Budget 2019: A Class Act

Modi regains the political momentum

Swapan Dasgupta

Swapan Dasgupta

Swapan Dasgupta

Swapan Dasgupta

|

07 Feb, 2019

|

07 Feb, 2019

/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Budgetanalysis1.jpg)

Whereas the middle classes were mildly rooting for Modi as elections approached, the Interim Budget has ensured they will once again go all out for him in 2019. The Budget has converted passive support into active enthusiasm which will only increase as they look upon the possibilities of a coalition dominated by Mayawati, Mamata Banerjee and the sons of Lalu Prasad Yadav with trepidation and fear

AN INDIAN GENERAL Election is comparable to a marathon. Stamina and the ability to keep a steady pace are no doubt indispensable. However, the final few miles necessitate tactical planning: steady nerves and, above all, reserves of strength for the final dash.

In theory, heightened excitement for the 2019 General Election will begin with the Election Commission triggering the Code of Conduct that, in effect, ties the hands of the elected Government—except, perhaps, in times of war, as happened in 1999. The frenzy will mount with the candidate selection process that also witnesses many political crossovers. And finally, there is the final round of frenetic campaigning when politicians of all sides muster all their reserves of strength, imagination and acumen.

The starting point of this year’s General Election was, unquestionably, the Assembly elections of November- December 2018 that led to the BJP losing control of three important state governments in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan to the Congress. Except for Chhattisgarh, where the Congress romped home quite comfortably, the battles in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh were closely contested and although the Congress prevailed, the BJP was by no means decimated. In terms of popular votes, both the Congress and BJP were evenly matched.

In the post-mortem of the election, the BJP attributed its disappointing results to three factors.

First, there was discontent among farmers over the lack of adequately remunerative returns from agriculture. The announcement in the 2018 Union Budget that the Minimum Support Price of selected agricultural produce would be 1.5 times the production costs hadn’t fully translated into reality, leading to both disappointment and anger.

Secondly, there was unease among a section of urban voters over hiccups of the 2016 Demonetisation and 2017 introduction of the Goods and Services Tax. The most affected was the trading community—traditionally loyal supporters of the BJP. Accustomed to conducting their business in cash and below the tax radar, they were unsettled by both the reduction in the cash economy and being catapulted into the tax net. What made a bitter experience even more disquieting was the fact that their forced entry into the modern, organised, tax-paying sector had been forced by their very own party, the BJP. This sense of apparent betrayal cost the BJP crucial urban seats and made all the difference between winning and losing.

Finally, there was a bitter reaction among upper castes over the Centre’s legislation strengthening the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act. The move had been occasioned by a Supreme Court judgment stating that an FIR relating to any allegation under this law had to be preceded by a preliminary inquiry. Although the Narendra Modi Government had no hand in this apparent ‘dilution’ of the original law by the apex court, it was accused by Dalit groups of being complicit in the move. To offset this impression, the Government was compelled to bring in an amendment restoring the original law in the Monsoon Session of Parliament last year. This in turn provoked an upper-caste backlash that, combined with the demand of certain dominant rural communities such as Rajputs, Jats and, earlier, Patidars in Gujarat, destabilised the delicate caste equilibrium the BJP had maintained. Consequently, for really no fault of its own, the BJP lost a small but important slice of its assured vote.

Politically, the BJP’s defeat in the three state Assembly elections coincided with two other significant developments.

The government’s principal focus was the farming community that felt short-changed by the lack of remunerative returns from agriculture

First, a beleaguered opposition, shaken after its decimation in Uttar Pradesh in 2017 and the small state of Tripura the following year, finally woke up to the realisation that they had to hang together for the sake of survival. The victory of the Samajwadi Party-Bahujan Samaj Party alliance in three by-elections to the Lok Sabha (including Gorakhpur that had been won uninterruptedly by the BJP since 1989) was not only a morale booster, but a pointer to the road ahead. Consequently, with N Chandrababu Naidu and Mamata Banerjee adding their weight to the cause of a grand anti-Modi alliance and the Congress under Rahul Gandhi showing a greater sensitivity towards erstwhile non-BJP opponents, the stage was set for a concerted challenge to a BJP that, till mid-2018 at least, seemed unbeatable.

Secondly, the cumulative effect of the opposition gang-up and the defeats in the Assembly elections was felt at the level of perception. There has always been a formidable anti-Modi constituency in India, but it suffered from dispiritedness. An important section of the media and almost the entire intelligentsia had never reconciled themselves to Modi and were unrelenting in their opposition to him. However, this opposition was simultaneously marked by a feeling of hopelessness and the belief that the public mood had swung too far to the right. The UP Assembly election of 2017, which the SP-Congress alliance genuinely hoped to win, particularly after Demonetisation, was the biggest shocker. But the mood changed abruptly after the by-election victories. This was more so because the BJP went into a state of shock and lost control of the political narrative. In hindsight, its approach to the Assembly elections was marked by the absence of the cadre enthusiasm normally associated with the party. There was a perceptible sense of drift, although tempered by a simultaneous belief that Modi would somehow wave his magic wand and set things right.

What really distinguishes Arun Jaitley from Piyush Goyal as finance minister is Delhi and Mumbai. Jaitley, an extremely successful lawyer, viewed his charge of the finance ministry as a macro-economic responsibility. For him, it was gross domestic product and fiscal responsibility that were paramount. Goyal, an equally successful chartered accountant in Mumbai, had a slightly different view of priorities. He as concerned more with personal finances and relatively less with macro-economics

The BJP’s fightback started in right earnest with the 10 per cent reservations for the economically disadvantaged among non-reserved castes and communities. The move was sudden but it was rushed through Parliament with a determination that hadn’t been in evidence since 2017. At one stroke, the Constitution Amendment achieved two things. First, it addressed the feelings of injustice that had been steadily accumulating among upper castes and those middle castes that felt cheated out of both political power and government jobs. It may be premature to rush to conclusions, but after the passage of the new system of reservations, various burgeoning caste movements have lost momentum. Secondly, the new quota policy lowered opposition to special protection for Dalits and tribals. In short, the BJP succeeded in addressing part of the concerns of those voters who seemed ready to desert it in 2019.

The Interim Budget of 2019 has to be viewed in this backdrop— as part of the BJP’s attempt to shake off the disappointments of the past six months and regain the political initiative once again.

THE GOVERNMENT’S PRINCIPAL focus was the farming community that felt short-changed by the lack of remunerative returns from agriculture. In the past, the Modi Government had attempted to address rural concerns with heavy investments in rural infrastructure, notably rural roads and irrigation. This was complemented by special schemes targeting women—subsidised cooking- gas connections and the construction of toilets, both aimed at improving the quality of life. The Ayushman Bharat health scheme—which is still a work-in-progress—also addressed an important healthcare concern. However, the issue of more cash in the pockets of poor farmers remained unaddressed.

Ironically, it was the electrifying effects of Rahul Gandhi’s announcement in Chhattisgarh of dramatically raising the Minimum Support Price of wheat with immediate effect that showed the way. The Centre has announced that it will increase the MSP to 1.5 times the cost of production, but there is likely to be a gestation period between announcement and delivery. Moreover, the biggest beneficiaries of increased MSP are farmers with relatively large landholdings. The boost for small and marginal farmers is significantly less for the reason that they have less of a marketable surplus.

Whether the scheme to give every small and marginal landholder a direct annual payment of Rs 6,000 in three equal instalments will be a game-changer still belongs to the realm of speculation. Activists, quite predictably, have debunked the scheme as being a case of too little too late. That may well be the case. But two things need to be considered. First, that by the time rural communities queue before the polling booths in April and May, they may well have received Rs 4,000 in their bank accounts. Secondly, unlike many welfare schemes that suffer from confusion over ownership—whether funded by the Centre or the states—the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi is going to be funded entirely by the Centre. This means that petulant chief ministers such as Mamata Banerjee will not be able to get their states to either opt out of the programme or claim credit for it. If cleverly implemented, this will unambiguously be a Modi bonanza. Even if it doesn’t swing votes, it will certainly dilute the visceral anti-Modi message the opposition parties are going to unleash on voters.

Not since the Rajiv Gandhi government abolished death duties in 1986 has the propertied middle class been given such a lollipop

The second facet of the Interim Budget that stemmed from political concerns was the targeted wooing of the middle classes. Unlike the Congress that combines an elite leadership with a social base that is made up of the poor and minorities, the BJP’s social centre of gravity has always been the country’s middle classes. This is the section of the electorate that is most attracted to Hindu social authenticity and which combines conservatism with upward mobility. It has always stood by the BJP, and the success of the party in elections has traditionally depended on the magnitude of its commitment. The more solid the commitment, the more the BJP is able to percolate its reach down the socio-economic ladder.

That there was some disappointment with the BJP is undeniable. Part of that stemmed from Demonetisation and GST, but among the salaried and professional classes the unease stemmed from the high expectations that the middle class has of the Modi Government. To them, ‘achche din’ (better days) meant greater opportunities for business and entrepreneurship, it meant low taxes and greater opportunities for accumulation, and it meant pride in being a global Indian.

It is not that the Government was insensitive to these aspirations. Over four years, the Modi regime kept taxes stable and low, didn’t introduce death duties, made tax compliance easy and considerably improved the ease of doing business. However, it kept its middle-class thrust carefully concealed, preferring, for obvious political reasons, to showcase its rural thrust. After Demonetisation—which inconvenienced the middle-class considerably and depressed the real estate market—its rhetoric was outright populist. Finally, it was unrelenting in pursuing tax avoidance, something that unsettled a section of the business community.

After the Interim Budget, the BJP believes it is back to its winning ways. It believes that it has reclaimed the political narrative. The swelling crowds for the Prime Minister, it feels, are indicative of five more years

IN SUM, THE direct benefits to the middle class from political stability, low inflation and assured, low tax rates were smoked out by a messaging that made it seem the BJP had downgraded its most loyal and steadfast supporters.

This Budget was the occasion to set those signals right. It was principally targeted at the party’s lower middle-class supporters, those earning Rs 1 lakh and below who needed extra cash to accommodate their soaring aspirations for a better life. However, perhaps for the first time for any government, it also took into account the concerns of those slightly higher up on the economic ladder—those victims of Demonetisation and GST who had been dragged reluctantly into paying taxes.

What really distinguishes Arun Jaitley from Piyush Goyal as Finance Minister is Delhi and Mumbai. Jaitley, an extremely successful lawyer, viewed his charge of the Finance Ministry as a macro-economic responsibility. For him, it was Gross Domestic Product and fiscal responsibility that were paramount. Goyal, an equally successful Chartered Accountant in Mumbai, had a slightly different view of priorities. He was concerned more with personal finances and relatively less with macro-economics. This may explain why the Interim Budget contained the pathbreaking proposal to exempt people with a second residential property from being taxed on a notional rental income, and being spared capital gains on its once-in-a-lifetime sale and reinvestment. By this single gesture, Goyal has ingratiated himself with a class that never imagined that their concerns would ever be addressed, except negatively. Not since the Rajiv Gandhi Government abolished death duties in 1986 has the propertied middle class been given such a big lollipop.

It is the delight of the middle classes at having been finally acknowledged as a force in politics that is responsible for the post-Interim Budget euphoria in the BJP ranks. Whereas the middle classes were mildly rooting for Modi as elections approached, the Interim Budget has ensured they will once again go all out for him in 2019. Goyal’s Budget has converted passive support into active enthusiasm for the BJP. It is my belief that the enthusiasm will only increase as they look upon the possibilities of a coalition dominated by Mayawati, Mamata Banerjee and the sons of Lalu Prasad Yadav with trepidation and fear.

After the Interim Budget, the BJP believes it is back to its winning ways. It believes that it has reclaimed the political narrative. The swelling crowds for the Prime Minister, it feels, are indicative of five more years. The challenge is no less formidable, but at this stage of the marathon, the incumbent is brimming with energy and confidence.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

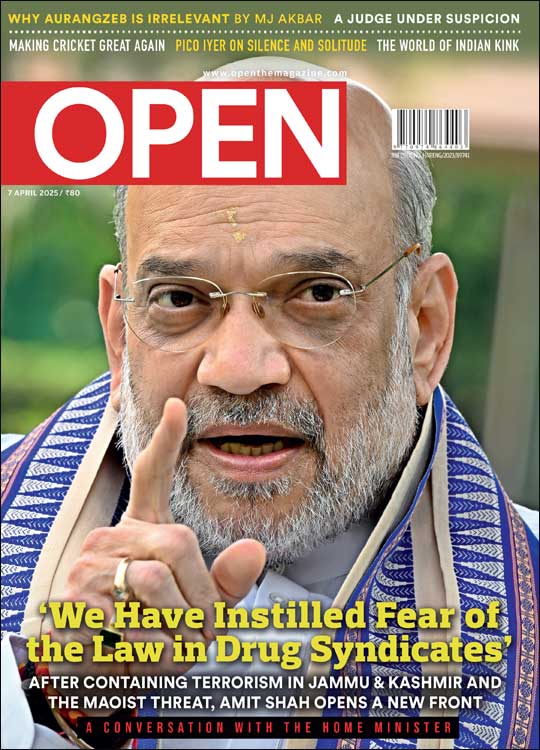

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

BJP allies redefine “secular” politics with Waqf vote Rajeev Deshpande

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh