Bored of Censors

In film censorship, it's the man or woman on top that matters

Unless you're a certified alcoholic or someone dealing with anger management issues, booze generally brings out a cooler, better version of yourself. This was no different for Vinayak Azad, who I was meeting for the first time outside his uptight work-space, at a party in Blue Frog in Mumbai. As the evening progressed, Vinayak and his friend, both Customs officers from the Indian Revenue Service, regaled me with stories of narcotics raids in Goa. They both wore the same tattoo—fish skeletons— on their arm and generally seemed like regular fun people to be with.

The reason I knew Vinayak, a major film buff with a keen interest in the arts and other humanist things in life, is that he was the regional officer of India's film Censor Board. During his term, the English press had rightly noted a decline in the Censor Board's draconian ways. Vishal Bhardwaj's Omkara was a good example, where the characters could talk like dacoits without the dialogue getting beeped to protect adults from foul language of their own street. Vinayak had asked me to be on the advisory panel of the Board. I suspected he knew what he was getting into.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

The cultural commissars on the Censor Board, much like juries in the US, are supposed to be regular citizens called upon to certify films as and when the State requires them to. My strategy while participating in post-screening discussions was to simply jump in first and argue for a 'U' (Universal) certificate with no cuts, regardless of the film's content. Having started the conversation thus, one hoped the group (of three or four, usually) would at least arrive at a 'U/A' or an 'A (Adult), with no cuts'.

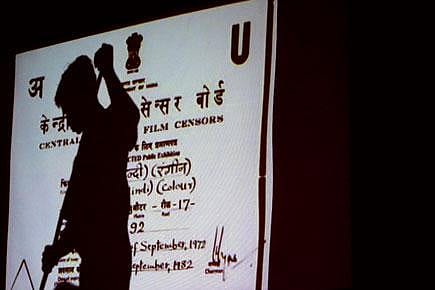

In any case the job of the Censor Board, as per its official title—Central Board of Film Certification—is merely to classify films rather than censor them. The Government's regional officer, while supposedly an observer at post-screening discussions, inevitably influences the final call. Although cautious to a fault, as most civil servants are, Vinayak would inevitably be the voice of reason. The other group members I came across, besides some sensible ones (like Nandini Sardesai), were generally bureaucrats' wives or 'social workers' (a euphemism for political activists or party hacks).

After Vinayak left, the position of the Censor Board CEO that had been lying defunct for years was reinstated. His successor Pankaja Thakur, who became the CEO, was also an officer from the Customs. The Censor Board CEO and regional officers are bureaucrats who report to the chairperson, who is usually a person from film, letter or arts. Actor Sharmila Tagore used to be Vinayak's boss. Danseuse Leela Samson was Pankaja's.

While interviewing for the position, Pankaja told me she had even made a short film to prove her interest in cinema. A major problem she faced in her job was from rag-tag groups and NGOs that could get offended by any content and they had to be heard. If you leave censorship to the public at large, there will be little left of art itself. Television currently follows that model. Censorship on it borders on the ridiculous.

Pankaja's bosses in the Government, she said, hardly interfered with her work, but for once when a joint secretary was upset because the grotesquely funny adult comedy Delhi Belly had been cleared without cuts. The State was more concerned with content being generated on the internet. Be that as it may, according to rumours, Pankaja was apparently thrown out by the Congress Government, right before elections, for passing a film, Punjab 1984, on Delhi's anti-Sikh riots.

Pankaja's replacement, one Rakesh Kumar from the Indian Railways, right after assuming charge, announced in Mumbai Mirror (Bollywood's best-read paper) that he was going to clean up all the mess being created in the name of film entertainment that he could no longer enjoy with his family and kids. The Censor Board went back to roughly how it used to be in the 80s or 90s.

In line with India's knack for hypocrisy, the morally upright Kumar sahib was caught with, well, not lots of porn stashed in his computer (although someone should have checked), but with bundles of notes amassed while doing the job of certifying films. He was booked on bribery charges. His legacy continued.

His office secretary, certifying films thereafter, asked the makers of Finding Fanny to delete the word 'virgin' from the film. Vishal Bhardwaj's Haider had to go through 41 cuts. The Censor Board's rules, based on a 1952 Cinematograph Act, hadn't changed. Only the people had. Going by the same guidelines and regulations, Vinayak once told me, you can ban Tom & Jerry if you like. It only depends on the man or woman on top.