The Maximalist

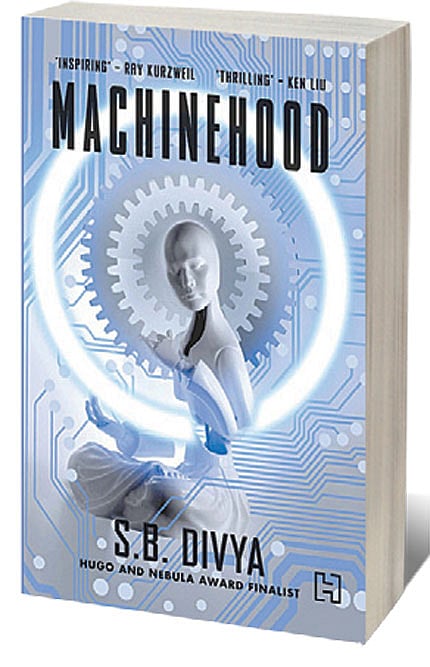

AMERICAN LITERATURE has given us a few outstanding “office novels” over the last couple of decades; Then We Came to the End (2007) by Joshua Ferris comes to mind immediately (it’s named after the opening line of Don DeLillo’s 1971 novel Americana, another accomplished critique of American corporate life). An office novel is ideally placed to give the reader a holistic, bird’s-eye view of how capitalism is affecting society, both at the macro and micro-levels. The changing nature of jobs implies, of course, the changing nature of lives, of families, of entire societies. And if you like that kind of gradually expansive narrative structure, you have to read SB Divya’s novel Machinehood (Hachette; 416 pages; ₹ 499) published in August last year and nominated for a Nebula Award recently. Divya is the first writer of South Asian origin to be nominated for a Nebula award for best novel, which was started in 1965 and is one of the most coveted awards for science and speculative fiction.

A maximalist book in more ways than one, Machinehood is dizzyingly ambitious and juggles several complex, weighty themes across its 400 pages. But at its heart, it’s about two closely related issues in the year 2095—the widespread usage of pills to enhance human performance (“zips” for speed, “buffs” for strength and endurance, “flows” for focus and cognitive abilities) and the gig economy, where humans now compete with increasingly efficient AI (artificial intelligence). The pills are partially a way to block the potent superbugs Earth is cursed with circa 2095—and partially a way of ensuring that humans stand a chance of being hired over AI for gigs (even if the gig is to babysit an AI as it does the work).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

When a hitherto unknown terrorist group called the Machinehood starts killing major pill funders across the planet, the novel’s protagonist Welga, an ex-Special Forces-soldier-turned-bodyguard, reluctantly works with the US government again (their political gamesmanship has hurt Welga in the past) to bring them down. Talking about the novel during a Zoom interview, from Southern California, Divya explains how the novel tackles some very real issues facing humanity in 2022—including the question of what one is legally (and, perhaps, morally) entitled to do with our own bodies.

“I think that choice is something we are going to see more and more of,” says Divya, who was born in Pondicherry, and immigrated to the US with her parents when she was five. “Especially as biotechnology becomes increasingly prevalent in our lives, not just in terms of cybernetics but also gene therapy, genetic engineering and medical technology. All of these things involve an interaction between your personal autonomy and what society sees as harmful. And so as we have greater abilities to change our bodies, we will confront this question again and again. When something goes wrong, we will also ask ‘who bears responsibility for this choice’?”

Machinehood is set 70-odd years from today, and within these seven decades, human beings try both pills and cybernetic enhancements to try and compete with AI for gig work. There are periods of deregulation, during which people go too far (with pills or cybernetics or both) and suffer the consequences— the wrong kind of pill in the wrong kind of body results in painful death, and overuse of cybernetics eventually starts killing the organic parts of the user’s body.

Divya explains, “I think that throughout history, progress around these issues—especially sensitive issues of bodily autonomy like medicine or technological enhancements to the body or even abortion, which is a subplot in the novel—tends to happen in cycles. We make strict laws, people find a way around those laws and then those laws are relaxed which sees some people making choices that sometimes prove to be harmful (or are perceived that way by society), because of which we again introduce greater regulation. Two steps forward, one step back, that kind of thing. It’s almost like physics where every action has an equal and opposite reaction. In the novel I try and show how this process could have happened between now and 2095.”

Obviously, there are parallels with some real-life red-button situations in American society—most notably, the opioid crisis. In Machinehood, Welga’s sister-in-law Nithya (the two of them are the only characters in the book with point-of-view chapters) is investigating why the former is exhibiting muscular spasms immediately after taking “zips”. She suspects that the pill manufacturers may be hiding certain side-effects of the “zips”. This can be read as a reference to the 2018 revelation that a particular pharma company knew its opioid painkiller OxyContin was highly addictive and the company actively suppressed this information.

At the beginning of several chapters in Machinehood, there’s a brief extract from the self-explanatory ‘Machinehood Manifesto’, which critiques the cut-throat, grossly inequitable nature of the gig economy. For example, the missive at the beginning of Chapter 2 says: “Modern society has found itself at the mercy of an oligarchy whose primary objective is to accrue power. They have done this by dividing human labor into two classes: designers and gigsters. The former are exploited for their cognitive power, while the latter rely on low-skilled, transient forms of work for hire.”

During the interview, Divya says that while researching for Machinehood, she studied a number of famous manifestos throughout human history, ranging from the Communist Manifesto and the UN Declaration of Human Rights to the Unabomber Manifesto written by mathematician Ted Kaczynski. “Manifestos have immense power in that they can influence thought easily,” says Divya. “But it is much trickier to influence human behaviour across a short time-span. It is difficult to change your behaviour patterns overnight, especially when your livelihood depends on them.”

While reading Machinehood the text I was most often reminded of was American professor Donna Haraway’s landmark 1985 essay ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’, originally published in Socialist Review. In this essay, Haraway criticised what she saw as society’s anthropocentrism and rejected our too-rigid definitions of “human” vs “animal”, as well as “human” vs “machine”. According to Haraway, these “antagonistic dualisms” are an inevitable result of traditions like patriarchy, colonialism, naturalism and so on (“grammar is politics by other means,” Haraway writes). She encouraged feminists to look beyond these binaries into a post-human future where the ‘cyborg’ framing represented a new animal-machine hybridity, one that allows us to build a new feminist politics free from the linguistic (and therefore political) remnants of the oppressive past.

“I did spend some time researching ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’ while writing the Machinehood Manifesto for the novel,” Divya says. “It was born out of the feminism of its time (1980s) and its desire to break free of the shackles of society. I’m definitely a feminist and I would also call myself a technologist in general. I don’t believe that technology is a panacea or that it can solve every one of our problems. But I do think it is an effective tool that has helped us humans take over the world. Whether or not that’s a good thing is one of the dilemmas explored in Machinehood.”

Some of Divya’s past works, like the titular story from her 2019 collection Contingency Plans for the Apocalypse and Other Possible Situations, or the novella Runtime (2016), have also featured characters with cybernetic enhancements like the kind Welga has. We are told that this is routine for US government soldiers as well as those engaged in “shield work” ie the showmanship-laden version of personal security circa 2095, where cameras follow the guards everywhere and strangers on the internet pay to watch the fistfights via “tips”.

The cybernetic enhancements bit draws from the author’s own scientific background—Divya was a part of an interdisciplinary department at Caltech called Computation and Neural Studies, which had elements from disciplines like computer science, machine learning, electronics and neuroscience. Before becoming a full-time writer (which she currently is) Divya worked for over two decades as an electrical engineer. She holds two patents that contributed towards the development of the modern-day pulse oximeter—a device whose importance has, obviously, grown significantly since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Divya says, “If you’re in the ICU or under sedation, you really need devices like the pulse oximeter to keep track of your oxygen levels. But in these weakened states, the finger often slips off the device, so one of my patents was with a firm that was developing the tech that alerts you to situations like that.”

Clearly, Divya’s diverse life experiences have contributed to how well-rounded her works are, incorporating and interrogating viewpoints held by scientists, politicians, social workers, the rich, the poor and everyone in between. Her treatment of the gender spectrum is also solidly progressive and matter of fact (Divya identifies as genderfluid herself). A prominent character in Machinehood is a trans man and the usage of they/them pronouns has been normalised around the world by 2095. In the past, too, Divya’s stories have featured queer and nonbinary protagonists (like Runtime, which had third-gender pronouns and nonbinary characters). During the interview, I ask her about the significance of writing decidedly progressive science fiction at a time when this progress has seen a loud and persistent brand of organised pushback from white conservative science fiction readers in America.

Divya replies with equanimity, “I suspect that the pushback to progressive science fiction is a dying gasp from regressive elements, much in the way we’re seeing in global geopolitics. It’s another example of the two-steps-forward, one-step-back dance. Overall, the stories and books I see in science fiction have embraced a more progressive view on gender, sexuality, and race relative to the classic works, which were dominated by white, cis-male, heterosexual authors and protagonists. I credit the internet in part, because it’s made the submissions of manuscripts from all over the globe much easier and far less costly compared to print and mail.”

Machinehood deserves all the applause it’s receiving today. Part of the reason is its radical rethinking of the nature of human (and machine) labour. This is why towards the end of the interview, I had to ask Divya about how the major economies of the world are adapting to the changing realities of the workplace—not just AI replacing humans but also gig work replacing traditional, protectionist models of employment.

“I worry about the treatment of labour today, and I think we’re going to need to come up with some radical changes (like free college or universal basic income) in order to reshape society to handle the technological developments of the upcoming decades,” Divya says.