The Valley of One

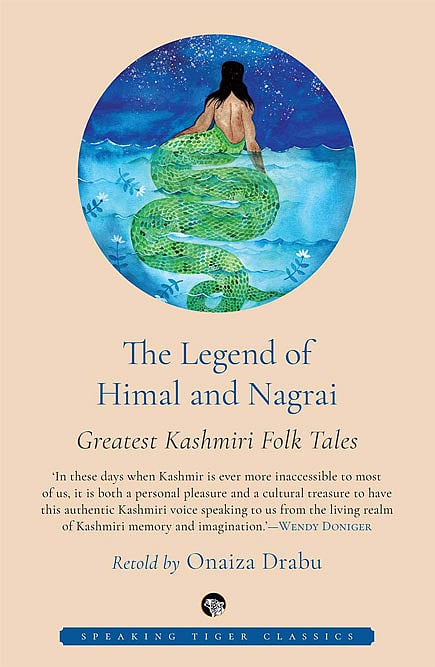

IN THE BOOK, The Legend of Himal and Nagrai: Greatest Kashmiri Folk Tales, there is a story titled, ‘Sona Gada Te Gada Haenz’, in which a golden fish, allegedly ‘the queen of all rivers’, grants several boons like, food, clothes, a mansion, and servants to a poor haenz—fisherman, in Kashmiri—until the day the fisherman’s greedy and foolish wife asks the fish for the entire kingdom of rivers. That day, the golden fish takes all her boons back and the fisherman and his wife again return to their life of poverty. At the end of this simple fable, the re-teller of these folk tales, Onaiza Drabu, mentions that this story could also be found in Alexander Pushkin’s compilation of Russian folktales. In my review copy, I scribble, ‘Stories travel,’ in the margin, and read on in delight as I find at least five stories which I think I have heard in other versions or languages or which I found familiar in some way.

In a story called ‘Noon’—noon being the Kashmiri word for salt—a wise princess compares her love for her father, the king, to salt. The king is angry, but learns his mistake and realises his daughter’s perspective when the same daughter serves him food without putting any salt. In this collection, there is quite some drama between the time the king is angered and when he comes around. I remember hearing this story from my family in Santhali when I was a child. In the version I heard, the story is concluded soon, with the princess immediately serving a meal without salt to her father, thus making him realise the importance of salt and, in turn, of her love for him.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

Similarly, in ‘Hapath Yaraz’—metaphorically meaning the friendship of a stupid friend—there is a bear that ends up killing his best friend, a human, when he tries to kill a bee sitting on the human’s moustache by dropping a rock on the human’s face. I am sure this plot would remind many of us of the story of a monkey who kills his human friend by cutting off his head with a sword when all he tried to do was kill a fly perched on that human’s face.

‘Kokras Kuno Zang’, featuring a greedy but clever attendant and a fowl with only one leg, too reminded me of a story I heard as a child that had a greedy and clever cook and a crane with only one leg.

If the purpose of stories—or literature—is to unite, then this book, I think, serves its purpose well. Despite the several hundred kilometres between Jharkhand and Kashmir, I felt a certain oneness on reading these folk tales that Drabu has collected. Not only the plots of the stories, even the themes and settings of these folk tales from Kashmir reminded me of certain beliefs and superstitions from my home state, Jharkhand. In her insightful introduction to this book, Drabu writes: ‘Kashmiri folklore, perhaps in a cruel twist of irony, tells us that as a race we sometimes enjoy the macabre…that men need to be afraid of beautiful women who may lure them to a brutal end.’ This passage reminded me of the belief in Jharkhand in the saat-bohoni, the seven sisters who are said to inhabit water bodies like ponds and lakes and who lure young men who bathe in those water bodies, ultimately killing those men.

This collection is populated by nagas, half-human-half-serpent beings who are supposed to be the original inhabitants of the Kashmir valley; cannibal giants known as dev; and jinns and rakshasas.

Drabu’s retelling is lucid and some stories, like ‘Zohra Khatoon’ and ‘Shah Lal’, have a rich visual quality. This is a timely volume—the communication blockade in Kashmir warranting that ‘the stories of Kashmir and Kashmiris’ are documented and the world be made aware of those stories.