Rahul Bhatia: High Flier

The man who runs Indigo, India's most successful airline. A portrait

/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/18374.highflier1.jpg)

As you motor up the driveway to Rahul Bhatia’s home, you instantly sense that IndiGo, the company he built from scratch, could not have been owned by anybody else. His farmhouse on the road to Jaunapur village in South Delhi is a muted merger of the urban and pastoral, the urbane and the basic, an artistic composition blending seamlessly the austere and the elegant. No gold-plated name board marks the living quarters of the head honcho of India’s most successful airline business, no intimidating security platoons cavity-search a visitor, no liveried minions dot the driveway leading to the front entrance, no dancing maidens materialise out of nowhere, no cologne-soaked hangers-on overwhelm you as you enter the living room. Works of Indian masters adorn the walls; the chintz upholstery doesn’t scream as you sink into one of the sofas. You enjoy the sight of green lawns beyond the huge picture windows while you wait for India’s most powerful aviator.

So, he isn’t that in-your-face industry hotshot who sandblasts his way into news space by flying in a hot air balloon across the world or launching an inter-galactic space tour company. Or elbows onto Forbes’ global list of billionaires with a luxury game reserve and two private islands making for a fine photo op. Bhatia, the man who launched InterGlobe, the holding company for India’s best known and most profitable airline, IndiGo, is the anti thesis of Virgin’s Sir Richard Branson. No myth-making stories of singlehandedly slaying Goliaths or dedicatedly studying under a streetlight to make it to where he is today. No brash images of living the vida loca, beautiful women wrapped all around him. He is, if you will, a simple, defining haiku note to Vijay Mallya’s high-pitched vaudeville and much-eyeballed centrefolds.

The closest you get to a tellable fable is from a time towards the end of 2011, when this managing director of InterGlobe, along with President Aditya Ghosh, drove up in a humble CNG-powered Wagon R emblazoned with the duotone hues of IndiGo to the Prime Minister’s Office for a meeting of aviation bigwigs over an industry crisis with then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Ghosh later said in an interaction that, one, IndiGo didn’t have big cars, and two, of the three available choices of transport that day, the Wagon R, which had the company colours and was a great car to boot, was the best available option.

If the other CEOs, who arrived in chauffeured bling bling dream machines, were of the opinion that Bhatia was an inverse snob, they tried not to show it openly. But in the months that followed, they did make it clear that he didn’t quite make the notch in their book of People Like Us. That mistrust, truth be told, had a back story of sorts. In mid-2009, about three years after IndiGo’s launch, all private airlines decided to suspend services in protest until the Government rolled back high aviation fuel taxes. Initially, the suspension was to be for a day, under the baton of Jet Airways’ Naresh Goyal and Kingfisher Airlines’ Vijay Mallya. But hours after the decision, IndiGo backed out, followed by SpiceJet, thus easing the pressure on the Centre to lower the taxes. Add to that the little fact that IndiGo, even through those tough times, appeared to be doing okay compared to the biggies of the time such as Jet and Kingfisher. Little wonder then that Bhatia didn’t make it to the Indian aviation industry’s Most Popular list. And perhaps still hasn’t, going by the Twitter attacks of both Mallya and Air Asia’s Tony Fernandes in more recent months. But if passenger numbers are any indication, IndiGo is right up there, more popular than the rest, where it really counts.

He arrives quietly, without fanfare, within seconds of my arrival. Dressed in a simple linen shirt and black trousers, a tall man with an easy way and almost shy smile, looking every inch cool and at home. “You are right on time, like IndiGo,” declares the 53-year-old as we shake hands. No godly figurines tower over us in the room, but Bhatia is clearly a believer. At least, that fortune favours the good, especially after his stunning success in one of the most unpredictable segments of the aviation market in the world.

IndiGo was the only airline to make a profit in the low-cost aviation segment during 2011-12 and 2012-13, a period marked by high fuel costs and immense churning. It is even today the unlikeliest of mascots for Indian aviation: ploddingly patient if ambitious, understated, muted, quiet. And Bhatia is a man who cultivates the image of an Average Joe with a touch of obsession even as his airline, India’s largest, soars in popularity among passengers and IndiGo prepares to launch an Initial Public Offer of its equity shares to raise around Rs 2,500 crore from investors this fiscal year. “He had immense patience. That’s one singular quality I recall about him,” says a former official in the AB Vajpayee Government that gave Bhatia the licence to fly. “He would sit for hours and wait for a brief meeting with ministers or other officials without fretting and fuming.”

So, if he weren’t the top flier of the Indian aviation industry besides the man behind the biggest hospitality group—8,000 rooms in all—in the country, how would he have turned out? He replies without a pause, somewhat wistfully. “In the 1980s, after my digital switches venture took a nosedive, I wanted to get a post-grad degree and start teaching,” he says, “The attraction of teaching was that you were the master of your own time. Professors in universities own their time. Forty per cent of their time is spent on teaching and the rest on doing research. I was fascinated.”

Some of the key men he relies on at IndiGo vouch for how good a teacher their boss is. Aditya Ghosh, for example, was an advocate by profession and a complete aviation rookie when Bhatia and his partner (and one- time United Airways man) Rakesh Gangwal picked him; today, Ghosh is an airline chief that other CEOs in the industry would gladly trade places with. Bhatia’s working style is one that appears to inspire trust as much as awe. “If Vijay Mallya is a control freak who prefers to hold all the reins in his hands, Bhatia believes in delegating authority and work and backs that with full faith,” says an industry observer. The attitude has a ripple effect. Ghosh, for instance, meets all employees at least once a year and is known to personally suss out everyone his company hires, including mechanics and technicians.

It soon becomes clear why the man who owns the country’s favourite airline—notwithstanding its decision not to run a points-based loyalty scheme like rival airlines—looks and sounds so at ease with the tranquil surroundings. “I am basically a Delhi boy and studied at Modern School on Barakhamba Road. I was born in Nainital, where my family used to spend their summers. And right after school in 1977—which incidentally was the last year of All India Higher Secondary Board—I went to Toronto to get my undergrad degree in engineering at the University of Waterloo.” Bhatia confesses that he had little clue of what he wanted to do at the time, but chose engineering mainly to please his mom, whom he adores. He graduated as an electrical engineer and even made it to the Dean’s Honour list.

When he returned to Delhi, it was a watershed year: 1984. Indira Gandhi had been assassinated, and the nation’s well-being looked precarious. Communication had broken down completely for nearly three days in several areas of the capital where rioters went on a rampage against members of the Sikh community, butchering many before the rest of the city even came to know of it. With Rajiv Gandhi at the helm, telecom then became the new buzzword. The young Bhatia clinched an arrangement with Northern Telecom (Nortel) to make digital telecom exchanges. But Prime Minister Gandhi had other plans for the sector, with poster boy Sam Pitroda piloting a revolution in the communication sector across the length and breadth of the country. “The Government wanted to develop indigenous telephony through C-DoT.” Bhatia’s deal with Nortel eventually witheredaway. (It’s worth finding out what CDoT did over the years. Incidentally, CDoT is housed in a building close to Bhatia’s farmhouse.)

The turning point came in early 1988, when a setback in the digital switches business eventually opened up new opportunities for Bhatia—first in the travel business and then in civil aviation. “My dad in those days was running a travel company—what people call a GSAS,” he recounts, “They were representing various airlines in India. It had several units, and the flagship was Delhi Express. I had a very reluctant initiation into that business. It was not something that I was educated for, probably not something that I wanted to do…”

But then, his dad Kapil Bhatia became unwell. In a sense, it forced his hand. “One day we sat together and he told me that my heart is not in what I do.” That wasn’t an admonishment, however. Bhatia Sr agreed to encash his equity in the business so that his son could do whatever he had set his heart on. The father’s road to Delhi had been a hard one that ran through Lucknow from Rawalpindi, and it wasn’t an easy decision. “I couldn’t say ‘no’ to him,” Rahul Bhatia recalls. But the business had some structural problems. His father had managed to get nine of his friends to pool in Rs 11,000 each as startup money, and with another Rs 1,000, they had a capital base of Rs 1 lakh. Since he had no money of his own to put in, his share of the business—there were 10 partners with 10 per cent equity each—was what’s now called ‘sweat equity’, for putting the business model together and executing it.

When Bhatia decided to join his father’s business, he had a feeling that it had structural issues. “I did share my apprehensions with my father. If someone wanted to get him out of the job, it was easy to do. But he did not agree with me. He had run this business for almost 25 years and had lulled himself into believing that nothing of that sort would happen.” Bhatia says as things turned out, in late 1988, 50 per cent of the initial ownership of Delhi Express got passed on. “Exactly what I said came true. My dad was ushered out of the company.”

That bitter experience led to the formation of InterGlobe, a travel services firm. “On paper, it was formed on 6th of October, 1989. I will not forget the date because October 6th happens to be my wife’s birthday,” says Bhatia.

The initial days were difficult for the father-son duo. “One question that is often asked is about our initial capital in the business. If I remember correctly, it was… whatever was the exchange rate at that point, multiply it by $140,000. That was all the money that went into the business. That was all we had,” he says. This meant little infrastructure and very little business. “Our first office was at 66 Janpath. It was where United Coffee House stood.”

The first few years were tough going. But some of the airlines that worked with the previous company were willing to switch allegiance to the new entity, Inter Globe, to sell flight tickets. “In those days, one institution that was willing to help us was the Bank of Tokyo, which is now Mistubishi something.” Every two weeks, to keep up with the payment cycle that airlines wanted, Bhatia would go to the bank and seek funds. And that went on for some time. In 1994, he got the distribution franchise for what is then known as Galelio International. “On occasions when I have nothing better to do, I spend time reading that contract with Galelio. It was a business that we did not understand. The reason that it came to us was because we had a relationship with United Airlines. And United owned 40 per cent of Galelio. They came and told us that they want to put out their product in India. I was so paranoid that we put in a clause which said that at any given time, if our cumulative losses in that business were to cross the mark of $400,000, we’re out of it. ‘Take your franchise back, we are done’.”

By the mid-90s, life started getting better. “Of course, my folks would say that I was on the road most of the time in those days trying to find new opportunities,” he says with a smile.

In 1999, Bhatia set up an infotech services business with Galelio because the latter had captive needs. “Life went on, but there was this itch to go on to an airline,” recounts Bhatia. “But it was only a dream because I had no resources.”

In 2002, a close friend of his father met him in Hong Kong to sound him out about a French hotel group called Accor that owned a three-star plus brand called Ibis Hotels and wanted to expand in India with an eye on middle-class spends. It had earlier partnered with Oberoi, then with Mahindra, and later a Kolkata-based company, but was looking for a new partner. Accor’s first property was in Agra (now the Trident). A meeting was called. “They were keen to work in India, but they were looking for a new partnership. They believed in the opportunity because they believed in India and its growing middle-class. The middle classes want value for money. I said in principle: ‘It’s okay.’ We closed the deal in November 2004.”

And so InterGlobe embarked on a new journey of setting up hotels. Initially, it was mainly Ibis, in partnership with Accor. But over time, the company not only set up hotels with it under the Ibis brand, but also Novotel and Pullman (an upscale chain of hotels for business and leisure). A joint venture was set up to develop a network of Ibis-branded hotel projects throughout India, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh. In January this year, there were some reports of discontent between the French hospitality major and InterGlobe Enterprises over upcoming hotel projects. Accor had tied up with another company to build Formule 1 hotels despite an existing deal with InterGlobe. Subsequently, though, Accor issued a statement saying that InterGlobe remained a strategic partner of Accor in India for a variety of projects. For its part, InterGlobe said it had no plans of exiting any of the properties.

Today, InterGlobe’s Accor portfolio accounts for 8,000 rooms in India. “We have two joint ventures with them. One joint venture is an asset JV where we own the properties and then the management company manages them. Second, we have a management company which manages even third-party properties. It is an interesting business. It is going to be the largest lodging portfolio in the country,” Bhatia declares.

An acquaintance who has attended some of the parties that Rahul Bhatia has thrown contends that this is one aviation industry honcho who keeps Page 3 types strictly at bay, unlike some more glitzy members of the club like Mallya, who flaunts his penchant for living it up even as his employees go unpaid for months. “Most of those who are invited are people [that Bhatia] has known for ages and vibes well with. There are no garish notes, and the atmosphere is always convivial, with a high comfort level,” says the acquaintance.

Among those friends was Rakesh Gangwal, formerly with United Airlines. “We go back a long way,” Bhatia says, avoiding the common Delhi pitfall of ‘old friends’. ‘When Bhatia Met Gangwal’ could be fluffed into an epic novel of its own. The latter was still at United when Bhatia was introduced to him. Through the Ibis-Accor years, he continued to nurse the fledgling dream of setting up an airline business as a sort of companion piece to his travel and hospitality interests, a dream that assumed vividity after the introduction. “So the itch of the airline continued… but there were no ‘sponsors’ within this family, among friends or well wishers. Almost everyone used to warn me that an airline business would take the Mickey out of me,” says Bhatia.

The dream began to evolve and take clearer shape as Bhatia and Gangwal got to know each other better. “We’ve been friends since the time we were first introduced. I was certain, after meeting him, that if I ever entered the aviation business, I wanted him as my partner. Not least because of his experience and background. Initially, he wasn’t very keen. He used to say that the dream would break my back,” Bhatia reminisces.

But Bhatia was determined not to take ‘no’ for an answer. Gangwal’s experience, he was sure, would come in handy in setting up a low-cost carrier in India. Finally, he was able to get him on board by the end of 2004. Together, they rolled up their sleeves and worked on the drawing board that would kickstart the realisation of the airline dream. In 2005, even before the company was launched, they made news by placing a huge order for their first set of 100 Airbus A320 aircraft. Bhatia thought ‘IndiGo’ was a perfect name for the new airline because it evokes two things simultaneously: India and being on the go.

The new bird on the block was launched in 2006, based on the sale-and-lease-back model adopted by America’s Southwest Airlines, the only one in the world to make unbroken profits for 40 long years. While Southwest leased only Boeing 737s, IndiGo’s version of this financial model involved only Airbus A320s. Although other budget airlines have also taken up this model (some only partially), industry watchers say that IndiGo is the only one that has successfully incorporated the pre-launch purchase of aircraft into its business plan. Using only one type of aircraft allows the airline to keep operations simple, elementary and streamlined. Financially, large sale-and-lease-back orders grant the company enviable bargaining power—some experts reckon even discounts upwards of 40 per cent on the listed price for each plane—with aircraft manufacturers when a deal is signed. The model allows an airline to save on the depreciation provision, thus boosting profits and saving taxes, since the aircraft are owned by a lessor.

But the particular model adopted by IndiGo came in for a lot of suspicion and mistrust from rival companies, many of whose bosses suggested that IndiGo’s profits weren’t ‘real’, something that analysts who’ve studied its balance sheets and profit-and-loss accounts have rubbished.

For all the envy going around in the industry, passengers continue to daily endorse IndiGo’s punctuality and time-saving simplicity over and over. In a market where loyalty points are thrown about like confetti, IndiGo has focused on genuine customer satisfaction. While the sale-and-lease-back model may have contributed at least in part for the fine shape its aircraft are in, minute attention to details—such as requesting disembarking passengers to keep seat belts and seats in their original position, and encouraging them to dispose of all garbage before landing—helps crunch a plane’s turnaround time. Besides, IndiGo’s aircraft also use the more advanced and efficient ACARS system that permits enhanced radio contact with airport control towers and helps cut down landing time sharply even while other airlines fly faster to destinations only to keep circling in the air before they get landing clearances.

Simplicity is the leitmotif of Bhatia’s personal life, too, a kind that makes both sense and money. Somewhere in the course of our conversation, the group head of InterGlobe Enterprises excuses himself to make a call. And begins talking to an airport ground staff official for IndiGo. “My mother is travelling abroad today. She needs a wheelchair. Could you take care of that please? What gate should she come to?” No haughty ‘Koi hai’ here. Bhatia, whose sartorial sense is partial to casual shorts and tees when he travels, is known to travel light and stay fiscally frugal. According to a Forbes story, on the 25th anniversary of InterGlobe Enterprises last year, he asked “Why waste money on larger-than-life celebrations?” If he were to put it in simple terms for the uninitiated, how would he describe his business ethos? “Think twice before you spend a single rupee. Ask if it is absolutely necessary or can I do without it?” That, he says, is the thinking that allows IndiGo to be profitable and efficient, even while charging passengers among the industry’s lowest fares. At first, that line of thinking made IndiGo avoid investing in airport lounges. More recently, however, there has been a rethink.

“I must admit that there are days when I look at what we are doing. Despite the impression that the world has about the difficulty of doing business in India, I marvel at what this journey has turned out to be for us. Dispensations have been supportive. This journey was not that difficult partly because we had very little to ask of the Government. We have been running on our own steam. We got the licence to operate when Mr Rajiv Pratap Rudy was the Minister [of Civil Aviation]. And we operationalised the airline when Mr Praful Patel was the Minister,” he says. “When we faced a problem, we tried to face it in our own righteous way. The journey has been remarkably smooth. I find that the impediments in the hotel space are way more than in aviation. From acquiring land to opening a hotel, it is a mind-boggling maze.”

IndiGo, meanwhile, has become weightier. Today, nine years down the line, the airline has become the country’s single largest, flying one of every three domestic passengers in India. It recently secured a $2.6 billion loan from a Chinese bank even as it prepares for a stockmarket listing this year. Once that happens, IndiGo will have to allow public scrutiny of its accounts. In the fiscal year 2012- 13, it reported net profits of $130 million on revenues of $1.6 billion, even as other airlines in the country were slammed by high fuel costs and a weaker rupee. In 2013- 14, IndiGo is estimated to have made profits of $100 million. In short, it has rewritten the script of the aviation industry in India, proving that it is possible to run a no- frills airline profitably without compromising quality, even if the economy is sluggish, if you have the patience and will to take on challenges in a fast-expanding market.

Talking of the edge his airline enjoys, Bhatia says, “I think there is a relentless focus on costs. Relentless focus on what works today is not going to work tomorrow. And that is the religion in the company. We are constantly trying to improve.”

He knows only too well that aviation is a business where every other guy has a view. “What should be done, what should not be, this can work, this cannot, etcetera. Even people who have no understanding certainly have a view. And sometimes you can get influenced by that,” he says, referring to the difficulties of being in this business.

The leadership at IndiGo constantly encourages its employees to come up with new ideas. And it is not that every idea would be embraced. Some, how- ever, are. “I would like to state that in the context of India, I don’t think there is another airline that plans the way we do. We know what should be done 10 years from now. In 2025, how many planes should be added to the fleet, for example. Planning is very important,” says Bhatia.

Aviation is not a complicated business, Bhatia insists. “There are a few cornerstones in this business. We believe in India. We believe in the longer term potential of air transportation. And if I believe in these two, what should be my long-term commitments? Aircraft, maintenance contracts, trained personnel and all that stuff. And the rest comes together. You have to have great people to run the airline.”

The man goes on with a winning smile, “I am fortunate to have a very talented and committed set of people. It is easy to find people with basic competence to do the job. But it is difficult to find people with competence and a passion for excelling—passion to put their best foot forward. That combination is hard to find. But if you find those people, hang on to them with your dear life. Because when the going is good, life is okay, but if the going is difficult, it is those people who have to come to the fore.”

Bhatia knows his strengths and weaknesses very well, as he confides. He has always been a poor manager, he says, but makes up for that gap by delegating work. “I am a great believer in offering autonomy in what my employees do. In all the businesses, I am one step removed. Each of these individual businesses is run by those who more than own those businesses,” says Bhatia, who adds, matter-of-factly, that he has a colleague who once said to him that the scariest part of being with InterGlobe is the independence its employees get. “The ethos of the company is that if we have somebody good, leave him or her to do his or her work. Of course, they may make some mistakes along the way, but that’s part of the learning,” says Bhatia.

He pauses to recollect the details of how he got the name IndiGo. “My initial journey to set up an airline was what is now known as Spicejet. [Industrialist Bhupendra] Kansagra had bought what was called ModiLuft. It was a publicly listed company. He had substantial ownership. In early 2000, he came to me and said that he wants to relaunch this airline and he wanted me to provide services for the airline. I said, ‘While we are happy to do this for you, you need to rehash your business plan’,” Bhatia says.

When they finally came to Bhatia, they already had a plane they had leased. They were going to name the company Royal Airways. But soon, Bhatia realised that the relationship couldn’t be sustained. “So we decided to do our own thing. So SpiceJet got launched. But in that journey, Royal Airways was renamed IndiGo. When it got launched as SpiceJet, I bought this name back from Bhulo (Kansagra) for Rs 25,000,” says Bhatia.

Now, how important is branding for the man whose ad team takes pride in being associated with him? “Frankly, it is not much. We could be running the ugliest airline in the country and do just as good as we do. The uniform could have been dirty brown. People would come and fly with us for what we stand for. Branding can give a feel- good thing, but it can’t bring more people into a plane if other things are not in order,” he springs a surprise.

Bhatia talks about the philosophy of his success. “Your speed should be such that you should be able to kill,” he says, emphasising that Indians have started appreciating the value of time. He also shares his grand ambition: “We want to be the Southwest of India [the world’s biggest airline that ferries 4 billion people].”

Bhatia says what drives him most is his enormous faith in business possibilities in India. “Which is why I will take more flights to Dimapur [IndiGo’s latest destination] and not Los Angeles,” he argues. Of course, that doesn’t mean he will confine himself to opportunities in India. Bhatia, suave and Westernised, has a great fascination for cities and locations that connect one civilisation or continent with another. No wonder then that his favourite destination is Istanbul, where the East and West meet seamlessly.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

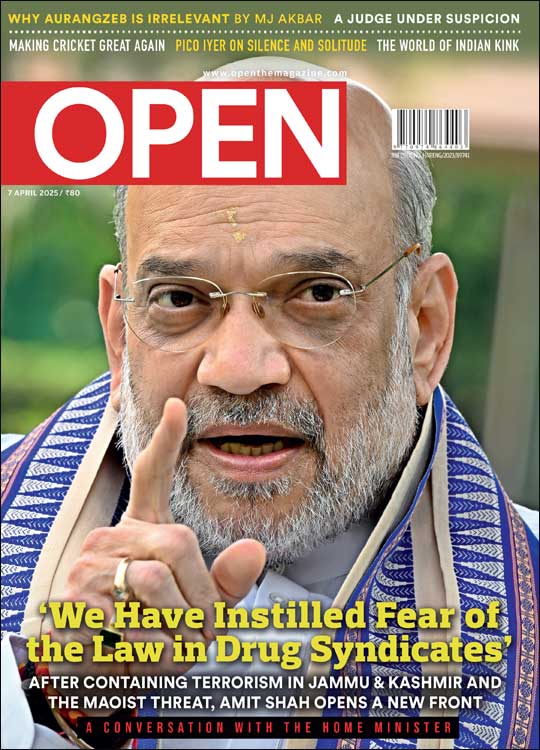

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post

What’s Wrong With Brazil? Sudeep Paul

A Freebie With Limitations Madhavankutty Pillai