Hardcell

What lies behind the hype of stem cell therapy in India

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

|

06 Dec, 2017

|

06 Dec, 2017

/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Stemcell1.jpg)

EARLY LAST YEAR, an orthopaedic surgeon in a distant Uttarakhand town who claims to be a stem cell expert announced an unusual project to revive the brain-dead. According to Dr Himanshu Bansal, who runs a small hospital called Anupam Hospital in Rudrapur, he was going to give 20 such patients a mix of therapies, from injecting their brain cells with stem cells and peptides which some say help regenerate grey matter, to deploying lasers and electrically stimulating nerves. He called it Project ReAnima. His aim, he said then, was to bring those in such a comatose condition to a minimally conscious state, where they might exhibit a few sentient signs of it like moving their eyes to track objects.

The news was met with outrage within the scientific community. Dr Bansal’s credentials in stem cell therapy, many pointed out, were questionable. And his proposed aim had several regulatory lapses. Although he had registered the trial with Clinical Trials Registry, he had failed to seek permission from the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI). “The whole trial was registered by mistake,” says Dr Geeta Jotwani, deputy director general of the Indian Council of Medical Research. The trial was de-registered and Bansal had to cancel his project.

But this was not the only questionable exercise he was part of. And it probably wouldn’t be his last.

Around the same time last year, Dr Bansal was part of a team that published a study in the Journal of Stem Cells, where they claimed to have used an experimental stem cell therapy to treat 10 autistic children aged four to 12. Dr Bansal didn’t respond to Open’s requests for an interview. There is no evidence to support stem cell therapy being effective in dealing with autism. Dr Bansal had extracted fluid from their bone marrow, based on his study, purified it into stem cells and re-injected these into their spinal canal. He claimed their conditions had improved.

The study had several gaps of credibility, let alone whether it should have been permitted at all. Among other things, there was no control group to compare the findings of the children undergoing stem cell therapy to those who were not, there was no mention of the ethics committee that had reviewed the study, nor any attention paid to potential conflicts of interest. Dr Bansal and another researcher were also part of private ventures that provide—and stand to profit from—stem cell therapies. Most credible journals have guidelines that address such issues. Another anomaly: one of the researchers was also listed as editor-in-chief of the journal.

“There is a simple answer for journals like that—predatory,” says Dr Aniruddha Malpani, an IVF specialist in Mumbai. “They will publish anything [for a fee].” The phenomenon of predatory journals is rampant in Indian science academia, where dubious journals imitate the appearance of highly regarded scholarly publications and claim to have a rigorous peer-review structure, but in reality, as long as you pay, you can get anything published.

There is a dubious but flourishing industry around stem cells in India. There are doctors who have established successful practices selling hope, offering unproven and even dangerous stem cell therapies for conditions and disorders that are currently incurable, from autism and cerebral palsy to spinal cord injuries. Some argue that even large stem cell banks in the country are no better.

The promise of stem-cell research lies at the heart of our desire to cheat death and lead long healthy lives. Stem cells first broke into the public consciousness back in the 1990s, as a way to use live material drawn from a person’s own tissue for his or her treatment. Since it involved using patients’ own stem cells, we were told, it could deliver new treatments for a range of diseases, fighting back degenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s, for example, or growing new internal parts to treat conditions like spinal cord injuries, maybe even regenerating whole organs from a few cells.

The field was revitalised in 2006 when the Japanese scientist Shinya Yamanaka, who later won a Nobel Prize, devised a technique to ‘reprogram’ any adult cell and coax it back to its earliest ‘pluripotent’ stage. From there, such a base cell can become any type of cell.

But the onward march has been slow and halting. Researchers are still learning about stem cells, how best to use them, what types to use and even how to deliver them safely into the body. “There is a lot of hype around stem cells. It is looked as something of a miracle,” says Krishnamurthy Kannan, stem cell expert and biotechnology professor at the Indraprastha University in New Delhi. “The truth is that stem cells might be the answer to all these diseases, but we are all a long way away from that.”

The Government is now making an effort to regulate this industry. The ICMR has issued guidelines to curb what it calls ‘rampant malpractice’. It has listed out a few conditions, mostly blood and immune related, in adults and children where stem cell therapy is permitted. All other commercial use of stem cells ‘as elements of therapy’ has been banned and erring clinicians have been warned of punishment. “We are only committed towards treatments that have proven efficacy. Stem cell use in patients, other than that for treating approved hematopoietic [blood] disorders is investigational at present and can be conducted only in the form of a clinical trial,” Dr Jotwani says.

The guidelines also state that stem cell banks are allowed to store only stem cells from umbilical cord blood and no other biological material. Most such banks in India otherwise store stem cells from a variety of biological sources, from umbilical cord blood and tissue to placenta, tooth extract, dental pulp, adipose tissue and menstrual blood. “Why should they store this?” Dr Jotwani asks. “There is no evidence that any of this has any benefits.”

“What’s happened is that the authorities are trying to prevent misuse of stem cell treatments. The utilisation is the problem, not the banking of stem cells. They should be focusing on that” – Dr Mayur Abhaya, MD & CEO, LifeCell International

MAYUR ABHAYA IS CEO and managing director of LifeCell International, the largest stem cell bank in the country. There are several private and public stem cell banks in India, but his company claims to have more than half the market. It has so far preserved stem cells from more than 270,000 individuals, including the children of public personalities like Aishwarya Rai-Bachchan.

According to Abhaya, stem cell banking is still in a nascent stage in the country and there is immense potential for its growth. “India is the largest birthing country in the world. The next country, China, is far behind at this,” he says. “Every year some 100,000 new people opt for stem cell banking. And we get around 60,000 [of them],” he says.

To popularise the concept, he says, the company has managed to enlist the help of over 12,000 doctors in more than 4,000 hospitals across the country. “We are present in more than 150 cities here. When we start a new centre, we look for places with a population of at least one million people,” he says. LifeCell offers gifts and free ‘babymoon’ holidays when parents chose to preserve cells, and even an option to pay in EMIs.

LifeCell recently changed its business model from a purely private stem cell bank, where a member could access his stem cells when needed, to BabyCord Share, a community stem cell sharing bank, where all members and their immediate relatives can access a pool of stem cells from those who opt for this community model.

Ailments such as thalassemia and leukemia, for instance, require stem cells from donors. By allowing sharing, Abhaya says, individuals are covered for a wider number of conditions. Around 10,000 people have already opted for this new model, and Abhaya expects more, including the existing units stored in the bank, to upgrade to this new scheme. “It’s a no-brainer really. You get coverage for more conditions, and also your siblings, parents and grandparents,” he says. “LifeCell’s growing inventory provides you the best chance of finding a matching donor unit for all conditions treatable by stem cells.”

Dr Jotwani points out that unless there is a history of certain ailments in the family, where the cord blood of one child can benefit an older sibling treatable by stem cells, there is no pressing need for people to preserve their stem cells. “The benefits, if any, are quite limited right now. And these banks have realised that and some of them you see are changing their business model to allow sharing among people,” she says.

One of the issues, experts point out, is the manner of its marketing. Stem cell banks often issue misleading advertisements about the likely benefits of stem cell preservation. “Every parent who delivers in an upmarket hospital today is told by their doctor to store their baby’s stem cells. The marketing spiel is that it’s a very cost-effective investment for their baby’s future. That these stem cells are so precious and can be used to replenish any kind of cell in the body in the future,” Dr Malpani says. “They play on the parents’ guilt. These stem cell banks induce the obstetrician and the hospital to sell this concept when stem cell banking is so expensive and unproven.”

Many of these hospitals, as Dr Malpani points out, organise antenatal classes and baby showers prior to delivery with the support of stem cell banks, so that the banks can pitch their services to expecting parents. “These antenatal classes appear innocent. But they are rally programmes for customer acquisition,” he says. “And we have no idea, if ever a patient were to need his stem cells, how good the facilities are, how well they are preserved.”

ACCORDING TO DR JOTWANI, the importance of stem cell banking can be judged from the number of people who eventually used the stem cells preserved in these banks. LifeCell, Abhaya claims, has released about 50 units from its bank of over 270,000 stem cell units since its 2004 inception.

LifeCell, for instance, preserves stem cells from cord blood, cord tissue and menstrual blood, running afoul by the new ICMR guidelines, which allow the storage of only umbilical cord blood stem cells. According to Abhaya, people should have the right to preserve stem cells taken from all biological sources. “There are many scientific research [studies] and clinical trials involving these stems going on all around the world. Who is to say these won’t be beneficial?”

LifeCell has objected to the ICMR’s guidelines and asked for a review. “What’s happened is that [the authorities] are trying to prevent misuse of stem cell treatments. The utilisation is the problem, not the banking of stem cells,” Abhaya says. “They should be focusing on that.”

Dr Geeta Shroff runs NuTech Mediworld, a successful stem cell therapy clinic in Delhi. An obstetrician and infertility expert by training, she now focuses on stem cell therapies. Her clinic is filled with patients from several countries— she claims to have treated more than 1,500 patients from more than 52 countries since the early 2000s—from children with disorders such as autism and cerebral palsy to adults suffering from spinal cord injuries, Type 2 Diabetes and Parkinson’s. The disorders and ailments she claims she can cure with her stem cell therapies are many. “I am very often the last hope for these people,” she says.

Her treatment comes in the form of packages, ranging from a single week to up to 12 weeks. Each week—and this includes meals, boarding and nursing charges—costs between $5,000 and $6,000.

Dr Shroff claims to treat patients by administering them with embryonic stem cells. Most other clinics claim to treat patients with adult stem cells derived from their own bone marrow or those of donors.

Embryonic stem cells come from 4 or 5 day-old fertilised eggs. These cells are controversial because they are harvested from leftover IVF embryos, which are destroyed in the process. But they are special because they potentially have the ability to turn into any type of cell in the body. Since 1998 when researchers first managed to derive and culture human embryonic stem cells, they have been trying to coax these unique cells into becoming cells for every part of the human body, and thereby hopefully someday help repair bodily damage or regenerate tissue.

According to Dr Shroff, she managed to develop endless lines of embryonic stem cells from a surplus egg (embryo) she received from a female patient (with her consent), who was undergoing IVF treatment several years ago. She claims to have developed the technology to isolate embryonic stem cells, culture them, prepare them for clinical application, and store them in ready-to-use form with a shelf life of nine years. They are administered in a variety of ways, from injections to nasal sprays and eye drops.

Dr Shroff has published some studies showing the efficacy of her work, but most of them have appeared in non-peer-reviewed journals, say experts. “The big question is, what is she injecting people with? It’s not embryonic stem cells for sure,” says a researcher requesting anonymity, adding that Dr Shroff hasn’t allowed sceptics or authorities access to her labs.

Many of the conditions she offers treatments for now run afoul of ICMR’s latest guidelines, according to which, in these cases, therapy can only be administered as part of properly-approved clinical trials. “It’s great what the ICMR is doing, bringing about modernity in guidelines. We’ve been a bit behind otherwise… I’ve always followed all the rules,” says Dr Shroff. According to Dr Jotwani, the Drugs and Cosmetics Act is being amended and soon doctors found guilty of violating stem cell therapy and banking guidelines will be punished.

What about the ban on the commercial use of stem cells for any treatment other than proven procedures? “You have to understand these are only guidelines,” Shroff says. “They are not hard law.”

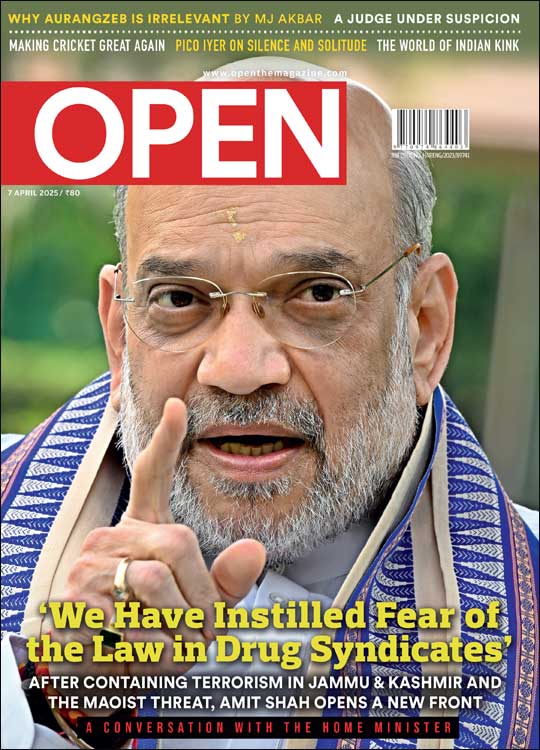

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

A Freebie With Limitations Madhavankutty Pillai

Calling Japan Kaveree Bamzai

Knives Out in the White House Kaveree Bamzai