She was not an actress; her greatest performance was in playing herself: Suchitra Sen, the luminous superstar.

Mrs Sen touched my life, too. Yes, the Mrs Sen whose body turned to ashes on a sandal wood pyre on 17 January, and no, I did not know her, never saw her in flesh, never even saw her movies when she was in her prime. It was Vanishing Prairies or Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea for children then, not the romcoms that were Sen’s forte. But growing up in Calcutta in the 1950s and 1960s, there was no escaping the larger-than-life persona of Suchitra Sen, on screen and off. It was also the time of Satyajit Ray, but the middle-class Bengali mind never fluttered at his masterpieces the way it did with the overly-romantic melodramas starring Suchitra Sen, never let him shape their lives the way she did.

My parents, uprooted by Partition, were painstakingly building a new life for themselves more in keeping with the changing times. And they got their cues from the Suchitra Sen-Uttam Kumar starrers that were their staple cultural diet. Soon, a decision had to be taken about my schooling. My father was too busy; my mother, who had some education but no formal degree, found out that Sakhawat Memorial School for Girls was one of the more respected schools in the city and not too far from our home. There I was admitted, the uniform was made, the books were bought when, a few days before classes began, my father realised what was about to happen.

“No,” he burst out, “she will have no future unless she goes to an English medium school.” So I did; and it was all Mrs Sen’s doing.

Not that English diction was her strongest suit. Rather, the one English word in the challenge that Sen’s Rina Brown throws at Kumar’s Krishnendu in Saptapadi with whom she was yet to fall in love but who was to play Othello to her Desdemona in their college play—“Abhineyer samay amake touch karte parbe na (You can’t touch me when we’re acting)—offers us a clue to why the director thought it wiser to let Sen give only lip service to Jennifer Kapoor’s rendition of, ‘And yet I fear you; for you are fatal then / When your eyes roll so: why I should fear I know not / Since guiltiness I know not; but yet I feel I fear’ (while Utpal Dutt reeled off the lines for Kumar’s Othello).

A mere detail. What mattered was what Suchitra Sen symbolised to the burgeoning Bengali middle-class: the acme of modernity, the new woman for a new age that was seeing a social churning with the Hindu law being reformed, caste and zamindari being abolished, universal adult franchise being instituted. Several of her 40-odd films made in the 50s and 60s, especially the ones that became superhits, from Agni Pariksha in 1954 to Saat Paake Badha in 1963, saw her in the role of a confident, educated, self-assured woman, spouting English with apparent ease, an adored daughter of an affluent father who nevertheless had a career of her own, an independent woman who chose to put her career on hold to give primacy to the needs of the man she loved, a strong woman who was not defined by the men in her life but who, nevertheless, had due regard for the norms of marriage and familial ties, a stylish woman who set trends in fashion but was never risqué. Every proud parent’s dream daughter, indeed.

It helped that Mrs Sen commanded respect off-screen as well. Born into a professional middle-class family not from Calcutta, she was married while still at school into one of the city’s more privileged families. It was the year India became independent. Her father-in-law was both a wealthy and respected lawyer. The snobbish Calcutta society was ready to defer to the daughter-in-law of Adinath Sen more readily than it was to, say, Kanan Devi, the star with humble origins who had dominated the Bengali silver screen just before Sen.

Especially as she, already the mother of a one-year old child, had entered films not only with the approval of her well-regarded father-in-law but at the behest and active participation of her marine engineer husband, Dibanath Sen. True, he was thought to be a bit of a wastrel and a playboy, but no one could fault Mrs Sen for acceding to her husband’s wishes by joining a world that society still did not quite approve of. It was Dibanath who spoke to producers and studio heads for an opening for his wife, accompanied her to meetings with directors and screen tests. He has even been seen, in the early days, lolling against his Morris Minor outside a studio while his wife was busy inside. And, when things turned sour, the marriage faltered, Suchitra neither divorced nor publicly disowned her wayward husband. He died in America in 1969, away from his family.

The idea of films may have come naturally to Dibanath. Apart from being exposed to Hollywood films from a early age, his father’s late lamented first wife had been the sister of Bimal Roy who was already on his way to becoming a legend in Bombay. Despite the death of his sister, Bimal Roy had never lost touch with his sister’s widower and his family. No wonder that Mrs Sen’s foray into Bombay happened as early as 1955, barely two years after she’d entered show biz, as Paro in Bimal Roy’s Devdas.

Suchitra Sen, however, did not remain content with this thin veneer of social endorsement for protection in what was most emphatically a man’s—and rough and ready men’s—world. Instead, she built on it and converted herself, through sheer will power and personality, into a figure that commanded both respect and awe within the industry and out. In a society that cannot express admiration without being familiar, she was, to one and all, never Rama, her given name, nor Suchitra, her screen name, nor even the ubiquitous ‘Didi’ but the distant and formal Mrs Sen, or Madam; someone you did not dare be intimate with. They said she was moody and unpredictable; they said she was difficult; a tough nut; they said she was standoffish and unapproachable.

Small price to pay, surely, for demanding and getting, as she did, a make-up room all to herself, the first time a female artiste was given one in Tollygunge, a make-up man solely for her, a separate title card in the credits for herself, her name ahead of Uttam Kumar in the Suchitra-Uttam starrers, encouraging a more professional atmosphere at studios by banning outsiders, including journalists, during her shoots—raising in the process the profile of all women in the industry.

The kind of woman she played, and the kind of woman she was may have been the kind of woman our parents wanted us to be but there may still have been a Suchitra Sen mystique to unravel even if she had continued to act in films like Bhagavan Srikrishna Chaitanya, the 1954 movie that first brought her to public notice. That was when people first became mesmerised by her lovely, ethereal beauty, her flawless looks that held her audience captive in her heyday and continue to cast a spell even today, as seen by the popularity of the reruns of her films on television.

Of course, this is beauty as it was understood in those innocent times when it was a face that drove droves of fans to the theatres, not a body. Mrs Sen never set out to be nor was she ever promoted as a sex symbol of any kind. Gazing at her, enraptured, the Bengali mind would quiver, but gently. She would create no ruinous storm.

It was all in her face, a face that the camera simply adored. Her liquid eyes, finely-etched brows, her striking forehead, her slightly arrogant nose, her enchanting smile, the black spot on her cheek (not being nature’s gift it appeared at times on her left cheek, at times on her right), her natural loveliness—nothing is dimmed or rendered unappealing whatever the angle of the camera. This is what gives her her much-vaunted screen presence, her hypnotic qualities, her unparalleled success.

No surprise that all her films are dotted with close-up after close-up after close-up—of her face. Think of Suchitra Sen and you think of the flick of her head, her raised brow, her saddened eyes, her trembling lips, her sculpted throat stretched taut—parts that add up to her whole captivating face. She had a relationship with light that was quite unbelievable; wherever you directed it on her face, it created luminosity, a play of light and shadow that wrought magic in those black-and-white days.

It stands to reason that some of her greatest hits emerged from the hands of cameramen-turned-directors like Ajay Kar (Harano Soor; Saptapadi; Saat Paake Badha) and Asit Sen (Deep Jele Jai; Uttar Falguni and its Hindi remake Mamta, helmed by Sen as well). And Mrs Sen knew it, too. She reportedly backed out of working with Ritwik Ghatak in Ranger Golam because the cameraman was not someone she was familiar with. She was not going to tempt fate just to work with a great director even if it was someone who was fond of her and had written the script of her second Hindi film, Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Musafir (1957).

In the Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema by Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen, the entry on Suchitra Sen notes: ‘Her assertiveness on screen was coupled with a personal anxiety over the way she was photographed while her rigid gestures and mask-like make-up at times contradicted her strong screen persona, dividing the star from the stereotype, e.g. Hospital.’

People have found simpler ways of saying Suchitra Sen was not as great an actress as she was a star (if that is what it means, I could be wrong). Anyway, it takes nothing away from Mrs Sen’s greatness to say that it was by learning to play herself, and by continuing to do so, more or less for the whole of her career, that she became a screen icon and goddess.

Being herself hadn’t been easy. She had had to work, and work really hard, at it. Initially even on her Bengali, struggling to remove her pronounced East Bengali twang picked up during her childhood in what is now Bangladesh and replace it with the clipped Calcutta accent that sophisticates were supposed to speak. The sartorial elegance of upper-class city girls (it was said she changed clothes 32 times in Pathe Holo Deri, one of her earliest colour films, to the extent of wearing one sari when she got into a taxi and another when she alighted from it) was also something she had to teach herself, as also the finer points of make-up and hair-styles.

So, wisely, knowingly, deliberately, Sen chose to stick primarily to what she could not fail in: romantic mush, avoiding other types of roles or demanding directors. Her capital, her bewitching face, is essential for a romantic heroine; it is to her credit that she made it a sufficient condition as well. That is the role she played over and over again, and not just with Uttam Kumar.

Even the Best Actress award that she received at the 1965 Moscow Film Festival—the first international jury award by any Indian actor—was for a romantic drama, albeit one that ended in separation and loss: Saat Paake Baadha.

She wouldn’t leave her comfort zone come what may, as a young Gulzar learnt to his cost. She had demanded changes in the first script that he had brought her because there were things in it that did not quite suit her. “I did not write the script to suit you,” an impetuous Gulzar is said to have retorted, “I wrote it to suit the character. You would have to change accordingly.” It wasn’t until he had a script that was a natural fit for her—the driven but heart-of-gold Aarti of Aandhi —that they got to work together.

Around 1961, there was talk of her working with our greatest director, Satyajit Ray. He had approached her for the title role of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Debi Chaudhurani; she had agreed but then backed out, refusing to give Ray the exclusivity during shooting that he asked of her. Ray never did make that film, but Mrs Sen did, with another director, in 1974. It was not one of her memorable efforts.

So it was almost inevitable that Mrs Sen would have to walk away from the film world after her latest release bombed in 1978. She was then 47, too old to be a romantic heroine, and she didn’t know, or wanted to know, anything else. She never made another film, never involved herself in anything related to films, never engaged in public life at all. She even refused the Dada Saheb Phalke award in 2005 because it would mean personally having to go up to receive the award from the President. Giving, in the process, a fresh lease of life to the myth and magic of Suchitra Sen.

But actually, in her canny, hard-fought battle for privacy, Mrs Sen established a model for superstardom that turns everything we know about celebrity on its head. She was so successful at silence that she accomplished a quiet revolution in mythmaking that must have today’s fame-seekers seething. In a celeb-hungry age when any two-bit wannabe starlet gets more than her 15 minutes of fame, the real money is in mystique — the gold standard of any cultural economy. And nobody sits on a bigger stockpile of mystique than a recluse.

In the end, I don’t understand why anyone who could choose to live as some sort of recluse wouldn’t do so. It seems such a perfect, elegant expression of control: to occlude the flow of trivia in one’s life; to accrue and manage fame on one’s own terms; to engage with people you trust and appreciate. Mrs Sen did just that—and managed to do so even beyond her passing. She was, and always will be, incomparable.

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/suchu1.jpg)

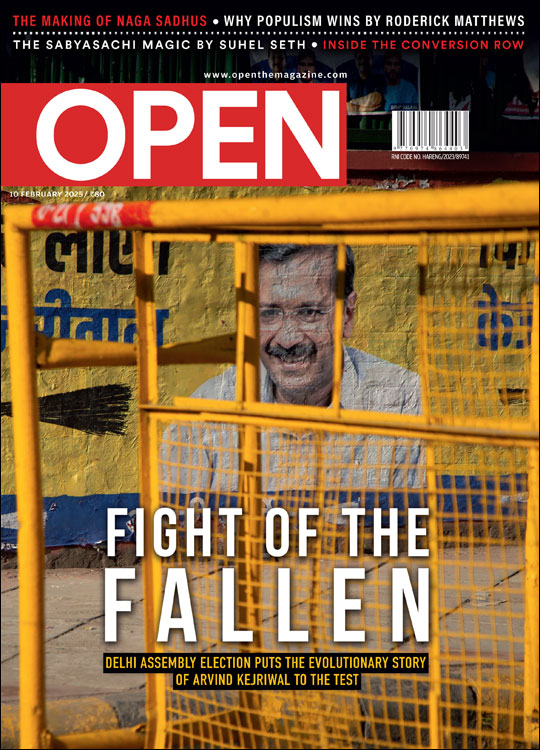

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover-Kejriwal.jpg)

More Columns

Revealed! Actress Debina Bonnerjee’s Secret for Happy, Healthy Joints! Three Sixty Plus

Has the Islamist State’s elusive financier died in a US strike? Rahul Pandita

AMU: Little Biographies Shaan Kashyap