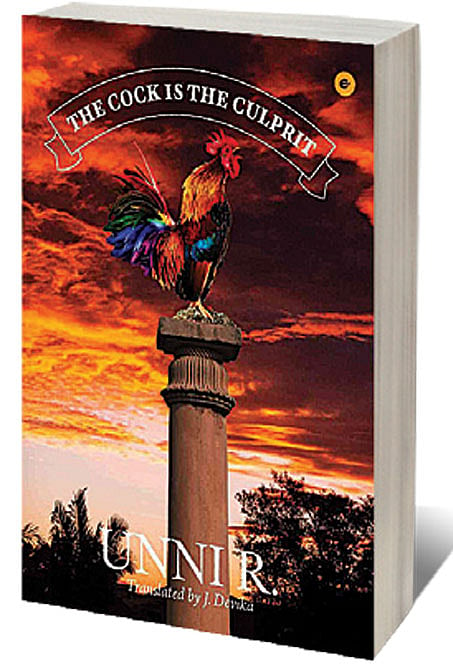

The Rooster’s Revenge

UNNI R’S STORY collection, One Helluva Lover, introduced us to his trademark style, which combines wit and sarcasm (‘the only creature on earth that protests through sarcasm is the human being’) with an unflinching fealty to his milieu of rural Kottayam. His first novel, The Cock Is the Culprit, bears the hallmarks of his writing, even as it explores allegory and gossip as literary devices. The Malayalam original sold 10,000 copies within 100 days of its release.

It’s a riveting tale (‘all tales are lies in the final analysis’), set in small precise chapters, absurdly comic and uncannily contemporary in its references. It’s a modern folk tale that takes in its arc the rise of fascist politics, hypernationalism, religious parochialism and habitual, insidious, unselfconscious patriarchy, lynch mobs, the refugee crisis, police brutality and the untrammelled power of the state, all rendered with a characteristic lightness of touch. In its final summation, this is a story about the essential dumbness of the human race, especially the male of the species.

Unni’s village is a throbbing microcosm of religions and ideologies, cosmopolitan and provincial at the same time. It’s a fishbowl that flows into the ocean. At the heart of this novel is a mischievous elusive rooster that crows hideously at all times of day. Tensions arise in the village because the rooster’s crowing is not whimsical; instead, it seems to deliberately choose the most opportune moments to disrupt proceedings spearheaded by self-important local pillars of society: communists, patriots, the priests of temples, mosques and warring church factions. The invisible rooster pricks each balloon with his beak. It’s not just the big guns the rooster is after: ‘The same horrid cackle was heard when people tried to consult astrologers, when husbands yelled at wives or beat them, when men indulged in post-orgasmic neglect of their wives or lovers, and when they bragged about their family’s eminence.’

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Aside from the rooster, who belongs to a deaf nonagenarian, the central protagonist of the novel is Kochukattan, who tries in vain to be the voice of reason. He dreams of going to Saudi; in his head he’s always aboard an aeroplane, even when he goes to the toilet. He worries about the impending changes in landscape: ‘What will I do every morning in Saudi? They don’t have coconut trees, only palm trees.’ His grandfather never believed in ‘a life lived in debt to the gods’, a life lesson that Kochu—neither a Nair or a Nambuthiri—has internalised in good measure.

His nemesis is the phony patriot, Chaaku, who claims to be an army man but is rumoured to be a sackdealer. Chaaku, a paranoid Trump-like figure, lives behind high walls in mortal fear of imagined foes. He celebrates Saddam Hussein’s execution by cooking ‘a nice sweet payasam’ and bursts crackers when America invades Afghanistan. His idea of America is drawn from Hollywood films. The foil is provided by Kurup saar, a village venerable, a former revolutionary who now believes that ‘he has to worship in every puja, from nirmalayam at early dawn to athaazapuja at night’.

At one point in the novel, Unni mentions a sign in a toddy shop warning its customers to refrain from talking politics in the bar. If the writer were present in the bar, he would never be thrown out for breaking this rule. The pub landlord would be fooled into thinking this was a nutty village writer who seemed a little too obsessed with roosters and, perhaps, Calvino’s folktales.

The book is also wonderfully produced, each chapter being preceded by black-and-white illustrations by Riyas Komu. Komu deploys old matchbox covers and simple silhouettes (Sisyphus rolling a boulder) to hint at what lies in store for the reader. J Devika, who translated Unni’s short stories, again gives us a readable translation that at times throws up the odd awkward sentence, which tries to be a little too faithful to the original: ‘Twist and tangle needlessly’; ‘Catching the promise of the promise’; and ‘he knock-knocked on the door’.