The Sum of His Many Parts

A decorated war hero on love, bachelorhood and why Gen VK Singh is an honourable man

Aimee Ginsburg

Aimee Ginsburg

Aimee Ginsburg

|

01 Jun, 2012

Aimee Ginsburg

|

01 Jun, 2012

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/singh1.jpg)

A decorated war hero on love, bachelorhood and why Gen VK Singh is an honourable man

You are pacing the veranda of the military HQ in a city behind enemy lines. You are alone, unarmed. Minutes earlier you have issued an ultimatum—‘surrender or suffer the consequences’—to the highest commander in the land. The other officers present voiced their extreme displeasure at your bold demand but you were unfazed.

You explained yourself coolly—logic your sword, faith the shield. You spoke, and stepped out to the veranda, awaiting the commander’s reply. The lives of millions hinge on how he responds to your no-nonsense threat. Only you know you have been bluffing. You know this to be a defining moment of your life. You are using all your control to appear calm as you pace back and forth. You are completely alone.

This is a solitude both regal and rare.

There was a woman who meant the world to you. You both loved to dance. She made you happy. She wanted something you couldn’t give her at the time, and she wouldn’t wait. You think of her still, of combing her long shiny hair while she sat in your room and laughed. Decades have passed, your outstanding achievements, in war and in peace, are well chronicled, the forests you saved from destruction pulse with new life. But you’ve never loved another woman.

This is a solitude of another kind.

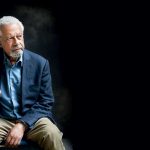

I first saw Gen Jack Jacob ten years ago, during the Sabbath services at the Judah Hyam synagogue, Delhi’s only Jewish temple. When he walked through the door, the (small) sea of congregators parted and an excited hush filled the hall. “It’s Gen Jack Jacob!” the lady next to me, beautiful in her Sabbath salwar of turquoise silk, whispered in my ear. Her husband’s back straightened discernibly; “Gen Jacob is our topmost Jew!” he said. Of that long ago evening of prayer, that suddenly upright back is what I remember most. “People throw around the phrase ‘larger than life’,” the Israeli ambassador said to me that night. “Not many people fit the bill. Lt General Jack Jacob is larger than life.” Jacob, a large man with silver hair and posture becoming of his rank, was immaculate in his navy blue suit. Far removed from military affairs and not interested (at the time) in matters of my tribe, I looked, nodded and moved away.

Years later, environmental and social activists in Goa introduced me to Jacob’s remarkable legacy as the state’s most effective and beloved (ex) Governor. Later still, the General’s autobiography An Odyssey in War and Peace became a besteller. I wrote to him finally, asking for a series of interviews. Eight minutes later, his reply was in my inbox: ‘I am approaching 90. I think I have earned a rest. I intend to now slowly fade away. If you want to write about me, you better be quick. Regards, jfrj.’

Lt Gen Jack Farj Rafael Jacob is best known for almost singlehandedly ending the 1971 Indo- Pakistan war and for his successful terms as governor of Goa and Punjab. Now, like then, he lives alone (apart from loyal staff). The governors’ mansions he once occupied were grander than his modest flat in the capital, with its piles of books—mostly on military affairs—on the living room table. He serves tea in exquisite china, salty crackers on the side. He has never married. “I did not remain single by choice,” he says, “I tried twice, but failed.” The first of his former loves now lives in Jerusalem. The other, The One, still tugs at his heart, the memories like postcards, vivid yet flat. His recall of details is startling, something he was known for back in his army years, a skill pointed out by the Pakistani commission that studied their defeat in the war. Jacob calls himself “a dal-chawal kind of guy”, but the boot hardly fits, though this is indeed his favourite dish, alongside hameen and beetroot kuta with cooba, the Jewish-Calcutta dishes of his childhood. “I’ve taught my cook to spice them up, though,” he says, finding the original recipes too “boring and bland”.

‘I have found that the Indian military hierarchy is more interested in compliant malleability than in an aggressive outlook,’ he writes in his memoir, ‘They think aggressive means quarrelsome… This attitude is still true today.’ This aggressive officer’s famous act of bravery in the 1971 war has been analysed in textbooks around the world. (Invited by the governor/commander of East Pakistan armed forces Gen AAK Niazi to discuss a ceasefire, Jacob penned an instrument of surrender and flew with it to Dacca (now Dhaka), unarmed. For efficiency’s sake, he did not fully inform his superiors in Delhi of his plan. At enemy headquarters, he told the Pakistani Commander that he could surrender, publicly, and receive the protection of the Indian Army for all minorities and retreating troops; or face the results of an Indian onslaught. Niazi accepted, and 93,000 Pakistani soldiers surrendered, the only public surrender in modern history. Jacob had only 3,000 Indian troops behind him at the time. Later, Niazi (whose decision to surrender is itself a form of heroism) told the Pakistani investigative commission “Jacob blackmailed me!”)

Uncountable multitudes were saved by this surrender, by the cessation of the civil war and its atrocities. Last month, the (Muslim) Republic of Bangladesh awarded Lt Gen. Jacob a certificate of appreciation for his ‘unique role’ in the formation of the nation. That he is a Jew makes this all the more remarkable.

Jacob was born in Calcutta, in 1923, to a deeply religious Jewish family of Iraqi origin. His mother was lovely. There was a tree in the neighbourhood—called the Grandmother Tree—he used to hug tight. When his father fell ill, he and his two brothers were sent off to Victoria, a boarding school high up in the Darjeeling hills. He excelled in his studies and fell in love with the virgin forests—the lichens, the ferns, the gushing jhoras (mountain streams). Roaming the mountains with his best friend, he developed his lifelong passion for the outdoors and all “flora, fauna and lepidoptera”.

As a teenager, he liked to read the poems of the war poets—Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, Julian Grenfell. In Calcutta, his family adopted a family of Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Europe. “I was appalled by their stories, by the atrocities,” he says, “…and influenced by the poets as well, I decided to join the Army and fight the Nazis.” Jacob’s father disapproved of this decidedly unorthodox career choice, but eventually gave his blessing out of respect for his son’s motives. “I never experienced anti-Semitism among fellow Indians,” he says, “but got a taste of it from the British in school and during my service in their army.” After Independence, Jacob rose in the ranks of the Indian Army. In 1969, Chief of Staff Sam Manekshaw appointed Jacob Chief of Staff, Eastern Command.

“I prefer the company of military men,” says Jacob one afternoon, indulging my company for a few hours. He likes the questions to come rapid fire and bounces back his answers instantaneously, precise and spare. As I struggle to keep up an intelligent flow, he offers me a drink. I accept—Old Monk and soda—but find myself drinking alone as the General sits by my side on his gold brocade sofa, chin on chest, ready for my next question. On the wall before us, a fine oil painting in greys, blues and browns, his own work, portrays his unit in the hours before combat. In the diffused afternoon light, his soldiers look hauntingly real.

Long ago, Jacob’s commandant at Staff College told him he must learn to suffer fools. Once, when still a Major, he threw a serving Brigadier out of his officer’s mess for his unending rudeness. Jacob writes openly about his peers and superiors, as generous with his praise as unstinting in his criticism, all couched in amusing anecdotage. “Everything I have written can be substantiated in the records at army HQ,” he says.

General, what do you think of (exiting Chief of Staff) VK Singh and the quasi scandal/s he has been involved in lately?

“Singh is a very good and honourable chap, unlike some other Army chiefs who have bent over backwards to please their political masters. The mudslinging at him is uncalled for.”

What did you think of the story about the supposed coup?

“The story is nonsense.” Jacob, not one to be outdone, gazes fondly into history and recalls the time he himself triggered alarm in the halls of power. “During my stint as commander of the Eastern Command,” he recalls, “I decided to hold a tattoo (fundraiser) in Calcutta, and ordered five tanks to come the five-point crossing as part of the games. Soon after the tanks took position, facing out from the centre, I received a frantic call from the Commissioner of Police. He said ‘General! There are tanks in the centre of town!’ He was afraid we had taken the city.” As he reminisces, a hint of a grin moves across the General’s face.

After retirement, and an unsatisfactory stint in the business world, Jacob joined the BJP as advisor on military affairs. He was appointed Governor of Goa in 1998, during a period of profound political instability in the state. In the months following his appointment, several state governments were formed and fell. ‘Politics in Goa is akin to musical chairs,” he writes in his autobiography. Finally, in 1999, Jacob collected from all state party leaders their request to impose Governor’s rule.

In a review edit, as Jacob was about to leave Goa to take over his new charge as Governor of Punjab, the Herald wrote: ‘Lt Gen Jacob demonstrated that the state could be administered efficiently by just a team of three…’ When he took charge of the administration of the State, it says, ‘the economy was in a shambles and the state virtually bankrupt… Lt Gen Jacob rose magnificently to the new challenge with his “hands on” style of governance [and] total commitment to the ordinary citizens of the state.’

Jacob came to work every day and on time, forcing everyone to follow suit. He consolidated and paid back high-interest loans with the help of his BJP friends at the Centre. He made surprise visits to bureaucratic institutions, and opened his office to all citizens and their complaints. He paid for a trip to a conference abroad out of his own pocket. But what he is most remembered for in Goa is his aggressive manoeuvres to save two large tracts of jungle from mining. “The irresponsible open-cast mining… was a catastrophe,” he says, “I was appalled.” Jacob turned them into nature reserves, in a legally airtight manner. “The politicians and the mining companies were up in arms,” he says, “This is the best thing I have ever done. Even the tigers have started to return.” ‘Indeed, the ordinary citizens were so happy (with Jacob),’ wrote the Herald, ‘that there were demands that Governor’s rule should be extended. Of all the Governors who served in Goa, Lt Gen Jacob was the best by any yardstick.’ The ex-governor has not been back since, and declines my suggestion that he come and view the beauty of the sanctuaries he helped create. “I never retrace my steps,” he says.

When Jacob went off to fight in WWII, he carried a slim, rice-paper edition of the Oxford Book of Modern Verse in the back pocket of his uniform. “I like the modern poets,” he says, “…WE Henley, GM Hopkins, WB Yeats, Padraic Colum; I particularly like the war poets. I used to read from this book during lulls in the operations.”

And he quotes, eyes closed, as we sit together in his flat, two days shy of his 89th birthday, during this impossibly long lull in operations he now finds himself in:

It matters not how strait the gate, / How charged with punishments the scroll, / I am the master of my fate: / I am the captain of my soul.

(from ‘Invictus’ by WE Henley)

Still, Jacob (Jake to his few lucky friends) prefers to speak of less private things than poetry. The general, an enthusiastic angler, who once sent his catch—a record-breaking 9lb trout in an 11,000ft high stream—to his chum, the King of Bhutan; an amateur painter of impressive skill; a lover of antique art; a fan of Western classical music (and sometimes the Beatles) is beginning to feel his age. Recently, he decided to give up golf. His brothers are gone; he has no contact with extended family members. The Jewish community of Calcutta has mostly migrated to Israel and is now virtually dead. He doesn’t accept many invitations anymore preferring to keep to himself; there are visitors to his flat, but few.

“My friends and peers are all gone,” he says. He worries about being a burden when he becomes truly old, and hopes to go before he reaches that point.

“I have never been a very religious man,” says Jacob. “I believe in God, I can say a few Jewish prayers, but that’s it. When we were young, our parents hired tutors to teach us Hebrew. Unlike my brothers, I was not bothered to learn. I regret that now.”

Jacob, who appears in John Colvin’s book about Jewish military heroes, titled Lions of Judah, has been to Israel many times, and engaged in some behind-the-scenes diplomacy to foster Indo-Israeli relations. Over the years he has developed friendships with some of Israel’s leaders, both military and political, including current President Shimon Peres. Jacob’s uniform hangs in the Israeli military museum. Asked if he was ever tempted to move to Israel and offer the country his military expertise, he says “Israel has outstanding military leaders of their own, they do not need me. Besides, India has always been very good to us. I am proud to be a Jew, but am Indian through and through. I was born in India and served her my whole life. This is where I want die.” Jacob calls in his servant to turn on the lights; dusk has fallen on New Delhi, and though I don’t want to leave him, he would really like to be done. I hesitate at the door.

General, do you know the old Jewish saying, ‘He who has saved one life is as if he has saved the whole universe’?

“I wouldn’t know about such things,” he says, and wishing me farewell, slips back into his shell.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Manosphere.jpg)

More Columns

‘Colonialism Is a Kind of Theft,’ says Abdulrazak Gurnah Nandini Nair

Bill Aitken (1934 – 2025): Man of the Mountains Nandini Nair

The Pink Office Saumyaa Vohra