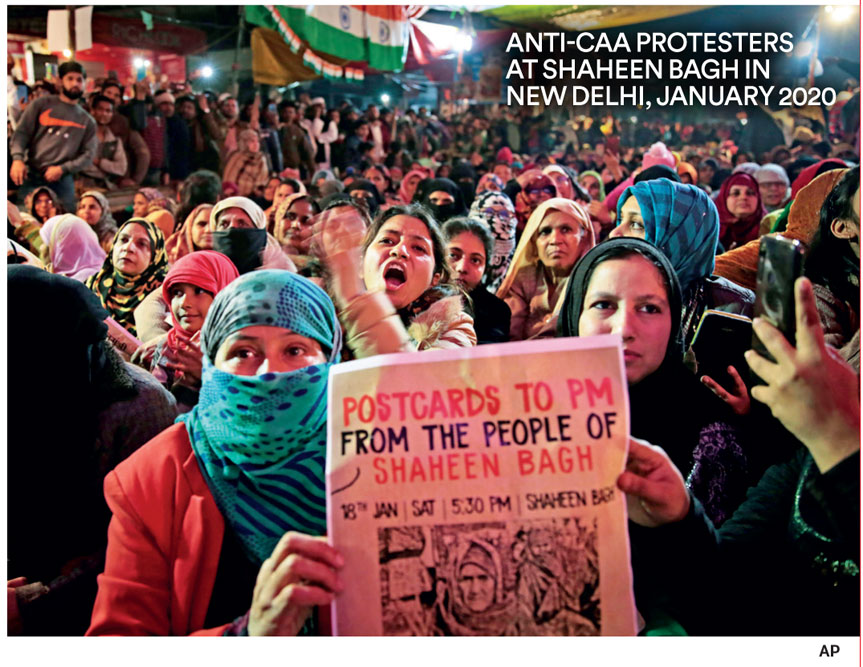

HE PASSAGE OF the CAA Bill in Parliament more than six decades after Mookerjee’s speech was followed by widespread protests from Muslim and Left organisations and sections of civil society. It all had also resulted in rioting. The North East Delhi riots of February 2020, in areas like Jaffrabad, were ostensibly timed to coincide with the visit of then US President Donald Trump and cause international embarrassment for the Modi government. As it turned out, Trump avoided any comment on the riots but the violence extracted a high cost in terms of life and property. It was evident that the riots and earlier protests, such as the one at Jamia Millia Islamia in December 2019, were carefully planned. The use of petrol bombs, bricks, sticks, wet towels and blankets (to smother teargas shells) indicated the violence was not spontaneous. Police investigations were to reveal that concerted efforts were made to inflame opinions, with the chief protagonists organising meetings and delivering provocative speeches in the weeks leading up to the Delhi riots. The locality of Shaheen Bagh became the site of a prolonged sit-in protest, leading to a massive dislocation of traffic and causing a security nightmare with an incident of shooting that saw the offender raising provocative slogans. The anti-CAA protests were fuelled by the contention that the legislation would be followed by a nationwide National Register of Citizens (NRC) aimed at identifying and deporting illegal migrants, and this was read as a move that would potentially target Muslims and strip them of Indian citizenship.

The Centre’s contention that such was not the case did not convince protesters with slogans like “Hum kagaz nahin dikhayenge (We will not show our papers)” reflecting their sentiments. The main accused in the criminal conspiracy to organise the riots are still in jail, finding bail difficult to come by, or are out after lengthy legal processes. Though the cause of the Delhi riots was sought to be pinned on incidents like a pro-CAA rally by BJP leader Kapil Mishra at the Jaffrabad Metro station that was blockaded by nearby residents opposing the law, it is evident that the violence had been curated, right down to distribution of red chilli powder to be thrown at the police and stockpiling of stones. The February 23, 2020 incident at the Metro station, which saw residents stoning the pro-CAA protesters, led to tensions in Welcome Colony, Bhajanpura and Khajuri Khas. The rooftop ‘sling shots’ used to hurl stones, such as the one found by the police on the roof of the residence of AAP leader Tahir Hussain, were more evidence that it was not just one particular incident like the showdown at Jaffrabad Metro station that had led to the riots that resulted in 53 deaths.

Addressing an election rally in Delhi on December 23, 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had said, “[Then] there is the NRC, such lies are being spread. This was considered in the Congress era, we did not make it, it has not come to Parliament, nor in the Cabinet, nor are there rules and regulation, a haua (bogey) is being created and I have already said, in this very session of Parliament where we have legislated on benefits without regard to religion, will we pass another that will expel you? …After my government assumed office, after 2014, till today, and I want to tell 130 crore fellow citizens, nowhere has there been any discussion or talk on NRC. Congress and its associates, city dwelling urban naxals, are spreading rumours that all Muslims will be sent to detention centres… the rumours of detention centres spread by Congress and urban naxals are lies fuelled by the object of dividing the country. It is a lie.” The emphasis was unmistakable, with the speech delivered at the Ramlila Maidan within earshot of Old Delhi. The discussion whether CAA was ‘linked’ to NRC held attention and Modi’s remarks were seen to have contradicted other pronouncements, but the line drawn by the prime minister has since not been altered.

After the rules were notified on March 11, protests remained muted with previous hotspots like Shaheen Bagh witnessing no disruption. Local residents said a lot had been explained with regard to CAA and the law was no longer seen as a threat unlike the case earlier

Although statements on NRC remain a relevant point of discussion, the real issue for CAA’s opponents is acknowledging that the law has a historical rationale and minorities in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan (particularly during spells of Taliban rule) have faced rigorous discrimination. This has led BJP’s opponents to contest the diminution of Hindu populations in Pakistan and Bangladesh while arguing that CAA is discriminatory against Indian Muslims. The Supreme Court will examine arguments that CAA runs afoul of the right to equality and the exclusion of other minorities, such as Tamils in Sri Lanka and sub-sects within Islam who face persecution as well. The Tamils of northern Sri Lanka who left the island nation during the years of turmoil were located in refugee camps in India and some were granted citizenship. Many were repatriated after negotiations with governments in Colombo. Sri Lanka was not affected by the transfer of population post-Partition as were the nations mentioned by the CAA law. Neither Ahmadiyyas nor Rohingyas are in the same category as the populations impacted by Partition, even as Muslims are eligible to apply for refugee status and citizenship. Speaking in Parliament during the passage of the CAA Bill, Union Home Minister Amit Shah had said that more than 560 Muslims from these three countries have been granted citizenship in the last five years. He added that the previous UPA government had granted citizenship to 13,000 Hindus and Sikhs only but the Modi government is giving citizenship rights to six persecuted minorities, including Hindus and Sikhs.

The anti-CAA violence and the sudden advent of the Covid pandemic in March 2020 had led to the postponement of the framing of rules for implementing the amended citizenship law. There was concern that the law’s opponents were also targeting legitimate exercises like the Census and the updating of the National Population Register (NPR). The matter remained dormant till late 2023 when reports of the government’s plans to frame the rules and open a portal to invite applications began to circulate. The rules were finally notified on March 11 and while some opposition parties criticised the decision, protests remained muted with previous hotspots like Shaheen Bagh witnessing no disruption. Local residents said a lot had been explained with regard to CAA and the law was no longer seen as a threat as had been the case earlier.

The rules, as stated in the law itself, make exceptions for Sixth Schedule and Inner Line Permits in the Northeast where the government has promised to protect local traditions and customs and ruled out fresh inflows of population. The provisions of CAA are seen to be at odds with the Assam Accord which sets March 25, 1971 as the cut-off date for identifying and expelling foreigners. Assam’s anti-outsider politics has run on sentiments against Bengali speakers but BJP has been able to present illegal immigration from Bangladesh as the primary problem and threat to the region’s demographic and economic stability. So far, this has enabled BJP to retain support in Upper Assam as well as in the Barak Valley where Bengali-speaking Hindus are an important segment. The CAA rules and the portal have just about become operational and the grant of citizenship by way of registration or naturalisation may take some time. It also remains to be seen just how many eligible applicants there are as the number may not be of the order some apprehend.

The notification of the CAA rules led to BJP leaders proclaiming that another important manifesto promise has been fulfilled; another pledge had become a reality. The electoral impact might be seen in West Bengal where the Matua, Rajbanshi and Namasudra communities are expected to benefit from the decision. Some Muslim community leaders like Maulana Shahabuddin Bareilvi said that past misunderstandings have been cleared and the law does not discriminate against Indian Muslims. CAA, along with the abrogation of Article 370 with regard to Jammu and Kashmir and the consecration of the Ram Mandir, can be seen as the completion of BJP’s ideological agenda. Thus, it should convince its base that the party has delivered while also adding fresh adherents. The passage of a Bill to implement a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in Uttarakhand on February 7, 2024 marked another achievement, with the law expected to be a template for other states where BJP is in office, although that is not immediately on the cards.

All of these decisions feed a political-cultural vision that believes the restoration of the rights of communities and people who became victims of Partition is an essential part of India’s duties and is linked to its identity and national consciousness. The Ram Mandir, for example, is seen as a resetting of India’s cultural compass by acknowledging the just and legitimate beliefs of millions and the centrality of Lord Ram to India’s social and cultural ethos. Ever since Modi was named BJP’s prime ministerial candidate in September 2013, the electoral battle between him and his opponents has often been labelled a clash over the “idea of India”, with both sides offering sharply differing viewpoints. The anti-Modi narrative sees BJP as promoting majoritarianism and the government’s actions as an attack on secularism. Modi has countered allegations of bias by pointing to the non-discriminatory nature of his government’s programmes even as he does not hesitate to refer to Mughal-British rule as 1,000 years of servitude. BJP has long held that privileging sectional interests is actually anti-secular, or pseudo-secularism, and ends up widening inter-religious differences. Pandering to communal interests strengthens conservative elements within communities who then promote separateness and weaken progressive and integrative voices. In this clash of ideas, BJP’s success in realising its core ideological objectives and gaining public acceptance indicates it is winning the battle of hearts and minds.

The notification of the CAA rules and the first applicants who will get Indian citizenship will figure prominently in BJP’s campaign as the party leverages Modi’s “nation first” policies and targets Congress and other opposition parties for indulging vote banks at the cost of genuine refugees with nowhere to go but India. Shah has played an important role in forging BJP’s political strategies in the Northeast and West Bengal and the home ministry’s role in implementing CAA makes him a key leader who will articulate the party’s and government’s rationale. Shah has not pulled his punches on the need to halt illegal immigration—even as opponents accuse him of using harsh language—and that remains a key theme for the elections in the Northeast and West Bengal. CAA does, in this context, distinguish between those who have a legitimate claim to sanctuary and succour and others who were not made to pay the costs of Partition.

For more pictures click here

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover_Kumbh.jpg)

More Columns

The lament of a blue-suited social media platform Chindu Sreedharan

Pixxel launches India’s first private commercial satellite constellation V Shoba

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita