In the deep forests of Gadchiroli, the only battle is to fool death.

Two things arrived last month in Pavarvel village in the Naxal-affected area of Gadchiroli, about 220 km from Nagpur. The first arrival was of a baby boy born to an Adivasi woman, Indu Bai. He died within an hour of his birth. The mother followed a day later. In Pavarvel and all other neighbouring villages, pregnancies are handled by elderly women. For everything else, there is Devi puja, since there is not even a primary health centre around. There is no electricity, but the villagers claim that a Gram Panchayat official comes every year to collect electricity tax. Water comes from a ramshackle bore-pump.

The other arrival was that of a police party. It had not come to apprehend Naxalites who villagers say turn up at any hour every now and then, demand food, and slip back into the jungle. Pavarvel itself is in the thick of forest. There is hardly any road, and if you don’t have a local guide, it could take you weeks to figure out your location. In the forests, dense with Mahua and other trees, there are memorials erected by Naxalites in memory of their fallen comrades.

So, yes, the police arrived and went straight to Bajirao Potawe’s house and beat him up. “With their boots and lathis,” he says. “They said bad things to my mother and sister, called me a bastard, and said how dare my family accuse them of rape,” he recounts. Then they made him run errands like fetching water to cook a meal of dal and rice they had brought along. Potawe himself hasn’t been able to eat such meals for a long time. In fact, he has been living with his wife without a marriage ceremony; it would’ve taken a feast for his fellow villagers, and for them to gift the couple some rice. There simply wasn’t enough. Rice is a luxury for Potawe and his neighbours.

The rape which the police party referred to happened with a 13-year-old girl, the sister-in-law of Bajirao Potawe’s brother, Kaju Potawe. The girl, from the neighbouring village of Tudmel, had come to his sister’s house for treatment of an illness through Devi puja, and had stayed back, working as a labourer at a school construction site nearby. It was on the evening of 4 March 2009 that a party of Maharashtra Police’s C-60 Commando group—a special anti-Naxal force of policemen mostly from Adivasi regions—came to Pavarvel, led by their notorious commander Munna Thakur. Reports suggest that the group saw a man running with a tribal water-flask made of dried pumpkin. The police fired at him, but he got away. It was the misfortune of the Potawe family that the man ran off towards the forest behind their house. Within minutes, the police party entered their house and clobbered Kaju Potawe, who had just returned from the jungle with wild berries. “They kept asking about Naxal whereabouts. When I said I didn’t know, they hit me even more,” he says.

It was then that the police party saw Kaju’s sister-in-law, the 13-year-old. “They dragged her by her hair and accused her of being a Naxal,” says Kaju. Later, they asked another villager Dayaram Jangi and his family, and also a school teacher they had put up, to vacate their house. The girl was forced into the house and held captive along with a few men of the village who the police suspected of being Naxals. The next morning, she was taken to a nearby field. Blindfolded, with her hands tied, she was raped several times.

A fact-finding team that visited her after the incident was told by the girl that the police did ‘badmaash kaam’ with her. She told them that the first person who raped her was Munna Thakur. “He said I must have heard of his name as he pushed himself on me,” the girl told the fact-finding team. The girl added that she had fainted several times during her ordeal.

At about 10 am, a helicopter landed in Pavarvel to take the girl and other suspects to Gadchiroli town. In a place where there’s not even a bullock cart to take an ill person to hospital, the state machinery spared a helicopter to ferry a 13-year-old girl accused of being a Naxal. Of course, no charge was proven against her. As a damage-control exercise, Munna Thakur was later transferred.

Just how does the State expect the people of Pavarvel to inform them of Naxal whereabouts? That too, when this is not the only instance of police atrocities in this village? In 2006, 17-year-old Ramsay Jangi was picked up by C-60 commandos and beaten up severely. When his cousin Mathru Jangi went pleading that he was innocent, the police assured him that he will be freed after first-aid. That night, the villagers saw Munna Thakur. They heard him shouting at his men, instructing them to ‘finish off’ the work. A moment later, they heard gunshots, several of them. The police had shot Ramsay Jangi dead. The body was taken to Dhanora taluka.

After ten days, the police came back and asked Ramsay’s father Manik Jhangi to come and collect his son’s body. But nobody went, fearing arrest. The police disposed off the body.

Manik Jhangi has kept the empty cartridges of the bullets that killed his son. “My son’s body must have rotted,” he whispers.

“No, they inject something inside the body to keep it fresh,” interjects a boy with some education. “But he is gone, gone forever,” Manik Jhangi sobs silently, his tears mixing with sweat.

“We fear going into the jungle now because if the police finds us, they will kill us,” says a man.

“Tell me, how are we supposed to survive?”

I arrive in Gadchiroli after spending two weeks in Andhra Pradesh, mostly in the erstwhile Naxal bastion of North Telangana. This is the area that top Naxal leaders like Ganapathi and Kishenji come from. It is from this region that a number of bright young men and women—engineers, eye surgeons, PhD students—turned revolutionaries. Almost 30 years before that helicopter landed in Pavarvel, the first squad of Naxals came to Gadchiroli after crossing the Godavari river from Andhra Pradesh’s Adilabad district. It was led by a young Dalit boy Peddi Shankar, who worked in a coal mine before he turned Naxal. Shortly afterwards, he was shot dead in an encounter with the police on the banks of Pranhita, a sub-river of the Godavari. Within 2-3 years of his death, the Naxal movement spread like wildfire in this region. Naxals first targeted contractors involved in the tendu leaf (used in beedi making) and bamboo trade. These contractors would fleece poor Adivasis and pay them a pittance for a hard day’s labour. After the Naxal intervention, these contractors were forced to pay better. Naxals also went after government representatives like forest and police officials who would often harass and exploit Adivasis. The police tried to wrest control from Naxal hands, but it was too late. Gadchiroli was soon made part of Dandakaranya, the Naxal guerilla base. The police just couldn’t act against them, and it ended up alienating the local populace further through a sustained programme of repression. The scenario now is more or less the same. Unable to act against Naxals, the police end up killing boys like Ramsay Jangi. And infuriating villagers in places like Pavarvel.

A day after the Dantewada attack, Gadchiroli is tense. In Armori, a town on the Nagpur-Gadchiroli road, I wait at a local activist’s house over a breakfast of puffed rice, jalebi and tea, while he tries to find me a resource person in an east Gadchiroli area. It is after several attempts that the activist gets through on the phone. The conversation lasts 2-3 minutes. “He is worried and says you shouldn’t come here,” the activist says. “Actually, the police is on the prowl. Anyone who goes into a village gets noticed, and after you are gone, they will harrass my friend,” he clarifies. But elsewhere, I need to take chances, he tells me. I take my chances, and that is how I get to Pavarvel. And in touch with a CRPF patrol party.

The trees are bare, and the young soldiers of the CRPF long for some shade. In about eight weeks, the trees will be full of foliage. But before it can bring some comfort, it could take these men closer to death. From behind the thick foliage, Naxal guerillas could zero in unnoticed and do a Dantewada on them. The CRPF party has arrived in a deep forest zone of Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli region at about 5 am in the morning, carrying packed lunch and water filled in empty Fanta bottles. The water lasts only a few hours. There is nothing to do, except wait under the oppressive sun and ward off flies adamant on clinging to your skin. The eyelids droop in fatigue, but here that could mean death. It has just been a day since 76 of their colleagues died in Dantewada. “We are all scared,” says one, “Some want a change of job.”

The morale of these men in uniform couldn’t be lower. Ever since the Dantewada incident, the phones haven’t stopped ringing. Anxious family members and relatives are calling every hour to check whether they are safe. The people who died in Dantewada were colleagues, batchmates, and in conflict zones like Kashmir, some of them even became soul mates. “I lost one of my batchmates in Dantewada,” says their officer, wiping sweat from his brow and from the ammunition magazine of his AK-47 assault rifle. “We are fighting a lost battle. We don’t know who our enemy is. Adivasis share nothing with us.”

The officer talks about visiting several villages, tracking Naxals. He says most of them don’t understand a word of the language spoken by Adivasis. Those who do, get no clue from villagers. “We have even tried asking young children, but not a word comes out of their mouth. We have no intelligence at all,” he says.

The group has walked in the morning as part of a road-opening party to ensure that this stretch is safe for their vehicles and men to move on. “Move on where?” he asks. “We are all waiting for evening so that we could retire to the camp,” the officer says. He takes a big gulp from his water bottle and it is over. “You think we are fighting for India?” he asks, and then replies himself. “Jhaat ka baal…!” he lets out a familiar expletive, “We are fighting to save our lives. Do you think this bullet-proof jacket will save us if a 70-kg explosive explodes beneath our feet?”

As an officer, back in camp, he may get a fan, but none of his men would have that luxury. They will sleep in tents with no fans, braving vicious swarms of mosquitoes.

“Saala, yahan ka macchar bhi Naxali hai,” quips a soldier. All of them laugh.

There is the sound of a motorcycle on the nearby road. The laughter vanishes. Fingers go back to the trigger. The other hand feels for the walkie-talkie. Day or night doesn’t matter around here—there is no rest.

The officer says he was on deputation with a special force in Delhi. “Every morning I would run 20 miles to keep myself fit so that I am not asked to leave the force and hence Delhi. But now I am here in these treacherous forests, counting every day the way prisoners do in jail,” he says.

It is still many hours before the party can hope to retire for the night.

“When you write this report, please write that wars are not fought from tents,” says the officer, shaking his sweaty hand to emphasise the point.“We don’t want our bodies to be injected with formalin, as they did with those who died in Dantewada, and then sent back home,” he says as I get back into the car.

I roll down my car windows.

The car engine grunts, but the officer’s voice reaches me above the noise. “Everything ends with formalin,” he says.

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/naxalism-1.jpg)

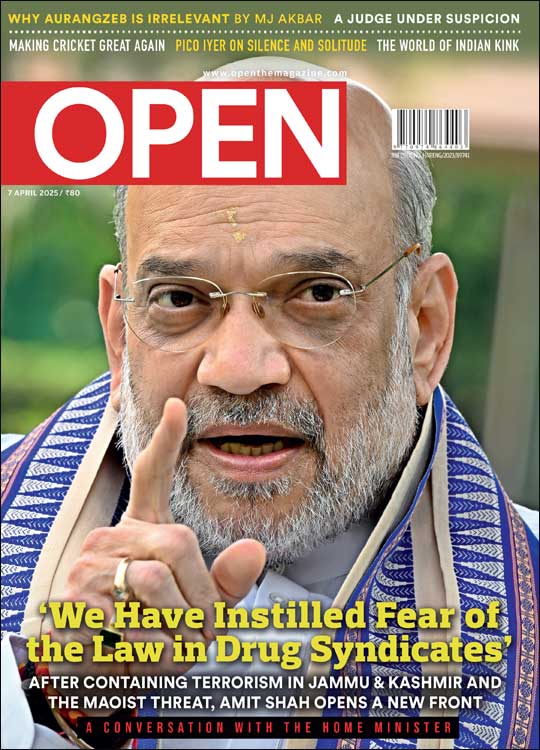

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

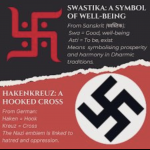

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post