The Many Costs and Benefits of the Gig Economy

You are making a cake, you have all the ingredients lined neatly on the counter. You sieve together the flour, salt, baking soda and cocoa. You break one egg into the bowl, and then the second egg, only to realise that the second egg is discoloured and rotten. The oven is already on and heating up. You need new eggs, and you need them now. You turn to your phone, press an app and by the time you’ve powdered the sugar and greased the baking tray, the doorbell rings and you find six fresh eggs at your doorstep. You’ve barely noticed the face of the man who has left it there.

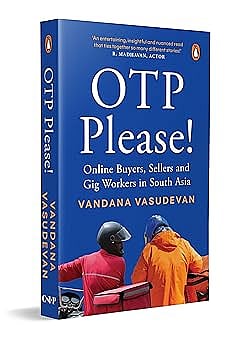

We’ve all been privy to this or similar scenarios where we’ve counted on groceries to arrive in 10 minutes. We are driven solely by convenience and efficiency, we pay little, to no, heed to the ‘backend’. How do these groceries land at our door in the time it would take for us to essentially extract our car from the parking lot and drive down to the local store? Who are these men (the vast majority are men) who weave through traffic at frightening speeds to bring us our coffee before it turns tepid and a pizza for our midnight cravings? What are the human costs of our convenience? Who gains and who suffers in these daily interactions? These are just some of the questions that Vandana Vasudevan addresses in her new book OTP Please.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

As a development-sector researcher and journalist, Vasudevan is well equipped to deal with these questions and to unpack the gig economy at large. In OTP Please, she broadens her ambit beyond India and includes Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh. While the obvious way to structure this book would have been into ‘Customers’, ‘Workers’ and ‘Sellers’, she chooses a more innovative approach by creating different sections around emotions. So, we have Pleasure, Guilt, Gratitude, Anger, Freedom, Oppression, Anxiety, Isolation and Courage. This touchy-feely approach ensures that readers get a diverse understanding of the subject.

In India there is a clear demarcation between those who use these apps and those who provide the services. Vasudevan quotes Kishore Biyani (founder of Future Group)’s definition of the consuming class or those who can afford discretionary expenditure. According to Biyani, anyone who has domestic help is part of the consuming class and he pegs the number at 10-12 crore people in India, which is only 7.5-8.5 per cent of the country’s population. It is useful to realise that we are part of this consuming class, which in percentage is low, but in sheer numbers is massive.

Since the book is structured around sentiments, in the Pleasure section, for example, one reads all the benefits of the various apps both for customers and workers. Vasudevan also notes, “Platforms have been transformative for women workers, both financially and psychologically.” Beauticians at Urban Company, for example, can now consider building a nest egg for themselves as they’ve control over their own money.

But the Pleasure and Gratitude that workers might initially feel soon turns into something much more negative. Vasudevan meets key union workers through the course of the book. The story of Kamaljeet Gill, national secretary of the Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT) is especially poignant. He talks about how the early promises of Uber came to naught after 2017, and how drivers who had mortgaged their wives’ jewellery to buy cars, soon realised that they can barely pay the monthly instalments.

Through Gill and other such impassioned leaders one learns that the dream sold to gig workers— of ‘flexible hours’ and being ‘independent contractors’—rings hollow. According to a survey, 85 per cent of drivers/riders work more than eight hours a day. Being a rider is not an aspirational job, no one wants their children to pursue the same. As Vasudevan writes simply, “No one respects a delivery boy.” Companies and multinational behemoths treat them like a resource and not humans. For example, a driver for Porter says that those who display a Porter poster are told they will get an order ten seconds prior than those who don’t. The algorithm is constantly being tweaked to maximise profit regardless of the human cost. The rating system is built mainly for the benefit of the consumer and a bad rating can lead to the blocking of a worker’s ID. Workers complain that they sometimes get a poor rating because the customer is in a bad mood. This lapse leads to them losing their source of income, which highlights the system’s terribly skewed balance of power.

Sixit Bhatta, the creator of a ride-hailing app in Nepal, explains the shrewd working of the algorithm. “When a platform enrols new riders, it wants to change their behaviour, you want to get them into the system by giving them 200-300 trips and get the dopamine going. Once they are used to it, they get into the same pool of oldies. No one cares about the people in the system because the company knows they are not going anywhere. Even if they quit, there will be others.”

The ploys of companies to maximise profits is best witnessed at an Amazon warehouse. While the machinations of Amazon are well known it is still horrifying to learn that workers must start at 8.30am and continue for 10 hours, with only two washroom breaks of 30 minutes, which also includes lunch and tea breaks. The warehouses have no chairs, and workers often walk around 15km a day stocking and packing items. Amazon’s unfair practices also jeopardise the livelihood of small businesses, as is well documented.

Towards the end of the book, Vasudevan raises the crucial question—can countries rely on gig work to help employ their rapidly increasing working-age population. And the short answer is No. A gig worker is essentially doing a low-skilled job. People choose this line of work because of a lack of options. It is a lonely and relentless job which denies workers the benefits of community and relationships. Importantly, app-based companies are often yet to become profitable so the work is tenuous.

While these apps are providing employment to many, the next time we use an app to get eggs delivered to our doorstep we should acknowledge that a man and not a drone is delivering our goods. Next time we think of buying something on Amazon, we should remember that while digital platforms have “enabled innovation, created jobs, expanded market access for merchants and brought convenience that could not have been imagined…”, the “demand for instant gratification that they fulfil has high social and economic costs.”

At a time when apps have come to determine how we shop, commute, eat, dress, OTP Please provides a useful toolkit to understand this technological world. Vasudevan ensures that her tone is neutral and while laying out all the facts she leaves it to the reader to cast judgement. By speaking to more than 150 people over a year across five countries the author gives us a book that is both revelatory and relevant.