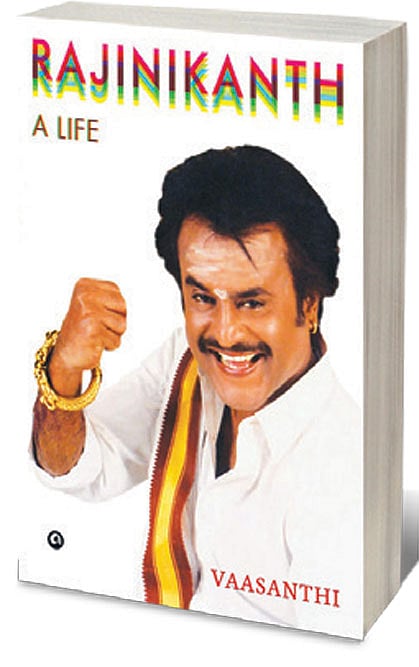

The Rebel Model

LIKE MOST STORIES about Rajinikanth, Vaasanthi’s, too, opens with a young Shivaji Rao Gaekwad caught in the riptides of hunger and haplessness. Despised by his father, a retired police constable, for being an insubordinate wastrel, he seeks solace in the kindness of his friends and his brother, and finds sustenance and spirituality at the Ramakrishna Mutt where he attends evening classes. Vaasanthi’s story takes flight where others have sputtered to a stop before. Her extensive interviews with Ravindranath, Ashok and Raghunandan, his friends at the Madras Film Institute who gave him food, shelter and emotional relief—and have continued to advise him through much of his life as a superstar—throw up insights into his personality that often knock the reader off the stoop of certainty.

Beneath the carapace of the ruffian who does not bother to wash or dress well, and ransacks the store room of the Woodlands Hotel in Chennai leading his friend who works there to lose his job, is a man who clings to the lifeline that is cinema. But this is no plain, inspiriting, rags-to-riches saga. How did a character actor who started out playing villain for K Balachander, won a best villain award a decade ago for Enthiran (2010), and evoked Ravana in Pa Ranjith’s Kaala (2018) become “the invincible god on the screen”? “His strength came from the fans just as a stone gets its divinity from the collective devotion of the faithful. The words he uttered on the screen became mantras for the fans. Even before the release of the film, they were eager to hear the punch lines,” Vaasanthi. She probes the fund of passion and ambition that powers his characters, and his “descent into violence and a desperate need to keep working between 1977 and 1979” that coincided with some of his best performances, including in SP Muthuraman’s Bhuvana Oru Kelvikkuri, Bharathiraja’s Pathinaru Vayathinile (1977), and M Bhaskar’s Bhairavi (1978).

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Rajinikanth is not a clean-cut hero either on screen or in real life. “His art and life were inseparable from cigarettes and alcohol,” Vaasanthi notes. From losing his job as a bus conductor in Bangalore for trying to make money by not issuing tickets to slapping journalists who turned up uninvited to his wedding and considering a divorce that would set him free, he is far from a role model. He is not self-consciously sui generis; rather, by playing characters who, like him, are not all black or white, he seems to empathise with everyone who has had a hard life.

With fame and wealth, however, came shackles and expectations to play to the gallery. When he bought a house in Chennai, “he did not use the many things that surrounded him”. “There was a tennis court in the house, but he didn’t know how to play the game. There was a swimming pool and he didn’t know how to swim. This life felt heavier and more burdensome than the heaviest paddy sacks he had carried.” Spiritual retreats calmed him every time he was at the end of his tether. Could politics have filled the void? His flip-flops on Jayalalithaa, whom he first condemned as a corrupt despot and later befriended, on the Cauvery water-sharing dispute between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, and on the BJP revealed him to be an immature political player. His reliance on a coterie of advisors, his innate reluctance and indecision, and his age and health did not bode well for a plunge into politics. Who was the real Rajinikanth, Vaasanthi asks, in one of many reveries on his life—“the working-class mass leader that he portrays on screen or Rajinikanth, the politician, who admonished the young men who disobeyed the police during the IPL cricket match in Chennai, or the one who made statements that anti-social elements had infiltrated the anti-Sterlite agitation after the police opened fire and killed thirteen people in Thoothukudi (Tuticorin) on 22 May 2018”? Whatever he may be, Rajinikanth, by relinquishing politics, has proved he is not a high-stakes gambler tempting fortune to the end.