A Coat of Many Colours

One of the sadnesses of the post-1947 era is that to a great extent an awareness of the importance of the Hindu contribution to artistry in Sindh has been misplaced. This is not to suggest that this was orchestrated; simply that the emptying out from Sindh of the Hindus, that could have advocated and articulated the message of the relevance of their community, was almost total. Both the Lohanas and the Amils left almost entirely (Hindus, 29.25% of Sindh in 1941, were down to 4% in 2017). What remained, except for isolated pockets, were the Rabaris and Kohlis, largely confined to Tharparkar who eked out a bare existence and had neither the time nor the skills to represent their community.

A remarkable statistic quoted by Sarah Ansari of the University of London demands our attention in this examination of the role of the Hindu in Sindh. The percentage of Hindus in Karachi in 1941 was 51%; in 1951 it was down to 2%. Why was there such a mass flight of Hindus from the province in 1948? As documented elsewhere, in 1947, Hindus in Sindh were both significant in numbers and dominant in trade and commerce. One of the reasons behind the precipitate departure of the bulk of the Hindu population may have been a fear of religious disharmony. But religious disharmony was endemic across pre-partition India and not necessarily, a recent phenomenon. For instance, the Chachnama, the oldest extant historical source on Sindh, states that the Brahmin ruler, Chach, imposed harsh restrictions on the Jats and the Lohanas (both Hindu denominations) forbidding them to use saddles or wear turbans and compelling them to wear only coarse garments and to travel barefoot.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Similarly, following the Arab conquest (circa 711 CE), the Arabs continued the repressive practices of the previous Brahmin rulers, and the former Hindu rulers (the Samma dynasty) were reduced to becoming artisans, primarily dyers and the women folk obliged to wear uncut cloth. These restrictions did not deter the Hindu population from continuing to live and prosper in Sindh. The demographics of the province changed following the Arab conquest. A process of migration and proselytising meant Sindh ended up with a Muslim majority but with a substantial Hindu minority. In some respects, this could be regarded as a tectonic shift but it did not have a discernible effect on the newly created minority.

In colonial times, sectarian violence was much more prevalent in say, United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh in India) than in Sindh. There was no equivalent in Karachi of the ‘Great Calcutta Killings’ in 1946. But in spite of the riots in Calcutta (and comparable ones in Noakhali, now in Bangladesh, also in 1946) there was no wholesale evacuation of an entire community. In fact the Muslim population of West Bengal in 1951 was 19.85 % and the Hindu population of East Pakistan, 22%. (The Muslim population of West Bengal had increased to 27.01% by 2011; the Hindu population of Bangladesh however, has declined over the years and was 8.6 % in 2011. But unlike Sindh, in both cases, there was no flight to safety).

There were riots in Karachi in 1948 but not anywhere near the magnitude seen in the Punjab or elsewhere in North India. So to what can we ascribe this wholesale departure?

The best guess is a sudden loss of confidence in the state and a failure of statecraft on the part of the new government. There is anecdotal evidence for this. The Mohatta Palace in 1947 was the summer resort of the Mohatta family who would escape the heat of Rajasthan for the balmy, seaside comforts of Karachi. In 1947, it was requisitioned by the Pakistani state to house the first Foreign Ministry of the country. Shivratan Mohatta, who was resident in the building at the time and a personal friend of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, remonstrated with Jinnah that he was being thrown out of hearth and home. Jinnah, was, if anything, secular, with many Hindu friends, but he had little flexibility because there was literally nowhere else in Karachi that the newly formed Foreign Office could be billeted. Rumour has it that Mohatta, incensed at the apparent absence of natural justice in the country, said to Jinnah, if this is your Pakistan, you can keep it, and left the next day for Bombay. The story may be apocryphal but it strikes a chord.

That Mohatta will have left Karachi with a huge sense of loss is supported by the views expressed by LK Advani, one of the founding fathers of the Hindu nationalist political party, the BJP, who wrote as recently as 2008 that ‘Karachi was his favourite city.’

The Hindu faith practiced by the Sindhi was not the muscular version common in neighbouring Gujarat. The Sindhi version was somewhat syncretic incorporating Muslim Sufi thought with Sikh strands on a Hindu platform. In fact, till politics intervened, there were regular pilgrimages by Sindhi Hindus to meet their Sufi ‘masters’ in Pakistan. What this suggests is that it should have been relatively easy for the Sindhi Hindu to find his place in the new dispensation. But this did not happen. Karachi is Pakistan’s most, possibly only, cosmopolitan city. How different would it have been had it retained some elements of its Hindu character post 1948.

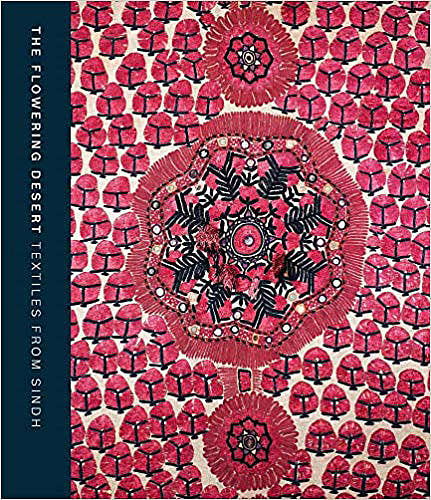

(This is an excerpt from The Flowering Desert: Textiles from Sindh; Paul Holberton Publishing; £35.00; 160 pages)