The Madness in Her Method

A desperate Bengal ousted the Left, seeking ‘poribarton’. Six months on, Mamata Banerjee is as vocal as she was while lavishing poll promises, yet ‘change’ looks elusive as ever. So, what’s holding back poribarton?

Jay Mazoomdaar

Jay Mazoomdaar

Jay Mazoomdaar

|

18 Nov, 2011

Jay Mazoomdaar

|

18 Nov, 2011

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/mamata-poroborton.jpg)

A desperate Bengal ousted the Left, seeking ‘poribarton’. Six months on, Mamata Banerjee is as vocal as she was while lavishing poll promises, yet ‘change’ looks elusive as ever. So, what’s holding back poribarton?

Popular wisdom often cliché. And Charles Darwin, if not Alphonse Karr, is well known anywhere in the world. But in Bengal, they are still quoted routinely to drive home a point.

Yes, it took three-and-a-half bleak decades. But when eventually Bengal bit the bullet, it was all about poribarton— from a regressive, anachronistic government and an all-encompassing ruling party. So this May, after defying anti-incumbency for 34 years, the longest serving elected Left government fell to the English naturalist’s theory, its failure to adapt finally catching up with it.

Today, it is the turn of the French novelist. West Bengal has become Poshchim Bongo; Tagore songs are adding to the noise at Kolkata’s traffic signals; and former Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya has gone into a permanent sulk. But six months after the momentous regime change, things in Bengal remain much the same.

But a fondness for cliché is hardly something to write home about.

BIG ASK, NO INTENT

It was never going to be easy to turn Bengal around. Even in its rout, the Left secured 41 per cent of the vote. The party is deeply entrenched in the state’s social and administrative systems: from cultural icons to teachers to bureaucrats, the majority was either co-opted by the party or were bona fide Left cadres. They cheerfully toed the party line for personal gain. It is practically impossible to replace this corrupt and defunct system. It is one thing to have defeated the Left, but bringing about change at the grassroots (literal translation of Trinamool) was always going to be a tall order.

The state’s infrastructure is in tatters and rebuilding it will need heavy investment. The Maoist conflict and unrest in Jangalmahal in Purulia district or Lalgarh in West Midnapore were horribly mismanaged by the Left to flashpoints. The hills in the north are suffering from a longstanding conflict. Political control over public affairs, blinkered populism, poor work ethics and the subsequent loss of industry, jobs and capital have reduced Bengal to a socio-economic blackhole.

Given the odds, few would have expected Mamata Banerjee to fulfill her lavish electoral promises. Yet, after handing her a generous mandate for a turnaround, her voters have reason to doubt her very intent. Consider these:

» Admitted, Mamata inherited empty coffers. But the early euphoria over the ouster of the Left would have allowed Mamata to come up with a few tough fiscal measures to raise funds. A former journalist close to the new CM says she has not lost her pre-election populist reflexes—she has even scrapped the water tax Buddhadeb levied under the Centre’s Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission.

Mamata is dealing in symbolism that does not cost money: the law to return Singur land to farmers; the visit to Darjeeling and Sikkim; the tough posturing on Teesta waters; and playing the media on Jangalmahal and Gorkhaland. All this while hoping and looking expectantly at the Centre for a bailout, and embarrassing herself with bargains on the fuel price hike.

» Cashing in on the Left excesses at Lalgarh and Jangalmahal, Mamata had promised to punish the guilty, stop police atrocities, withdraw false cases and open dialogue. But once in power, she did a volte-face, say organisations working in these areas. Nobody was released; in fact, fresh arrests were made; the joint forces simply changed strategy to create an illusion of a ceasefire and focused on targeted operations; those guilty of mass murder and rape walked free.

An activist of the Nari Ijjat Bachao Committee offers an example. At Chanpadoba under Belpahari police station, the village commons had built a health centre in 2008. But the joint forces fighting Maoists soon occupied the building. After the much-anticipated regime change, villagers tried to inaugurate the health centre on 14 August. The new administration and its forces did not allow them.

Instead, Mamata is promising development and 10,000 temporary jobs as special police officers. But there are few takers for “symbolic development without democratic rights” among the locals, who dismiss the job scheme as Mamata’s ploy to trigger a fratricide among tribals. What made matters worse was the involvement of the Bhairav Bahini (an armed gang backed by the TMC) in the operations of the joint forces.

In the run-up to the polls, Mamata rushed to stand by every victim of alleged police/Left atrocity. However, in Jhar- gram to address a rally on 16 October, she refused to visit a woman in a nearby hospital who had consumed poison the day before after being assaulted at her Belpa- hari home by cops on the lookout for her husband. The victim’s husband says the CM turned away the locals who met her, saying “Jangalmahal women lie a lot”.

» The TMC’s command structure is far from robust and too many goons who had earlier served Left interests have simply changed sides, as have some renegade Communists. While some of these new entrants are taking on old-timers in their new party, others are busy settling old scores with the comrades they deserted.

Mamata’s own conduct undermines her promise of restoring the much-politicised state police to a professional, independent force. The Chief Minister made national headlines on 9 November by storming a South Kolkata police station to free a couple of goons from her own city neighbourhood who had been detained for vandalising the police station.

“No Left cadre would have publicly assaulted a police officer. No Left minister or even leader would have gone to a thana to release hooligans. Of course, they would have ensured the same results without getting personally involved,” says a veteran IPS officer.

» With every Mamata loyalist and his uncle turning up for their share of the spoils, former incumbents in key posts (some even deserving) have been summarily removed. Members of the TMC education cell, many of them with a Left history, have been handpicked to head bodies such as the School Service Commission, the Primary Education Board and the West Bengal Board for Secondary Education. Even non-Left factions in different university and college teachers’ unions complain that the new government’s attempts at reform are as arbitrary and unilateral as its predecessor’s. The new government has also redrawn the lawyers’ panels for all its departments.

»The new Chief Minister faces an acute shortage of people she can depend on to get the job done. She got elected many nondescript carpetbaggers who can contribute little as MLAs or ministers. And of the few who can, she doesn’t seem to trust any.

As a result, she takes decisions for all ministries, talks to the media on all issues (often incoherently) and even decides which sofa goes where in the secretariat. Six months into the job, there is no government spokesperson and no second-rung leadership in the party. And there is only so much a one-woman government can do, even if Mamata often puts in 18 hours a day.

TALE OF TWO CMS

Since she entered politics, Mamata’s biggest success has been to stand up against the Left bullies and show that it is possible to do so. But her three-decade-long fight could still not have brought about this regime change but for a metamorphosis she had no role in. The new CM has good reason to learn from her predecessor’s failings. Consider these:

» In 1993, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya resigned from the Jyoti Basu government. Frustrated with the rot in the Left movement, he wrote a candid play—Dussamay (Bad Times)—to record his disapproval. A staunch idealist, he flaunted his anti-capitalism credentials, at times rather naively, by refusing to attend functions hosted by industrialists.

Cut to 2006. Buddhadeb has won his first poll as Chief Minister and the first person he meets after taking oath is Ratan Tata. Eager to resurrect the state economy and create his own legacy, he starts wooing capital, and, recalls a former bureaucrat, makes new friends in a hurry. So dramatic is the switch in loyalties that he unceremoniously dumps one of his most trusted aides, a bureaucrat-turned-friend, for cautioning him about a dubious businessman. Said businessman has already won over the new government by modifying investment plans on the thousands of acres he was promised by Buddhadeb.

Years before she became Chief Minister, Mamata stood by an upright Muslim IPS officer who took on the Left government. She went so far as to put it in writing that she would appoint this officer the Commissioner of Kolkata Police if she came to power. Soon after she became the Union Railway Minister in the second UPA Government, Mamata called him to Delhi to work in her ministry.

Cut to 2011, and the new Chief Minister has appointed as Kolkata’s Commission- er of Police RK Pachnanda, a “Left stooge” whom she accused of tearing her sari and biting her during a protest rally in 1998 and vowed to punish once she became CM. Having in fact superseded the IPS veteran she once backed by appointing Pachnanda, she kept the officer out of the police force and offered him a posting in the CMO that he has since declined.

The U-turn is apparently a fallout of the good cop’s refusal to toe her line in the Railway Ministry, where Mamata sat on his report against a top security officer from the UP cadre. The new CM, claim sources, decided in favour of a more “pliant officer to ensure smooth functioning of the government”.

» Buddhadeb at the helm also did away with the regular line of command. For instance, no top cop could ever approach Jyoti Basu directly in any crisis. He would go to the home secretary (HS), who, if required, would consult the chief secretary (CS), and it was up to the CS to decide if he wanted to refer the matter to the CM. At whatever level a decision was taken, it was communicated down the hierarchy. In effect, a top cop would never know if a decision came from the HS or CS or CM.

While independent judgement at different levels would make for a better decision, the CM could distance himself from any decision gone wrong. But Buddhadeb sat with top bureaucrats and cops in his office and discussed issues like club buddies would. A few candid IAS and IPS officers could still have salvaged these debates, but the CM increasingly handpicked yesmen who rarely interrupted him.

Most of Mamata’s decisions too are unilateral with little input from the bureaucracy, cabinet or party colleagues. It’s not a coincidence either that none of her top ministers—former home secretary Manish Gupta, former Andrew Yule HR executive Partha Chatterjee or former FICCI secretary general Amit Mitra—has a political footing. The only senior Congress leader in the cabinet, Manas Bhunia, handles irrigation. Even Subrata Mukherjee, Mamata’s political mentor who gave her the ticket to contest her first Lok Sabha election in 1984, has been assigned an insignificant portfolio.

She went out of her way to accommodate a few officers from the Union Railway ministry not because of their record, but simply because she prefers, say sources in her own party, officers who will carry out orders.

» Buddhadeb has a tendency to take hasty decisions. In the early 1990s, recalls a senior police officer, the legendary owner-editor of the Amrita Bazar Patrika-Jugantar group, nonagenarian Tushar Kanti Ghosh was admitted to a Kolkata hospital. “I received an arrest warrant against Ghosh for irregularities in the employee provident fund. It was out of the question arresting him in that condition. I informed the Commissioner (of Police), who decided to consult Buddhadeb, the minister in charge of police affairs.”

When Buddhadeb heard the officers, he ordered Ghosh’s immediate arrest. “Alarmed, I pointed out that we might have to arrest the hospital bed as well. But the minister insisted, saying the Ghosh family were traditional Congress supporters. When I requested him to think over his decision, he left in a huff for the CM’s room.” Within minutes he returned and asked the officers to sit on the warrant. Jyoti Basu was apparently furious that Buddhadeb even thought of arresting someone of Ghosh’s age and stature in his condition.

Mamata’s political reflexes smack of the same impulsiveness. Playing the same partisan card the Left favoured, Mamata went to the extent of showing a number of cultural icons—writer Sunil Ganguly, poet Shankho Ghosh, playwright Mohit Chattopadhyay and actor Soumitra Chatterjee—the door in different government committees in favour of juniors such as Arpita Ghosh or Shaoli Mitra from the TMC camp.

POWER RUSH

There is certainly a pattern to Mamata’s recent utterances and action (or lack of it) in crises, ranging from the Maoist standoff to infant deaths in city and district hospitals. Sample these:

» “There are no Maoists-Phaoists in West Bengal.”

» “I’ll give you one last chance. How many jobs do you want? How many roads and hospitals? I will provide everything you want if you drop the gun.”

» “I am concentrating on industry. On infant deaths, if you still have some queries, ask my health secretary. Please don’t disturb me.”

» “Most of the babies who were admitted to the hospital weighed around 300 grams.”

At a recent function in Kolkata, where a road—Sindhu Kanu Dahar—was named after two heroes of the Santhal rebellion, she repeatedly enquired from the stage if Dahar’s descendants had made it to the inauguration. Dahar, in Santhali, means road.

Claiming that 90 per cent of her poll promises to minorities had already been fulfilled, she announced regularisation of 10,000 madrassas. Only, she never bothered to check if there were indeed 10,000 madrassas in the state.

But gaffes and outbursts may yet do little damage beyond headlines the morning after. In any case, Mamata doesn’t seem to care, having reached the seat of power that has been a lifetime’s work.

It was no mean feat for a lower middle class, godfather-less woman, all of 21, to become general secretary of the Mahila Congress in 1976, but her government’s official website, banglarmukh.com, will have you believe that she accomplished the feat as early as in 1970, as a 15-year-old!

Now that she is CM, she will need more than her natural flair for exaggeration to deliver poribarton.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

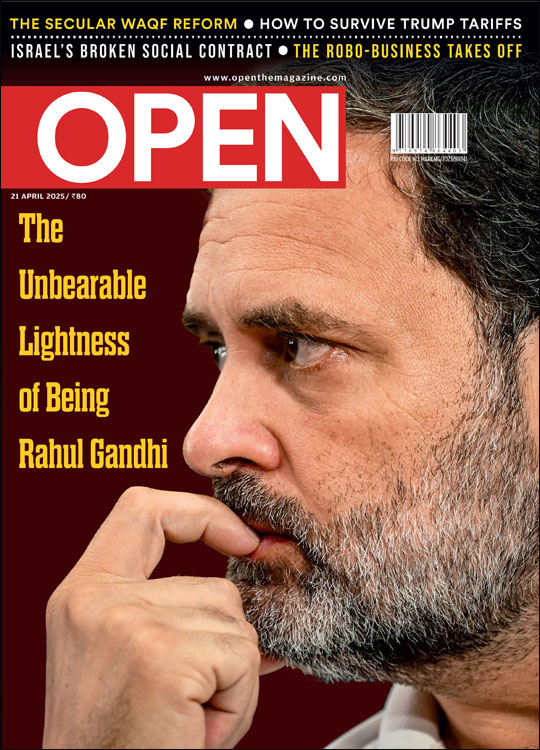

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

US Blinks On China Tariffs Madhavankutty Pillai

The Gifted Heir Sudeep Paul

SHAPING FUTURE IN THE INDIAN EDUCATION LANDSCAPE Open Avenues