‘Writing is a bad habit of mine. I have never stopped,’ says Anita Desai

When Anita Desai signs into our Zoom call, with the assistance of her daughter and fellow author Kiran Desai, she is perturbed. Kiran explains that the previous interview, with a national newspaper, ended on a stressful note. The journalist had forgotten to record the interview, and realised this only at the end of the half-hour conversation. While the oversight of not recording is the nightmare of every journalist, the experience has clearly ruffled mother and daughter as well. I press the record button, and the duo sigh with relief. Kiran leaves her 87-year-old mother at work, and I am immediately taken to the world of In Custody (Anita Desai’s 1984 novel) where a Hindi professor in Mirpore town embarks upon interviewing a renowned Urdu poet Nur Shahjenabadi, on the request of a friend who runs a magazine. The project besieges the hapless professor, with woes and burdens. The nadir being that all the tapes he has recorded Nur on are worthless. At the end of spending hours with the poet (and putting up with his demands and tantrums) the journalist has nothing to show for it. All because of technology, which played truant. It seems befitting that when one interviews Desai, fact and fiction embrace so perfectly.

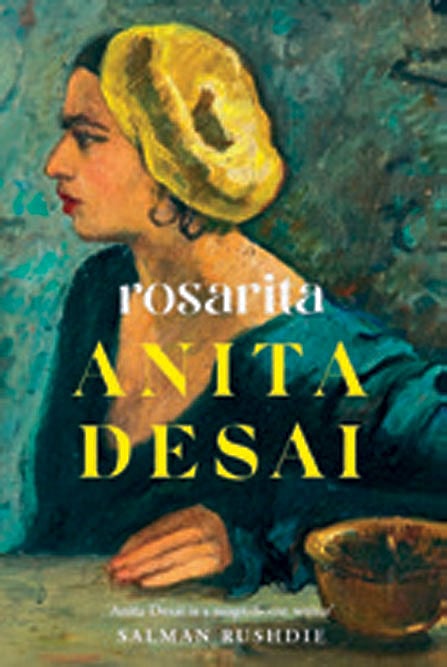

Desai enjoys drawing connections between past and present, life and art. In her latest book Rosarita (Picador; 112 pages; ₹499) Desai returns to the public eye after nearly a dozen years, and once again juggles past and present. Rosarita it

must be said at the start, is not a novel. Desai’s previous publication was a triptych of novellas, The Artist of Disappearance (2011). And the hullabaloo around Rosarita can only be understood if it is seen as the celebration of the return of a legend. It is a novella both in its length and scope. It seeds a saga, but seems thwarted at the branch. It is not a bonsai where the whole is seen in the pruned. Instead, it feels like Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Until August (his posthumous 2024 work) which sowed a compelling idea that never truly bore fruit, and didn’t achieve its potential. Desai clearly is still a master of the fine sentence and the acute sentiment, but Rosarita does not match up to the prowess of her previous novels like In Custody or Fire on the Mountain (1977).

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

ROSARITA OPENS WITH a promising premise, Bonita a young Indian student, is sitting on a park bench in a city in Mexico. Stranger arrives and tells her that she looks exactly like her mother Rosarita, a painter from India, who visited Mexico years ago. Bonita protests that her mother had never visited Mexico, and was certainly never an artist. Through the course of the novel, told in the second person, the daughter will zigzag with her mother’s past, all the while questioning Trickster’s intentions and veracity. But Stranger (the fact that she is called ‘Trickster’) is never fleshed out enough. Rosarita has an element of otherworldliness and provides no straight answers, and this is the hook that engages, even while one searches for the original brio of its author.

In many ways, Desai is the Grande Dame of Indian writing, having been shortlisted for the Booker Prize three times in 1980, 1984 and in 1999 for Clear Light of Day, In Custody and Fasting, Feasting. (While Desai never won it, her daughter Kiran received The Booker Prize in 2006 for The Inheritance of Loss.) Desai was born in 1937 in Mussoorie, to a German mother, and a Bengali businessman. Her first language was German and while she writes only in English, she found her way back to her mother’s language in Baumgartner’s Bombay (1988), which told the story of a German refugee in India. She now lives in Cold Spring, a picturesque town, an hour out of New York.

Wearing her grey hair in a long ponytail, Desai speaks in a hush. The pace of her words, her measured pauses, make one recall one’s ancestors. Hers is a voice that ushers past into present. Her novels have always explored the insider-outsider, they’ve mapped vanishing worlds, and chronicled homes and exile. Her concerns in fiction perhaps have autobiographical roots. Her German mother and East Bengali father lived in Delhi, which was home to neither. Her mother, an avid storyteller, would recreate her past in vivid detail. Her father, who was more reserved, provided fewer snippets. But the scarcity of information made it more precious. He told Desai and her three siblings about “travelling down canals on riverboats, the green of the paddy fields and the fish everywhere.” Desai recounts, “We had to cling to these little details and create worlds for them, and I suppose that’s what also taught me how to be a writer. You have a few essentials. And then you have to use them and build whole worlds out of them. But we were aware we were exiles, and were outsiders, and that affected me too, because a writer is an outsider too, you stand outside the picture that you are drawing and watch your characters on that stage. But you don’t belong to it. You can’t belong to it and write about it.”

Desai has been writing since she was seven years old and writing is still part of her daily schedule. If she is not working on a novel, she scribbles notes. She says, “A day when I don’t write always seems to me like a lost day.” After The Artist of Disappearance, she hadn’t planned on writing another book realising that it required an energy and stamina that she no longer possessed. She adds, “But writing is a bad habit of mine. It’s like smoking cigarettes. I have never stopped. I can’t stop scribbling.”

With The Artist of Disappearance she also realised that the novella suited her at this “stage of life best.” Adding, “I could have expanded Rosarita in my younger years. I could have written a whole section on Partition in India and the revolution in Mexico. But I couldn’t do it now.” Which confirms my own suspicions that Rosarita could have been a more sumptuous novel if age hadn’t stymied it.

Poetry has long informed Desai’s writing. She used to often read the works of Rainer Maria Rilke, CP Cavafy, Osip Mandelstam, and Joseph Brodsky before starting on her own writing. The precision and sparseness of poetry attract her. She says, “I’ve always used poetry as a model rather than prose works. Because I’ve always wanted to write my prose as a poet writes poetry, by just concentrating upon the essentials using the fewest number of words and images and metaphors in order to convey the largest amount, and that is still my ideal.”

Desai has also long admired the work of Virginia Woolf and has read her, over decades, for pleasure and practice, as she wished to replicate the cadences. Desai recounts winning a cheque from the literature department at Miranda House, Delhi University. She promptly took her prize money to a bookshop and bought the entire Hogarth edition of Virginia Woolf’s work. She recently reread To the Lighthouse and found echoes with her own work. Here too Woolf was writing “about a mother who no longer existed. And trying to recreate her presence. The essence of her being, of which she remembered very little.” In a moment where fiction and fiction overlap, Desai realised that in Rosarita she was also recreating the mother who no longer existed.

Rosarita is very much a story centred around women. As Desai says, “It turned out to be a book about three women and their interactions. One of them, a ghost. Two of them are still alive, but all circling the ghost, trying to entice her back into their midst.” Over the decades, Desai has moved between the male and female worlds in her fiction. Prior to In Custody, she had specialised in creating scenarios filled with women, whether it was Fire in the Mountain where a reclusive grandmother and a loner great-granddaughter are forced to cohabit in the hills, or Clear Light of Day (1980) a deeply personal family drama that follows Tara, a diplomat’s wife revisiting her childhood home in Delhi. She embarked upon In Custody to get away from the realm of women, as she was “tired of constantly repeating those stories of home and family and restriction and limitation.” With In Custody, she deliberately chose the setup of Urdu poetry, a derelict poet, a struggling professor and a scheming publisher to infiltrate a man’s world. She adds, “There were hardly any females in the book. There were a few, but they were in the background just the way Indian women mostly were in those days. I could hear them banging at the doors and screaming in the background out of frustration and rage, wanting to break through and not being allowed to.” With time and over successive books, she grew confident in creating male characters and with Rosarita decided to reinhabit an all-female world.

DESAI’S WORK HAS often examined the fraught and complex relationship between family members, and how little we might actually know about them. In Rosarita the daughter must grapple with her knowledge of her mother and with Stranger’s stories. She must contend with how much she knows her mother and how much she wishes to know her. Desai elaborates, “It is simply the way we look into our parent’s and our ancestor’s past. We know certain things about them. The things that they chose to tell us, but there’s so much they did not tell us, and we never ask. There’s always an act of imagination required regarding parents and ancestors.”

In Rosarita the second person voice collapses the distance between the reader and daughter. Sample this opening sentence from a chapter, “It is time to search out the Stranger. How and why did you rebuff her when she offered friendship? How could you have turned your back on her, an old woman, disbelieving her? You have learnt now that you would like to believe her, yes.” Desai explains, “I found that using the second-person voice was easier. It makes it more direct and instant.” As a reader the direct address takes some getting used to, and often seems like one is being spoken down to.

While her earlier works were mostly set in India, she travelled to Mexico in The Zigzag Way (2004) and Mexico has since seeped into her work. In her 12th book Rosarita, she moves between Mexico and India, perhaps hinting at her affinity for both lands. Desai has often spoken about her fondness for the Spanish country. She first went there to escape the harsh Boston winters where she taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Rosarita was born from fragments of memories that slowly formed a whole. The main piece was arriving in Oaxaca and stepping out of the plane and feeling that she had returned to India. But then also realising that this country was different from the country of her birth. Desai was last in Mexico when Covid broke and hasn’t returned, not for lack of desire, but for reasons of ability. Even now she remembers the walled garden with the pots of flowers and walking down to the corner shop to pick up a loaf of bread or a packet of milk. “And living quite a simple life. Letting impressions just soak in and not going out in search of stories, but finding them all around me.” In Mexico she met many women like Stranger, those who seemed to shelter vast histories within. “I could build a whole book about each of them,” she says, “people who lived extraordinary lives.”

In the Author’s Note at the end Desai writes that the Indian artist Satish Gujral had visited San Miguel de Allende to study mural art in the 1940s. In Rosarita art is not only the purported pursuit of Rosarita it is also the common thread between Mexico and India and how they’ve chronicled their own histories. The Artist of Disappearance and its three stories dealt with ‘the transforming power of art’ and here art becomes a personal entry point into events of history, whether it is the Partition of India in 1947 or the Mexican Revolution of 1910s.

Desai says she is particularly pleased with Rosarita’s India cover which is a self-portrait of Amrita Sher-Gil in profile. She had never seen it before but feels a “thrill” to think that her work is paired with that of the iconic artist. Desai, a keen follower of art, who owns a couple of paintings by Gopal Ghose, one of the founders of the Calcutta Group, speaks eloquently about why art attracts her as a writer of fiction, and vanishing worlds, “The art is a repository of a civilisation in time and of a civilisation and its place in the world. One can’t visit a country like Mexico and not immediately be drawn into its modern art as well as its prehistoric art. That is how you learn about Mexico. Learn about any country, really. You can’t know the present until you also know the past.” By using art as a window to a civilisation, Desai shows, once again, the intrinsic link between art and life.