Vikas Khanna: Feasting on Life

ONLY A CHEF would worry more about the size of the atta mounds required to make naan rather than focus on the actor’s facial expressions. Especially when the actor in question is Shabana Azmi. But that’s exactly what New York-based Indian chef Vikas Khanna, 51, was doing when shooting with the celebrated Azmi, who has never learnt to cook, for a yet-to-be-named film. As if that was not enough, the chef has written his 39th book, based on his new 15-minute documentary, Barefoot Empress (Bloomsbury; 32 pages; ₹299), he shot on a 100-year-old woman in Kerala who braved the scorn and laughter of her village to fulfil her dream. “Unusual, incomplete dreams fascinate me,” says Khanna, “ I find it inspirational that Karthyayani Amma managed to do what she always wanted to, which is sit in a classroom in first grade, something students take for granted. Imagine the life of someone who couldn’t go to school when she was a child, who was trapped in a marriage she didn’t ask for at 16, with a husband she did not choose.”

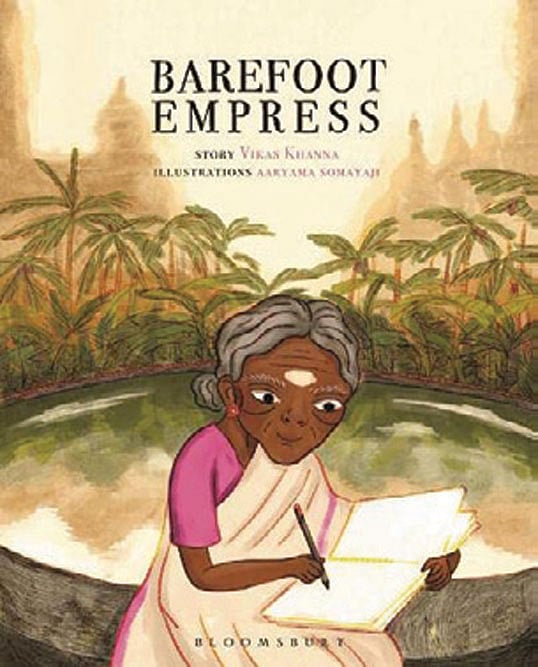

Barefoot Empress is a children’s book with beautiful illustrations by Aaryama Somaji, and Khanna hopes it will inspire everyone to chase their goals. Co-produced with Doug Roland, the moving documentary aims to raise funds for the education of girls in India, hoping to pack in the social impact equivalent to its emotional heft. Roland, an Oscar nominated short filmmaker, hopes Barefoot Empress will inspire change, much as Khanna believes the book will bring greater awareness to Karthyayani Amma’s life— much of which she spent as a widow sweeping streets outside temples in Cheppad in the Alappuzha district, Kerala and bringing up her six children. Presented by Indian-American wellness guru Deepak Chopra, the documentary was shot when she was 96, the year she came first among 40,000 students. Amma started on a good note, says Khanna, but during the pandemic the clock stopped and so did her education. She isn’t in such good health now, says Khanna, but is still a picture of courage.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In a way Karthyayani Amma’s spirit mirrors his own. As she says in the documentary, even though she is bent over with age: “They may not allow me in the temple, but god comes to my home every day, some days in the form of light, some days in the form of blossoms, some days in the form of wind. He is always welcome here.” Khanna too has not met an obstacle he didn’t want to surmount. An Indian chef in the world’s toughest city, he took it upon himself to make Indian food fit the Western notion of fine dining in New York. A graduate of Welcomgroup Graduate School of Hotel Administration, Manipal, Khanna is a James Beard nominee and Junoon—a chic Manhattan restaurant he helmed—won a Michelin star for six successive years. He has two restaurants in Dubai, Kinara and Ellora. He has been featured amongst the 10 most influential chefs in the world by Deutsche Welle and Gazette Review. He is the creator of documentary series Holy Kitchens and Kitchens of Gratitude, and the writer-director of The Last Color, a feature film starring Neena Gupta.

How does he explain his proclivity? A lot of it is a result of people tagging him on social media, he says. He has 2.2 million on Twitter and 2.8 million on Instagram. “I’ve lived a transparent life for the past 20 years,” he says. The relentless drive sometimes is the result of his feeling that he cheated his mother, who continues to live in Amritsar, the city of his birth. “My parents were always there for me. But I left her, I went abroad to make a life on my own, to do things that would make my mother proud, even if she doesn’t understand it. I want her to feel that I left her for a much bigger cause. My Mama is my biggest motivation.”

Which is why he wants to compete with New Yorkers on their terms, with no allowance made for being an outsider. “So if it is an Indian book it has to be the best, and if my restaurant has to win a prize, it has to be the best globally,” he says. He is a proud bearer of Brand India, and if he makes a mistake, especially in the food he serves, he is only too willing to own his mistake. “Our staff is human, it can be a human error. I am not an Instagram chef. I cook in real life.”

He has a new restaurant coming up in New York (where he has lived for the past two decades), and another which has been in construction for 12 years, which he hopes to open next year. “The artwork for it is insane. But I want it to be outstanding.” He’s fighting a culture war, he says, but peacefully, whether it as a person of colour winning a Michelin star for Indian food or producing an internationally appreciated book like the limited edition $25,000 tome Sacred Foods of India, with 500 pages and weighing 15kg. “How many times have I heard the words: ‘Go back to your country.’” But he hasn’t gone, standing his ground, making it despite the odds. “I make sure Americans make an effort to pronounce my name, that they don’t whitewash everything.”

BEYOND FOOD, KHANNA has also made an impressive foray into cinema, directing actors like Neena Gupta and Shabana Azmi. “It’s such a privilege that they allowed me to direct them,” he adds. His film with Gupta, The Last Color, put the spotlight on the widows of Varanasi, and enabled him to raise awareness about the plight of widows at the United Nations. There are 350 million widows worldwide and he spoke about the issue at the US Congress in Washington DC earlier this year. “I was the only man among 11 women. I have always wanted to push the envelope.”

In his second feature film, Azmi plays a failed chef in New York who rediscovers her mojo when she travels to India. “This is not the Bollywoodisation of NRI life,” says Khanna. There are no country houses, private planes and lavish weddings here. “It is full of pain, loss and disinheritance. Making it here is really hard. You have to be alert, crazy, mad to be able to make a shift. It’s the hardest to do in New York but it is also the most satisfying,” he adds.

His movie is about what happens to a woman, who has put her dark life behind her, when her kitchen is taken away from her. He says he makes movies because he pays attention to the universe. The reason to make Barefoot Empress is to ensure there are free schools, which has led to the not-for-profit Leap to Shine to raise funds to educate five million girls. As if that was not enough, in April 2020, during the Covid-19 global pandemic, he started a Feed India initiative which was backed by numerous corporates and sponsors and delivered food and supplies to those in need. As Amma says in Barefoot Empress, “Women are very strong, Sometimes they don’t get a chance to prove themselves.”

Khanna has conquered New York with his easy loquacity and good looks, working his way up the ladder from appearing in small segments on Time Out New York videos to interviews on CNN news shows, from appearing as a guest on cooking shows to hosting his own, from directing documentaries to making movies. He remains emotional about food, whether it is using his grandmother’s chimta (tongs) or his family recipes.

Yet life is not as joyous as it seems. He lost his sister Radhika, fashion designer and author, to multiple organ failure this year. “Mujhe aisa laga ki bhagwan ne mujhe mukka mara (I felt as if god had punched me),” he says. They were close, fellow New Yorkers, and he called her his soulmate. But the universe helped him heal, with “too many people sending me letters, sending me therapy”.

“The reason I am in this position is because I have branded India in a different way,” he says. Always on his terms and always with love. With the heart of a poet and the skin of an elephant, as Salman Rushdie once told him.