The Imperfect Queen

TO BE A woman in India’s mythological or historical tapestry is a changeable thing. Your identity, if indeed it is ever acknowledged at all, is subject to the vagary of every passing religious, political, and cultural wind. Complicated personalities are burnished into the smoothness of impossible goddesses. When the record-keepers are colonial men, then an additional suffocating layer of prejudice is added. And so it is that Begum Hazrat Mahal, a leader of the 1857 uprising, was called a ‘black Semiramide’ (queen of Assyria) or a ‘Penthesilea’ (Amazon queen) while Rani Laxmibai was, confusingly, both a brave ‘Amazon’ and a licentious ‘Jezebel’ (biblical troublemaker), again according to British testimonies of the time.

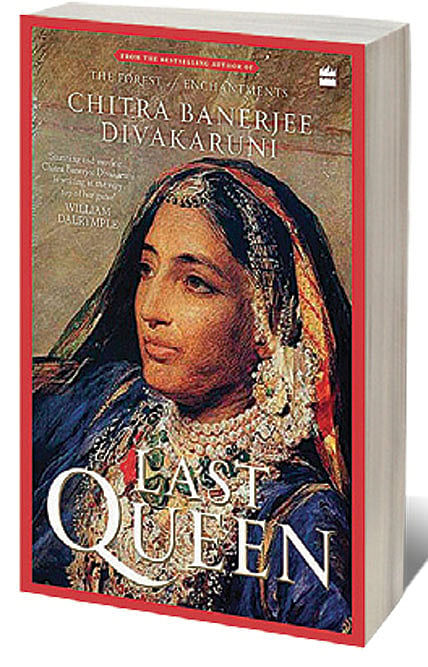

Given this backdrop it is always refreshing to see this narrative challenged, and to have an Indian-origin author write the life of a woman, as Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni has done with her latest book—a work of historical fiction on the life of Jindan Kaur, the last wife of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Indeed Divakaruni has kept the lens firmly on women characters through a long and successful career—from her short story collection Arranged Marriage, to her fiction with The Mistress of Spice, to her mythological re-imaginings with The Palace of Illusions and The Forest of Enchantments.

Ranjit Singh created a unified Sikh empire with its capital in Lahore in the 19th century but when he died in 1839, his kingdom faced the twin threats of a bloody succession struggle and the voracious ambitions of the British Empire. Jindan was only 26 when she was widowed, with a five-year old son, Dalip Singh. With virtually no powerful allies by her side, Jindan took on the dangerous task of trying to claim the throne for her young son.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

To her great credit, Divakaruni has not baulked at showing Jindan as a real human—with all her flaws uncomfortably exposed. If there has always been a tendency to venerate heroic women in India who are flawlessly perfect, then Jindan is altogether more sympathetic for being a woman who repeatedly fails. As a barely educated village girl in a volatile and simmering court, Jindan is hopelessly out of her depth. She is dangerously impulsive, vengeful, and short-sighted. She is sometimes tormented by clashing loyalties, as a mother, a sister and a lover. Despite all this we remain on Jindan’s side, sometimes against our better judgement, through a life that would be deemed extraordinary in any time and age, and which has been almost entirely forgotten in India.

Divakaruni is at her best when describing Jindan’s relationship with the world, and the people around her—the conversations are crisp and believable, and the motivations sensitively described. This facility and ease of language and pace explain why many of Divakaruni’s works have been translated to the screen—there is a visceral and immediate sense of belonging to Jindan’s world.

If the book stumbles momentarily, it is briefly in the latter half, when the action moves out of Lahore fort and into the war-scorched battlefield of northern India around 1857. This was a momentous moment in India’s history, filled with remarkable characters, as different regions rose in revolt against the British Empire. Moving at breathless speed, the narrative summarily deals with a number of famous names—Laxmibai, Tantia Tope, Mangal Pandey.

Unlike many women in Indian history, Jindan Kaur was well documented. A lot of that recording, however, was done by the British, who tried to counter her undoubted charisma by branding her ‘The Messalina of the Punjab’, after an infamously licentious Roman Empress. In The Last Queen, the story unfolds confidently in Jindan’s own language, clothed in India’s kaleidoscope colours. And so we have the story of an imperfect Indian woman in complicated times who dared to dream of glory. May this tribe of imperfect women increase.