EDITOR’S NOTE

Change is more than an abstraction animated. It is a collection of synonyms for the next point in the grand ellipse of hope

The word is as old as the human urge for movement. It is the repudiation of stillness, the state of being denied the possibilities of tomorrow, of dreams. It is man's refusal to mortgage his future to destiny—or fate. 'Change' is the oldest assertion of the living.

In politics, it is the oldest cliché, a nauseating one when it is uttered by the usual suspects on the stump. It is a salesman's pitch in the marketplace of slogans. Still, like any other cliché, its overuse is a tribute to its original resonance.

Change was the idea that motored history—for better or worse. From the primordial man's inventiveness to the revolutionary's bloodlust, from the scientist's theory to a preacher's gospel, from the reformist's grand gesture to the entertainer's newest show, change is the shared motivation.

So whether it is Mao's Cultural Revolution or Stalin's Great Terror, Hitler's Final Solution or Pol Pot's ethnic genocide, Lincoln's abolition of slavery or Gandhi's Satyagraha, Mandela's struggle against apartheid or Havel's Velvet Revolution, Karol Wojtyla's Gdan´sk appearance or Jayaprakash Narayan's Total Revolution, change was the passion as well as the destination.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The last century ended with a big bang of freedom, when the dead certainties of ideologies were swept aside by the eruption of 'change'. The liberation of Eastern Europe was the other big clash of ideas—ideas for change—that the West won after the Second World War. The new century began with a breakfast show of horror: 9/11 too was about change—as envisioned by the troglodyte of Islam. The Afghanistan war that followed, now coming to an end, has brought change: the Taliban country is dead, though the Taliban themselves are still alive to kill children in the name of God and change. The Iraq war has achieved de-Saddamisation, a great thing in the history of change, certainly, but it has not resulted in a full flow of freedom. We are in the ISIS age—another version, or perversion, of change.

Politically, the new century of change began with Obama—for an America mesmerised by a man who spoke like a prophet and wrote like a novelist, it was O!bama. In the America of his 2008 campaign, to quote the poet, 'bliss was it in that dawn to be alive' for the Blacks and the young, and for everyone who believed in the man who said, "You are the change." I was there on Election Day, covering the Obama Revolution, and the America listening to his victory speech was a nation that redeemed the badly abused word 'change'. Paradoxically, President Obama today is that peculiar leader of the Free World who did little to bring change to countries when they needed it—Iran or Egypt or Syria. And at home, maybe with the exception of healthcare, he is a master of tentativeness and triangulations, not really characteristics of one who is the change.

The other big performance of change in politics was—and still is—the Narendra Modi revolution of India 2014. Even as he painted an India of tomorrow not in pastel but in the bright colours (notably with the exclusion of saffron) of hope and liberation, he was repudiating the national burden of inheritance. After all, India is one democracy where every variation of salvation, no matter whether it is abandoned by history elsewhere in the world, is at play; and it is one place where fossils and fantasists, caste mongers and class warriors, social engineers and community guardians—their idea of India smaller than their constituency— exist in workable disharmony.

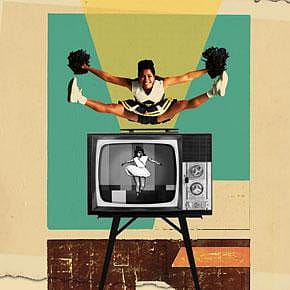

It was that India which Modi, the usurper who came from below, the outsider who dared, wanted to change, and in this project, he was his own cheerleader (the party joined later) and the semaphore he held was his own life story. His campaign too, like Obama's before him, redeemed the sloganeer's cliché. Modi in power is a manifestation of an India liberated, a nation dreaming, of a people refusing to be trapped in the matrix of mediocrity. It is, most importantly, a responsibility: never go the President Obama way. Prime Minister Modi has to be as interesting—and effective—as Candidate Modi. Change is the permanence of renewal.

That said, you will not find a profile of Modi in the following pages, which, taken together, present a portrait of change. Modi won the election largely on his biography, which is a rare one in the history of power. And it is still evolving. The coming months will tell us whether it is keeping pace with the expectations of an India that chose him.

Our writers, after much editorial debate that blackballed some and included others at the last minute, are offering you not only captivating life stories of change but first-rate pieces of narrative journalism, which is all about storytelling. And each story is one of overcoming, of the uses of adversity, of defying barriers, and on their wreckage, building dreams. Change is more than an abstraction animated. It is a collection of synonyms for the next point in the grand ellipse of hope. It is a selection of stories that stand out in the everydayness of our life, and in their social sweep and individual style, they tell the larger story of an India that abhors stillness.

And they appear in a magazine that strives to change the arguments of change. And journalism, at its best, is storytelling—stories that are different, visible in our midst but not seen by everyone. And these stories appear in a magazine whose every page is an intellectual curiosity, and an investigation of the mind and methods of our time. The stories, told by some fine writers in journalism, are an Open invitation to join the many enchantments of being the kinetic agents of change.

Wishing you a happy New Year.

Also Read

The Prime Mover