Mind Your Mushrooms

Call them just another form of fungi if you want, but here is someone who expects them to save the world

Aimee Ginsburg

Aimee Ginsburg

Aimee Ginsburg

|

29 May, 2013

Aimee Ginsburg

|

29 May, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/mushrooms.jpg)

Call them just another form of fungi if you want, but here is someone who expects them to save the world

We are walking through Lucknow airport, a temple to the glory of concrete. A ground steward asks to see our boarding passes. Suddenly, in a flash, Paul Stamets, 57, eco-warrior and world-renowned Friend of Fungi, is no longer at our side; we find him bending over a homely little plant in a homely cement planter, a look of warm affection lighting his face. He gently fingers the three tiny mushrooms he has found hiding in the shade of the plant (which he has spotted somehow from across the corridor), tells us their name, gently pats them on their heads. At once, the solid confines of cement and steel dissolve and we are inside nature, connected to the spirit of the earth, to the funky, musty smell of life and decay. Then Stamets, with the great contained energy he carries everywhere he goes, straightens and boards the plane to Delhi, taking the magic of the wild, and his hat made of coagulated mushroom mush, with him.

Stamets, the planet’s leading mycologist, was in India recently, a guest of the company Organic India. His purpose, besides introducing us to the Six Ways Mushrooms Can Save the World (‘the world’ including India of course), was to meet several top players involved in attempts to clean up the holy Ganga river. Stamets has many tricks up his sleeves to help clear the land, water and air of toxic waste, all involving mushrooms, and he is happy to share his knowledge for such a worthy cause. “Fungi are the basis of the health of our ecosystem,” he says, “they are miniature laboratories, deep reservoirs which store within them solutions beyond our imagination.” Stamets is quite sure that fungi are sentient beings—aware, intelligent and conscious of their purpose. “It has been proven in many prestigious studies. If we cannot recognise their intelligence, it is only because of our own limitations, not theirs,” he says, bright eyes twinkling though he is dead sober.

Lest someone doubt the seriousness of Stamets’ intentions, qualifications or capabilities, let us mention some of his achievements. He has proven that mushrooms are able to clean oil spills and turn toxic waste dumps into fresh, live soil; he has shown that they can break down nerve gas (and certain strains of mushrooms, shown to digest heavy metals, are being considered for use at the site of the Fukushima nuclear meltdown); together with his loyal team, Stamets has developed or is in the process of developing mushroom-based medicines against the bird flu and other viruses, malaria, E-coli, strep, pox, meningitis, Alzheimer’s, TB and cancer.

The American government, with which he has worked on several programmes, has given Stamets millions of dollars to further his research. He is in the process of developing a nano computer that uses mycelia—the underground living networks of long thin tendrils which are the actual body all mushrooms. Stamets has been awarded an unusually high number of patents in the US and elsewhere; recently he was awarded multiple patents on the making of any mushroom-based solutions against any known insect, an almost unheard of achievement and a potentially lucrative one. Stamets’ famous TED talk has been heard by at least 1.6 million people. And his books on mycology (the study of fungi) are considered the last word in the field. His subsequent TEDMED talk, delivered to an audience of over 800 physicians (often a sceptical lot) and the US Surgeon General, received a thunderous standing ovation; it introduced the value of medicinal mushrooms to the foremost thought leaders of the medical establishment.

Besides, and only slightly less exciting, is Stamets’ recipe which makes shiitake mushrooms taste exactly like bacon. “When people think about mushrooms,” he laments one day over our delicious lunch of daal and mushroom pulao, “they think of pasta sauce or maybe quiche. It is true that mushrooms are wonderful to eat, with more protein than any lentils or legumes and chock full of minerals, vitamins, immunity boosters and disease busters. Hey, I eat enormous amounts of mushrooms, and have not been ill in seven years. By the way,” he says, “never eat mushrooms raw.” If eaten raw, he says, their benefits are lost.

“I have a keen sense that we are living at the best of the last of times,” says Stamets later that night. We are basking in the peace of an Organic India farm on the outskirts of Lucknow, watching the moon rise over a Durga temple, surrounded by tulsi, brahmi and rose. “Things are more serious than we like to think, and time is less than we like to think. There is no doubt that we have entered 6X—the sixth planetary extinction level event. There are at present about 8.7 million species. A normal extinction rate would be something like 10 species a year. We are now losing 30,000 species a year—plants, insects, frogs, flowers. That is three million over the next 100 years. It is like losing the rivets on the body of an aeroplane. How many rivets can fall off before the whole structure is lost?”

Around us, the crickets pause, and a hush falls upon the garden. “We are still discovering new habitats and species, but as soon as we find them, they are lost forever.” “Cities like Shanghai and Beijing have committed ecological suicide,” he says. “If you would put a dome over those cities, I am afraid everyone inside would die of poisoning within 24 hours. Look at Delhi, at Mumbai…wonderful cities in many ways, but they are a blight on our ecosystem.” But, he says, there is good news. “We are part of this ecosystem, even if in our own minds we delude ourselves to think we are separate. The ecosystem will work through us, as it works through all of its members, it will guide us to find the proper solutions. But we need to listen.”

In Delhi, where others see only trampled earth, asphalt, cow dung, Stamets finds mushrooms. It is as if they call out to him by name. On a Saturday evening, an elegantly clad group of the city’s top physicians, scientists and lovers of the organic way gather at the Lodhi Hotel to listen to Stamets’ talk, munching all the while on mushroom samosas (with delicious tulsi pesto), tulsi iced tea, and macaroons and granola cookies in adorable mushroom shapes.

The host of the evening is Bim Bisell, the grande dame of Fabindia. Swami Chidanand Saraswatiji of Rishikesh, who is one of the leaders of the drive to clean up the Ganga, is present as well (the next day he, Stamets and Organic India’s leadership flew to Lucknow for a meeting with Uttar Pradesh Governor BL Joshi; Stamets introduced the—apparently viable—possibility of cleaning the Ganga with mycelial filters).

“I have many solutions for many of the specific problems facing India,” Stamets, in a necklace of turkey tail mushrooms made for this occasion by his wife, told the dazzled audience in Delhi. “First, the simple part: growing mushroom for food, we can get at least 50 times more protein per hectare than from raising animals, and mushrooms are nutritiously superior to legumes and lentils. Besides, we must understand that fungi are the gateway to unlocking the nourishment which is held inside of all matter. It is the digestion done by fungi which allows one organism to be nourished by another,” he says, “They are incredibly resilient to disease, which is why they make such good medicine; some of the most important medicines of all times are fungi/mushroom based… penicillin, of course, [the anti-cancer] cyclosprin, an immuno-suppressant used in transplants and one of the most successful drugs of all time, and, recently, Gilenya, for multiple sclerosis . But the potential has hardly been scratched. I would like to see community based mushroom centres throughout India—they would recycle, feed, decontaminate, rebuild soil by infusing it with moisture and nutrients, purify polluted water, build water reservoirs, and increase the biodiversity of every community. The mycelium is already there, under our feet at all times, but it needs our support to restore, replenish and regenerate itself.”

Stamets tells us of his mother’s miraculous, scientifically documented recovery from stage-four breast cancer using turkey tail mushroom mycelium. Stamets’ company, Fungi Perfecti (with its mission of ‘using gourmet and functional food mushrooms to improve the health of the planet and its people’) has a line of health supplements called Host Defense, soon to be marketed in India by Organic India.

There are, of course, questions to ask Stamets.

Can mushrooms really be intelligent? “The biggest problem with humans is their hubris in thinking that they know more than they really do; that intelligence can only be measured by our own yardstick. Indeed, I believe that all of nature is intelligent: if we are made by nature and if we are intelligent, then, by definition, nature must be so as well. I am sure nature is conscious of our presence as we walk through life. If we cannot see this, it only speaks to our own small mindedness; if we cannot hear nature speak to us, it is because we lack the proper communication skills. About mushrooms, specifically: there have been astonishing studies which have proven again and again that mushrooms know how to predict and adapt their behaviour to the future. They know how to calculate the most efficient way to achieve their goal; they build their networks in ways which have been confirmed by our highest technology to be mathematically optimal. These are all signs of intelligence.”

So not only can mushrooms save the planet, they also want to? “I propose to you that the mycelium is conscious. They are sentient. They are aware that you’re there. As you walk upon the earth, the mycelium reaches up and responds by grabbing the nutrients your footsteps have generated. There is a consciousness there, and we need to engage these intelligent organisms for our mutual benefit.”

This sounds a little like Avatar, doesn’t it? “I first proposed this in the mid-1990s, that mycelium is Earth’s natural internet, and I got a lot of flak for this. The structure of the mycelium is a vast neurological landscape which mimics that of computer networks and the internet. Because mycelia are organised as networks, they know how to survive catastrophes, re-grow and survive. They have so much to teach us. I really feel that these fungi have purposefully endowed me with their knowledge: they are working together with me, because I was ready to listen. Nature speaks to whoever really tries to listen. I guess you could call me a mycelial messenger.”

“I have always been attracted to that which is mysterious,” says Stamets, during a break between briefings and meetings, “mushrooms are mysterious. My parents warned me of them, told me to stay away, which of course only added to the attraction. Mushrooms, ephemeral, almost incomprehensible, elicit a lot of fear. They appear from nowhere, disappear in the flash of an eye; they can feed you, kill you, heal you, take you on a psychedelic trip which might change the way you see the world.”

And so they did for Stamets himself. As a child, Paul—who suffered from a debilitating stutter—was extremely introverted and shy. “I always looked down to the ground, avoiding eye contact. The last thing I wanted was to have to answer anyone’s questions.” He spent hours walking alone, eyes cast downwards; this is how Stamets and the mushroom found each other. As a young man, Stamets decided to try psilocybin, also known as ‘magic mushrooms’. Not knowing the proper dose, he ate too many and found himself up on a tall tree, seeing the world as he never had before, holding on for dear life as a major lightning storm wreaked havoc on the landscape. “I knew I might die,” he says, “and decided that if I didn’t, it was time for the stutter to be gone. I repeated this like a mantra throughout the many hours I was stranded in the intense, pouring rain.

When it was over, walking home, a cute girl who I had a crush on passed me on the street and asked me how I was. ‘I’m very well, thank you,’ I answered, and to both [her and my] astonishment, my words came out completely smoothly. My stutter has almost completely disappeared.” He says he did stutter when he met Bill Gates, though. “But wouldn’t you, too?”

Stamets, now a black belt in karate, lives with his wife Dusty Yao on the edge of the mythological redwood forests in the evergreen Pacific Northwest. On weekends, he, Dusty Yao, and his like-minded gang of employees frolic in the ancient mossy woods, searching for their fungal friends, challenging one another to eat hitherto unknown species (“If you get sick quickly, you have nothing to worry about. If you get very sick after 10-12 hours, then your mushroom was probably highly toxic”). Otherwise, when Stamets is not away at conferences or meetings with government sponsored researchers, he is busy with his staff at the company complex—where a vast collection of mushroom species reside side by side—developing new medicines, testing new pesticides, inventing cool products. His latest invention is a multi-award winning design for cardboard boxes that come with tree seeds and mushroom-based fertiliser already inside: just tear up the box and plant it.

Several years ago, as a community service, he and his colleagues laid sacks with specific mycelial content at the mouth of a local river which had been shut down for shellfish harvesting due to E-Coli contamination. Within a month, the river tested clean and the Health Department lifted its ban.

“I hear the voices of our descendants,” says the mycelial messenger, “calling back to us from the future, imploring us to wake up, asking us where the hell we were when something could still have been done. And so I try. I have had so many failures, but I just think of them as the cost of tuition. I have also had a few spectacular successes. I wake up everyday happy to be alive because I know my life has meaning as I do whatever I can to save as much life as possible on our gorgeous planet. I believe I have a real chance at making a perceptible difference. If I fail, at least I will die knowing I tried.” Below our feet, hidden beneath the soil, thousands of strands of mycelia—so delicate yet incredibly strong—spring up to greet us as we walk back home along the dusty path.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

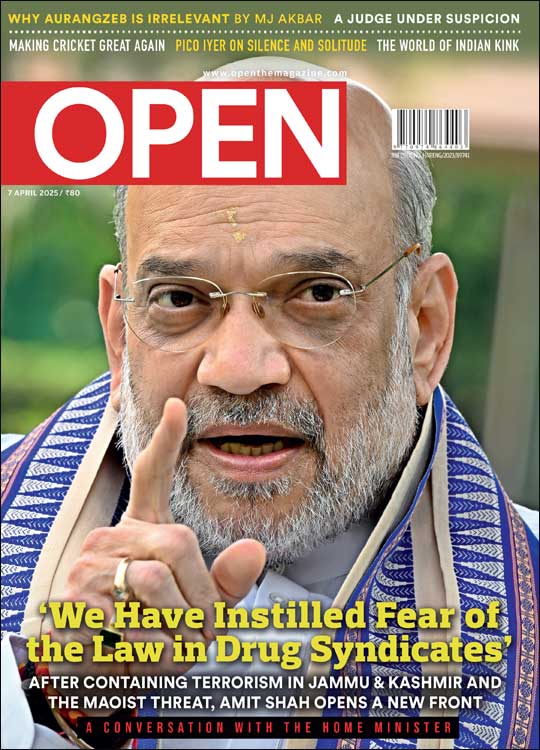

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

BJP allies redefine “secular” politics with Waqf vote Rajeev Deshpande

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh