The New Freedom Struggle

Ordinary citizens who shaped the RTI Act

Anjali Bhardwaj

Anjali Bhardwaj  Anjali Bhardwaj | 24 May, 2018

Anjali Bhardwaj | 24 May, 2018

/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Freedomstruggle1.jpg)

THE RTI STORY is an authoritative chronicle of the evolution of what has come to be known as the ‘right to information movement’ in India. It traces the history of the grassroots peoples’ struggle, which articulated the demand for an effective right to an information regime, and the subsequent national campaign for a law codifying the right. The book deals with the pre-2005 journey of the right to information movement—upto the passage of the national RTI Act.

Though legislations guaranteeing people the right to access information exists in more than 100 countries across the world, the Indian experience of the enactment of the RTI law has been unique. The RTI Story documents how the legislation in India was demanded, and fundamentally shaped, by the ordinary citizens of the country—living in remote rural areas and settlements of the urban poor—who understood how the right to access information from public authorities would empower them to access basic rights and entitlements like minimum wages, rations and pensions.

With around 60 lakh information requests filed every year, the Indian RTI Act passed in 2005, is the most extensively used transparency legislation globally. The widespread use of the law and its strong ownership by the people of the country, is inextricably linked to its evolution. Therefore, the book is an important read for those interested in understanding the journey of the RTI in India. It traces how people prior to the enactment of the law, identified access to information as key to them holding the government to account for delivery of basic services. Workers employed in drought relief work in rural Rajasthan were denied their rightful wages, as government officials claimed that according to government records they had not completed their assigned work. Ironically, however, officials refused to share records, which were labelled ‘confidential’. The asymmetry of information left the workers at the mercy of the local power centres and bureaucracy. Recognising that access to these records was crucial as the files held the ‘truth’, the articulation for a right to access these records took shape.

The RTI Story documents and acknowledges the contributions and efforts of people across the social and economic spectrum who worked tirelessly for the transparency legislation—workers, peasants, journalists, academics and lawyers. It provides a detailed account of how local villagers in Rajasthan, with the help of the Mazdoor Kissan Shakti Sangathan, engaged in the grassroots fight for transparency through dharnas and Ghotala Rath Yatras (a spoof on the rath yatras taken out by politicians to highlight corruption scandals). The book underscores the critical role of theatre, song and other forms of cultural expression, in connecting the RTI with people and popularising its message.

The book provides a detailed account of the processes, and also the people, groups and campaigns like the National Campaign for Peoples’ Right to Information (NCPRI), that contributed to the drafting of the RTI bill and shaped its arduous journey through the corridors of power. It also highlights the significance of the enactment of RTI laws at the state level by various state governments, prior to 2005—how these laws provided a glimpse to people of the transformative potential of the RTI law and galvanised the campaign for a national legislation.

The RTI Story through anecdotes and narration of stories from the ground, lucidly conveys how the demand for the right to information in India was rooted in the understanding that access to information is fundamental to the right to live. In a democracy, no meaningful accountability is possible without an informed citizenry. The book provides an insight into the Indian RTI journey wherein these powerful ideas were encapsulated in slogans which emerged from the grassroots and continue to reverberate even today—Hum Janenge, Hum Jiyenge! (Right to know, right to live!) and Humara Paisa, Humara Hisaab! (Our money, our accounts!)

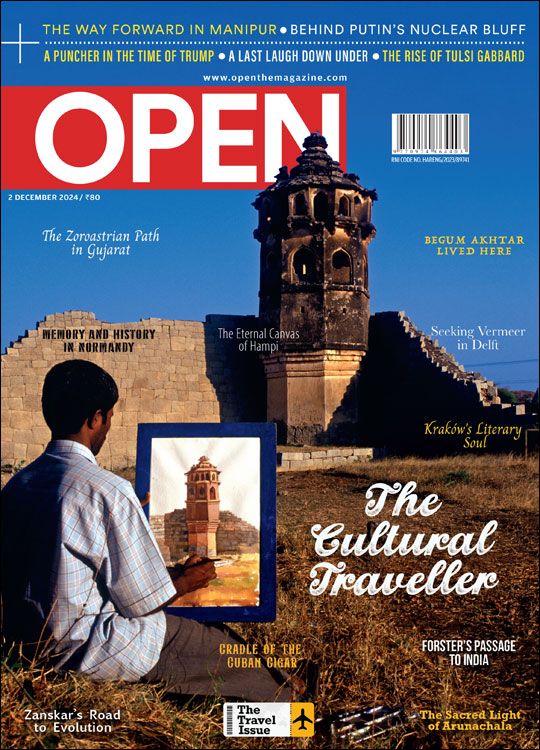

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Cover-Travel.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Syeda-Saiyidain-Hameed1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/SaltandSand1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Memories1.jpg)

More Columns

Old Is Not Always Gold Kaveree Bamzai

For a Last Laugh Down Under Aditya Iyer

The Aurobindo Aura Makarand R Paranjape