The Right Rebels

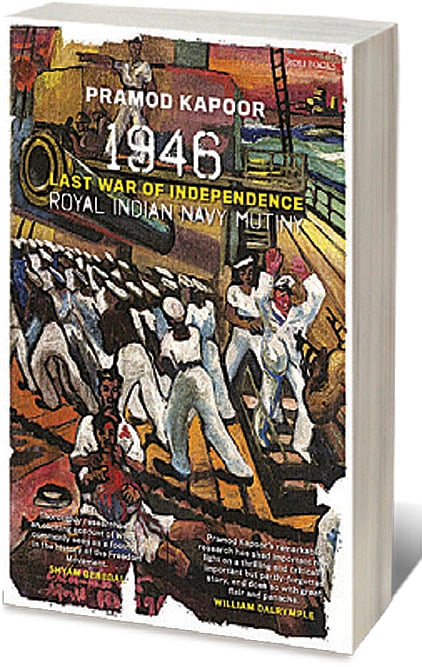

DECADES AGO, I came across Robin Winks’ The Historian as Detective, and was reminded of it when reading Pramod Kapoor’s 1946—Last War of Independence: Royal Indian Navy Mutiny, quite likely the most capacious and unquestionably the most lively account we have of ‘the last war of independence’, or what is sometimes alleged to be the final jolt to the British Raj that perhaps even hastened the end of colonial rule in India. Kapoor, who is the publisher of Roli Books but also has a flair for writing and an eye for detail, has left no stone unturned in his endeavour to research the history of the Royal Indian Navy Mutiny, which erupted on February 18, 1946, in Bombay though the unrest then spread to Calcutta, Karachi, Madras, and elsewhere. He probes archival records, wades through the evidence collected by a commission of inquiry, interviews relatives of the major players, and pursues every lead. His hunt for the ratings who took part in the mutiny—some call it a strike—took him across the country, and his book concludes with a charming epilogue on the “people, places and ship” that populate his narrative.

It is precisely because Kapoor is not a professional historian that he is liberated from some of the unwieldy protocols of the profession, even as he is sometimes prompted into voicing opinions with which complete agreement is difficult. Where in other hands this might have turned out to be a liability, Kapoor sallies forth with a full awareness both of the power of a good story and his own gifts at storytelling. The mutiny lasted but a few days, and he keeps you on the edge with a detailed, almost hourly, account of how the events unfolded, though the tenseness of the moment is occasionally relieved with an ironical observation, a gripping anecdote, and a sprinkling of bon mots. All this is anchored in a larger narrative sketch, which lays out the circumstances in which the mutiny erupted and its reverberations throughout the country, though it becomes clear from the outset that Kapoor is animated by one central consideration. He seeks to restore the mutiny, which he argues has been consigned to a footnote in most histories, to its proper place in the history of the freedom struggle; correspondingly, he elicits the reader’s admiration for the rebels who were not only betrayed by the nationalist leadership but suffered the ignominy of dishonourable discharge from the navy and sent back penniless to their villages on a one-way ticket with a simple injunction: ‘Do not ever come back to Bombay.’ Most of the rebels were never heard from again; they became lost to history.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In its bare outlines, the story of the mutiny is easily told. World War II saw a considerable expansion both in the Royal Indian Navy and the Royal Indian Air Force. In all three services of the armed forces, the end of the war had brought to the fore the problems posed by demobilisation and the poor prospects for gainful employment of men released into civilian life. Still, recruits to the navy were lured with promises of a steady job, good food, decent pay, and the thrill of an exciting job. But working conditions were far removed from this ideal, and the disparities between British and Indian sailors were considerable. Indian sailors not only resented the rotten food, often little more than watery dal peppered with stones, but they also had to face vile racial abuse from English officers. The ‘degrading’ and ‘inhuman’ service conditions aside, many of the ratings, like most Indians, had been moved by the political developments following the end of the war. The colonial state launched a prosecution of Indian officers belonging to the Indian National Army (INA) in November 1945, charging Colonel Prem Singh, Major-General Shah Nawaz Khan, and Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon with murder and “waging war against the King-Emperor.” This was perceived as an outrage to the nation, more particularly because the trial was conducted at a time when negotiations for India’s independence were underway and therefore put into serious question Britain’s intentions, and the massive groundswell of opinion in favour of the accused compelled the British to commute the sentences of the accused who had predictably been found guilty.

However, other INA trials were still proceeding when, on February 18, 1946, the ratings at the Colaba-based HMIS Talwar, a signal school, mutinied. Though the Commission of Inquiry that was later appointed announced that the mutiny was “not pre-planned”, Kapoor’s meticulously constructed narrative suggests otherwise, or at least allows us to say that the truth lies somewhere in between. There was no “outside agency”, but discontent was widespread and the ratings were keen to air their grievances. The food was bad, but as Kapoor narrates it, the intrepid Kusum Nair—later a formidable authority on agricultural practices in India, Japan, and the United States—who was involved in the “plot” ensured that small stones were placed in the dal on the 17th night “in order to enrage and instigate all the ratings into open rebellion”. That the disaffection against the British went back many months is illustrated by the fact that the senior telegraphist on HMIS Talwar, Balai Chand Dutt, whose memoir is a key source, engineered to have the parade ground on December 1, 1945, when the city’s ship and shore establishments were going to be displayed to the public, sprayed with signs—“Quit India”, “Kill the British”, “Down with the Imperialists”, “Revolt Now”—clearly intended to humiliate the British.

There would be many other little acts of insurrection on HMIS Talwar over the next several weeks and on February 18 the ratings finally threw the gauntlet to their superior British officers. That day, Arthur King, Commanding Officer (CO) of the ship, hurled abuses at them, describing them as “Sons of Bloody Junglees”, “Sons of Bitches”, and “Sons of Coolies”. Over 100 pages, Kapoor describes how the mutiny spread from one ship to another and to shore establishments, and to naval stations at other cities. The mutiny at its height involved 20 shore establishments,

over 75 ships, and 20,000 sailors; according to Kapoor, the correspondence of Prime Minister Clement Attlee and the Viceroy, Archibald Wavell, points to the “fright and panic that had set into the British administration”. The navy lay at the heart of the British Empire; moreover, there was a palpable fear that the unrest might spread to the other services. Airmen at the Royal Indian Air Force station at Karachi had already struck in January, but the unrest, no doubt spurred in part by the naval strike, would spread through February and beyond to over 50 other air stations in India and even Southeast Asia and West Asia. The British were inclined to use heavy force to subdue the mutineers in Bombay and adopt a “take no prisoners” approach. Kapoor tells us that at one point, incensed by Admiral Godfrey’s threat that he was prepared to countenance “the destruction of the navy” but would not tolerate insubordination, the ratings had “trained their guns from the ships towards Gateway of India and the Yacht Club”, but he argues that this “was purely a defensive tactic” intended “mainly to target the British troops being amassed in that area”.

The ratings who struck at Bombay formed the Naval Central Strike Committee that issued a set of demands which suggests that these subalterns were politically astute and thought beyond their own grievances. Besides asking for better food, working conditions, and respect—and this call to be treated with dignity should always resonate—they also called for the release of all INA prisoners, withdrawal of Indian troops from Indonesia where they were being used to thwart the legitimate political aspirations of Indonesians, and employment for demobilised men. Meanwhile, the strike had attracted extraordinary support throughout the city, and newspaper accounts and testimonies from those days point to unusual scenes of fraternisation among the striking sailors and Bombay’s citizens. Food was freely distributed to the ratings and shopkeepers refused to accept payment. Students, labour activists, mill workers, and others were forthcoming in their assistance to the rebels and called for a city-wide hartal, and British efforts to subdue crowds led to police firings and violence in the streets. By the end of day on February 22, over 60 people had been killed; the following morning’s Hindustan Times had a headline that ran across the length of the paper, “Bombay in Revolt: City a Battlefield”. The same day, however, much to the shock of the ratings, the strike committee’s leadership capitulated to the demand, not only by the British but by the Congress leadership, that the strike be declared over. The ratings surrendered, on the understanding, delivered by Sardar Patel, that they would not be penalised.

“WHEN AURORA ZOGOIBY”, the fictional character in Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh, “heard that the Naval Strike Committee had been persuaded by the Congress leadership to call off the stoppage . . . her disappointment with the world at it was burst its banks. . . . she was thinking the same things [as the defeated sailors]—that the Congress were acting like chamchas, toadies. . . . When the masses do actually rise up, she thought, the bosses turn tail. Brown bosses, white bosses, it was the same thing.” That the pledge to the ratings was not honoured is, as Kapoor rightly points out, a matter of disgrace and shame to the nation. Neither the Congress nor the Muslim League was supportive of the strike; the communists alone, in his narrative, come out with flying colours. The position of the communists at this juncture was, however, more complex than Kapoor’s analysis suggests. Their refusal to support the Quit India movement had discredited them, and they had much ground to recover; on the other hand, a more holistic view of communist politics in 1945-46 would entail a consideration of the Tebhaga movement in Bengal, the Telangana Rebellion in Hyderabad state, and other forms of unrest that would give us a more nuanced view of the communist support of the naval mutiny.

With regards to the Muslim League, the reader will find priceless Kapoor’s recounting—drawing upon retired Pakistani Rear-Admiral Mian Zahir Shah’s book, Bubbles of Water, or, Anecdotes of the Pakistan Navy—of the meeting that transpired between the Muslim rebels and Jinnah on February 21, the third day of the mutiny. Only minutes into the meeting the ratings and petty officers, who had shared with the Quaid-e-Azam their grievances, realised that he was “not in favour of them going on with the mutiny.” There remained little to talk about; however, an hour had been allotted for the exchange, and everyone made small talk. As the conversation was drawing to a close, Jinnah asked the ratings, “By the way, what are you all wearing?” One rating replied, “Uniform, sir.” “No,” said the Quaid-e-Azam, “this is not uniform, since a uniform means ‘ek jaisa’ and implies uniformity.” “You call this uniform? Some are wearing khakis, some whites; some shorts, some longs; some shoes, some boots. Remember, uniform is a sense of discipline; and without discipline there can be no welfare.” The men looked at one another and thought to themselves, “The Quaid was worse than their CO!” As his visitors prepared to leave, the Quaid added, with a far-away look, “I would want uniform, and discipline, in the Pakistan Navy.”’

We may reasonably infer from Jinnah’s remark the reasons why the Congress, and particularly Jawaharlal Nehru, Maulana Azad, and Sardar Patel, could not bring themselves to support the strike and prevailed upon the rebels to throw in the towel. Kapoor is somewhat more tolerant of Gandhi, since, as he often states, both the Mahatma’s aversion to violence and his rigid insistence that the use of violence was antithetical to the idea of swaraj are unimpeachable facts and one expects that Gandhi would not have been supportive of the strike. It is the attitude of the other Congress leaders, however, that clearly disturbs him and moves him to critique them for their pusillanimity and betrayal of the ratings who had not only displayed exemplary bravery but whose own display of Hindu-Muslim unity was precisely the ideal otherwise held up by the Congress. Kapoor accepts the view put forward by some historians, namely that the Congress was generally opposed to political movements that had not originated within the party or that it could not control. Patel was convinced that “the communists are intent on working up a state of chaos”, but Kapoor, while recognising that the Congress leadership viewed the communists as opportunists, does not pursue this line of inquiry. He veers rather to the view that “sensing a transfer of power and imminent independence, the Congress did not want to rock the boat at this critical juncture. So the Congress leaders were bent on persuading the ratings to remain peaceful and surrender unconditionally, giving them assurances that were well beyond Congress’ capability to deliver.”

One might reasonably aver, as does Ashis Nandy, that Kapoor’s “book is a challenge to us to take a second look at our revered political figures whose charismatic public presence often hid their own insecure ruthlessness and narcissism, both leavened with a touch of hypocrisy.” Or, to put it simply, the humble ratings were thrown to the wolves. The “evidence” seems to support such a reading, but Nandy, as much as anyone else, understands the unforgiving logic of the nation-state. Patel later defended his objection to the strike with the observation that “discipline in the Army cannot be tampered with . . . We will want the Army even in free India.” India was not yet free, but it was on the verge of independence, and Nehru and Patel were committed to the idea that civilian control over the military must always remain an inviolable principle of a democratic state. One suspects that, from their standpoint, condoning the action of the mutineers would establish an unhealthy precedent and certainly did not augur well for “military discipline” in what was poised to become free India. It is striking, as Kapoor himself notes, that “Indian navy officers did not, or perhaps could not, back the ratings and they stayed loyal to the Royal Indian Navy.” He goes on to argue that in independent India most of them went on to have very distinguished careers in the navy and their “devotion to their country remained beyond reproach.” Surely, however, given the ardour with which he supports the ratings and berates the Congress leaders, Kapoor might have reflected more on why Indian officers did not lend their support to the mutineers. Were they merely selfish in wanting to protect and advance their own careers in independent India? Or were they mindful of the implications of such a mutiny for navy discipline after independence? Or is this yet another illustration of the difficulties of forging solidarity across class barriers?

Nevertheless, it is comforting to think that, even if momentarily, Hindus and Muslims were able to overcome their differences and find common ground. At this present moment, Kapoor’s book is a superb reminder not only of the importance of an event that has been occluded from the national imagination, and equally of a time when awareness of oppression trumped religious differences, but also of the possibilities of the transgressive force of truly revolutionary activity.