The Philosopher Who Would Be King

SOMETIME IN 1655-1656 Dara Shukoh had a vivid dream. He found himself face to face with Rama, Lord of Ayodhya, and the sage Vashishtha. The preceptor goes on to say, ‘O Ramchandra! This is a disciple who is absolutely sincere, please embrace him.’ The king embraces Dara ‘with utmost affection’. Sweets are passed by Vashishtha and the Mughal partakes of them happily.

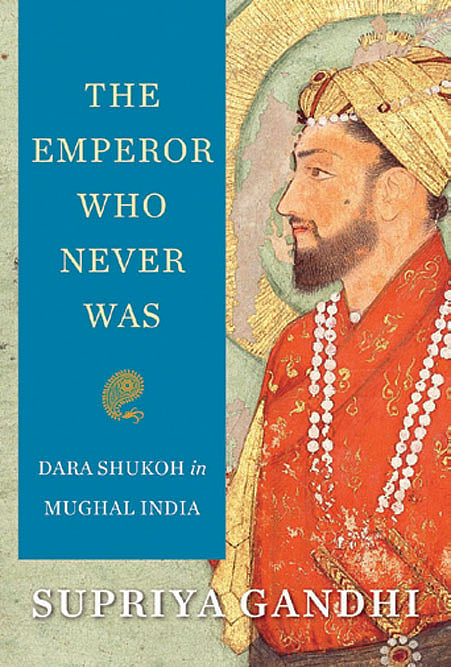

Those years were probably the happiest for Dara and in a sense marked the culmination of his life’s quest. In the months ahead, the prince and the learned men around him completed a new translation of the Yogavashistha, a dialogue between Rama and Vashishtha. In The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India (Harvard University Press; 338 pages; Rs 699), Supriya Gandhi notes, ‘By translating the Laghu Yogavashishtha anew, Dara Shukoh claimed the text for himself. Its argument that a prince could achieve full self-realization as an ascetic while acting as an exemplary ruler spoke directly to his own situation… To translate a text that had been in India far longer than one’s celebrated ancestors was to sprout deeper roots in the subcontinent’s soil.’

Dara’s ambition did not end there. In 1657 he commenced the translation of a selection of Upanishads culminating in his work the Sirr-i Akbar or ‘The Greatest Secret’, a work that was breathtaking in its scope. The prince thought of it as a key to bridging Islam and Hinduism: ‘It is a noble Quran, in a hidden book (kitab maknun), which none save the purified touch, a revelation from the Lord of the Worlds.’ This is followed by a neat mapping from the Hindu pantheon to Semitic angels. Brahma becomes archangel Jibril (Gabriel); Vishnu, the angel Mikail (Michael); and Mahesh, the angel Israfil.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Whatever one may think of this freewheeling theological exercise, its political import was clear. It is not uncommon to see comparisons between Akbar and Dara as tolerant Islamic rulers who attempted to bridge their religion with that of whom they ruled. These comparisons are usually based on the innate qualities of the two Mughals. In terms of political achievement, however, what Dara did was bolder and ultimately tragic for the prince. Akbar began his experiments on religious toleration with a clean slate after consolidating his military gains. His project was based on the realisation that one could not rule a country with an alien religion, different from the one of the rulers, merely by repression. In time the ulema were brought in line and never allowed to dominate the state. In Dara’s case, an Akbarian rejuvenation approached the limits of what was possible. In the half century since Akbar’s death, Islamic orthodoxy not only re-acquired strength but even gained an upper hand. Both Jahangir and Shah Jahan were, at best, indifferent to ideological projects of tolerance.

It is not proper to compare ideas and modes of rulership using current ideas. A methodological barrier separates the two worlds and gleaning the past through the lens of the present is, at best, flawed; at worst, meaningless. That is one reason why contemporary ideas of secularism defy a translation into tolerance as it existed in medieval India. That, however, does not prevent a dream-like counterfactual exercise: What if Dara had succeeded? The motive is understandable especially when contemplated from the vantage point of contemporary liberalism. This can be ruled out right at its base.

Consider Dara’s situation in 1657. He was Shah Jahan’s designated heir. At the imperial court he enjoyed immense prestige and wielded extraordinary power. His interactions and discipleship with influential Sufis of the age—the dervish Mulla Shah being foremost—propelled his religious-political project sufficiently in the direction that he wanted. This was both in its personal dimension and in terms of how he imagined his impending rulership of India. But an Akbarian equilibrium required another ingredient, one that Dara had virtually none of: ability as a military commander and governor.

By the time Sirr-i Akbar was completed, Aurangzeb—Dara’s younger brother—had been the governor of Dakhan for a long time. The administrative experience of the younger prince was largely in the Empire’s most troubled and frontier provinces: Balkh, Kandahar, Dakhan. In contrast, Dara had spent the most of his life either in the court or in pacified provinces. His experience in difficult regions—for example, Kandahar—did not suggest military acumen. While Aurangzeb had to earn every instance of rank and title that he received; Dara acquired the lofty title Shah-i-Buland Iqbal with an extraordinary rank of 50,000 infantry and 40,000 cavalry almost effortlessly.

The result was a marked gap between his ideas for ruling India and his actual ability to do so. In 1658, as Shah Jahan faded away, this became obvious even to his camp followers. One example that Gandhi highlights is the conduct of Jai Singh—the general sent to quash prince Shuja’s rebellion in East India—who simply disappeared even as Dara sent him frantic messages to bring his army back. At Samugarh (May 29th, 1658), Dara’s army simply melted away. Jai Singh went on to work under Aurangzeb. Fate caught up with Jai Singh and he faced a denouement for his alleged role in the escape of Shivaji from Agra.

Such is the force of Gandhi’s book that one cannot but dream on. Given the absence of primogeniture in Mughal India, wars of succession were not only messy and complicated but were also a matter of chance. Three decades earlier, when Khurram, as Shah Jahan was then known as, rebelled against Jahangir; his rebellion came to an end in 1626 when he was cornered. Retiring to Balaghat—today a thickly forested district at the edge of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh—the prince begged forgiveness. He was given one and for all purposes his career was at an end. But then fate intervened as Mahabat Khan—the disgruntled general who had chased him—effectively made Jahangir and his queen prisoners near Lahore. That set in motion a chain of events leading to the death of Jahangir and the installation of Sharyar as the next Mughal. But in three months, he met a grisly end on the command of Shah Jahan. This was the result of a complex and unpredictable chain of events whose end no one knew. (For example, what if Mahabat Khan had not acted rashly? What if Nur Jehan had sufficient time to firm Shahryar’s grip on the empire?)

Even this stretches one’s imagination. Khurram had spent a great part of his life in camps and campaigns across the length and breadth of the empire. That gave him experience that Dara never accumulated. So, when the new war of succession began in late 1657, chance played its role but Dara was the most ill-prepared and ill-equipped prince seeking the throne in at least two generations of Mughals. His fate, even if it was not pre-ordained, was by and large, determined by earthly factors.

All this is no reason—there are none at all—not to enjoy Gandhi’s book. If you are in Delhi, take your copy to Humayun’s tomb. As you go straight from Bu Halima’s enclosure to the magnificent building that encloses the second Mughal’s cenotaph, on the left at the end of the flight of stairs lie unmarked sarcophagi. With some effort one can guess which one belongs to Shah-i-Buland Iqbal. On a good day there is a gentle breeze on that elevated platform. It is a good place to speculate what India could have been under this very different prince.