The Questioning Self

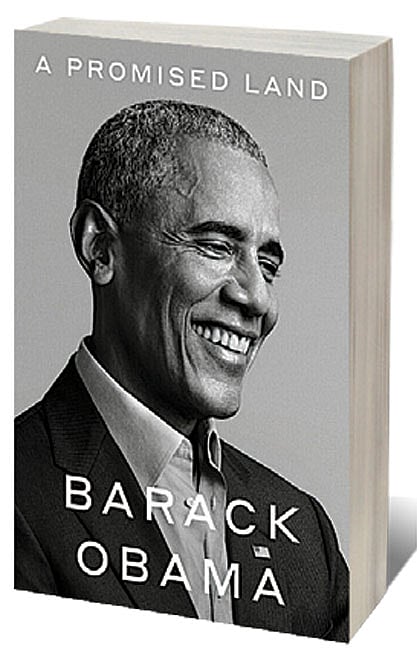

A SPIRIT OF INQUIRY, self-questioning and debate binds the first volume of Barack Obama’s presidential memoir. A Promised Land takes the Obama story from his birth in Hawaii up to May 2011, when American forces killed Osama bin Laden in his hideaway in Pakistan’s Abbottabad.

The timeline also neatly bookends aspects of identity that have been integral to Obama’s personal life and politics—it starts with his birth to an American woman and a Kenyan man, and carries right to the annual White House Correspondents’ dinner, the night before the bin Laden operation, when ‘the audience howled’ at his public ‘ribbing’ of Donald Trump, then already seen to be considering a run for president having attracted media attention with his vile and racist questioning about Obama’s birth certificate.

Obama has spent his adult life talking about, and having others write about, the specifics of family circumstances that informed his politics and public aspiration, and, as he writes in the preface here, it propelled the ambitions behind A Promised Land too. He wanted, he writes, ‘to tell a more personal story that might inspire young people considering a life of public service: how my career in politics really started with a search for a place to fit in, a way to explain the different strands of my mixed-up heritage, and how it was only by hitching my wagon to something larger than myself that I was ultimately able to locate a community and purpose for my life’. In addition, as he says in the preface, this memoir was being written at a time when ‘someone diametrically opposed to everything we stood for had been chosen as my successor [as President of the US]’.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The form of autobiography has long been Obama’s way of explaining his way in the world and equally the frame for him to articulate ways to understand issues and explain them. But it is the rise of a majoritarian politics—seen not just in the rise of Trumpism in the US, but in diverse variants worldwide—that gives the Obama template of embracing mixed-up heritages on a capacious political platform an urgent salience.

That, suggests Obama in A Promised Land, means striving to see every situation from the other person’s perspective and to constantly question one’s own perspective. Early lessons came from his mother, a feminist and civil rights activist who worked on microlending programmes in Southeast Asia, when she pulled him aside after he had been part of a group who’d teased a fellow student. He recalls the conversation that’s stayed with him: “You know, Barry, there are people in the world who think only about themselves. They don’t care what happens to other people so long as they get what they want. They put other people down to make themselves feel important. Then there are people who do the opposite, who are able to imagine how others must feel, and make sure that they don’t do things that hurt people. So, which kind of person do you want to be?”

The answers to that question have many aspects—of race, as the son of a Kenyan father he hardly knew and brought up by his white Midwesterner maternal grandparents; of class, especially during his years in Indonesia when his mother married an Indonesian; of ambition, as he threw himself amid books, working his way to Columbia University and later Harvard Law School; of fraternity, as he spent the rest of his life finding anchors in public purpose, in community work in Chicago and later in bids for high office.

In a passage that is particularly poignant for its hint of the loneliness that may have sometimes held together this life story, he speaks to his younger self at Columbia in New York City in the early 1980s, living a monk’s existence, reading, writing and thinking of how social movements succeed or don’t, not blinking away from a ‘regimen of self-improvement’. He writes: ‘When I look back on my journal entries from this time, I feel a great affection for the young man that I was, aching to make a mark on the world, wanting to be a part of something grand and idealistic, which evidence seemed to indicate did not exist… If I were to travel back in time, I might urge the young man I was to set the books aside for a minute, open the windows, and let in some fresh air (my smoking habit was then in full bloom). I’d tell him to relax, go meet some people, and enjoy the pleasures that life reserves for those in their twenties.’

But the tide of self-improvement and finding community had its own momentum, as he shifted to Chicago, taught law, ran for office—first in the state legislature and then the US Senate, and finally in no time, with little experience at the national level and really just his life story, for the White House. Each step appeared to nominate him, double time, for the next bid. ‘It’s like you have a hole to fill,’ his wife Michelle had told him early on. ‘That’s why you can’t slow down.’

The constant self-interrogation gives the reader vantage points to view Obama’s domestic and international record as president. But the memoir is made more powerful by the quieter moments it captures—the time he finally ‘allowed’ himself to cry after clarifying issues of race raised by a sermon by his pastor Jeremiah Wright. Or the time a Black Harvard professor was handcuffed and booked by the police while trying to force open the jammed front door of his own house, prompting Obama to ‘almost involuntarily [conduct] a quick inventory of my own experiences’.

And the time he caught a moment of kinship at a state dinner in Delhi with the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, whom he describes elsewhere as ‘a thoughtful and uncommonly decent man’. ‘In uncertain times, Mr. President,’ said Singh, ‘the call of religious and ethnic solidarity can be intoxicating. And it’s not so hard for politicians to exploit that, in India or anywhere else.’ Writes Obama: ‘I nodded, recalling the conversation I’d had with Václav Havel during my visit to Prague and his warning about the rising tide of illiberalism in Europe.’

That rising tide was evident in the US too. On the eve of Obama’s inauguration as America’s first Black president in January 2009, John Lewis had said: “Barack Obama is what comes at the end of that bridge in Selma [where a civil-rights march in 1965 had been brutally attacked by state troopers].” But a couple of years later, in Obama’s words, ‘more and more, I’d noticed how the mood we’d first witnessed in the fading days of Sarah Palin’s campaign rallies and on through the Tea Party summer had migrated from the fringe of GOP politics to the center—an emotional, almost visceral, reaction to my presidency, distinct from any differences in policy or ideology. It was as if my very presence in the White House had triggered a deep-seated panic, a sense that the natural order had been disrupted.’

Obama writes that the plan for the memoir was for it to be ‘maybe five hundred pages’ and ‘be done in a year’ after he left office. The delay allowed him to situate the first volume amid the raging pandemic whose transformative effect, if any, is not yet clear; and the length means the final appraisal of A Promised Land must necessarily await the publication of the second and closing volume, that will cover the greater part of his presidency, and hopefully the years after too.