The Gulzar-verse

“YOU MUST HAVE been a Bengali in your past life,” I exclaim on the phone. The voice at the other end, famous for its gravelly undertone replies, “You mean I am a Punjabi in this life?” Words mean various things to 87-year-old Gulzar: they are playthings to be deployed in songs asking “personal se sawal” (personal questions). They are truth bombs to be hurled at society in films like Aandhi (1975) and Maachis (1996). And they are soothing mantras, poems to live by in a soulless world: “Waqt rahta nahin kahin tik kar/ aadat is ki bhi aadmi si hai” (Time doesn’t stand still for anyone/ It behaves much like humans do).

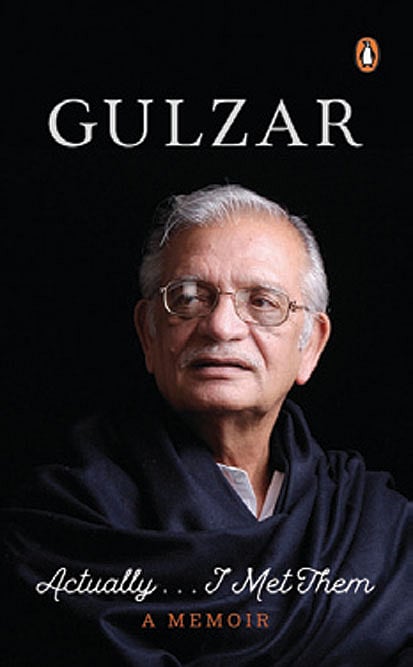

In Actually... I Met Them (Hamish Hamilton; 121 pages; ₹ 399), a memoir that examines the influence some of India’s greatest minds (many of them Bengali) have had on him, Gulzar describes various members of his “Bengali family”. “Temperamentally I enjoyed interacting with the community. It actually comes from my love for the Bengali language and my guru, Bimalda [director Bimal Roy],” he says, adding, “and before that Rabindranath Tagore, since I was in Class VIII.” Each of the 18 chapters is dedicated to an individual with whom he’s had a long and fruitful relationship such as Pandit Ravi Shankar, Sharmila Tagore, RD Burman etcetera.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The book is based on columns with Sanchari Mukherjee for a Bengali newspaper’s Sunday edition. Gulzar would speak to her in Hindi, English, Urdu and Bengali, and she would write them in Bengali. The book has been translated from Bengali to English by Maharghya Chakraborty, but the words and voice remain very much Gulzar’s.

The memoir has a galaxy of greats, from Satyajit Ray to Pandit Ravi Shankar to Mahasweta Devi. They were rooted in their culture, says Gulzar, adding that they could be seen as representatives of Indian culture. “They were exemplary Indians,” he says, “they knew their music, literature and dance. One could feel India with them, smell India with them. There are people like Shyam Benegal and Naseeruddin Shah now but perhaps because the milieu has changed, I am missing those greats who were the essence of my culture, my people, my India. That’s why they were able to best showcase India to the world, whether it was Ray in France, Ravi Shankar in England and USA or Mahasweta Devi at the Frankfurt Book Fair in Germany.”

Born Sampooran Singh Kalra in 1934, Gulzar is an extraordinary writer, poet, filmmaker and thinker, who was sent off from St Stephen’s College to Mumbai to make a living for himself. He soon did, but not what his family would have wanted. He started working as a motor mechanic to make ends meet and dabbled in translation from Bengali to Hindi in his spare time.

He inspires us, so naturally it is interesting to know who inspires him. It ranges from the mercurial singer Kishore Kumar to the eternal beauty Suchitra Sen; from the personable Bengali Mahanayak Uttam Kumar to the velvet-voiced singer Hemanta Mukhopadhyay (Hemant Kumar).

There is much to learn from the pantheon of heroes in his memoir. Bimal Roy’s commitment to work, so much so that he died with his boots on, directing Amrita Kumbher Sandhaney (1982). Kishore Kumar’s playfulness, sometimes involving disappearing into his cupboard via a secret staircase to avoid a producer. RD Burman’s love for experiments, whether it was crossbreeding chillies on the rooftop of his garage or using soda bottles for sound effects. Hemanta Kumar’s large-heartedness as he drove through the city in his Mercedes, helping those in need.

THERE IS SO much joy in the pages of Actually… I Met Them, but also so much sorrow. Gulzar speaks of Bimal Roy dying of cancer, “he seemed to have shrunk, gotten smaller, like a cushion on the sofa.” Or his relationship with Pancham (RD Burman): “Both of us had kept a part of our own selves in safe custody with the other, which ensured our views always took on similar hues. I have but one regret. That I was left behind, like some sort of an incomplete half. A large part of me departed with Pancham; the Gulzar that remains is but half-complete,” he writes.

There is the grief of having outlived some of his finest contemporaries but also the sadness of seeing an era being eroded. The memoir captures the romantic ’60s, of cigarettes and smoky rooms, orchestras and communist beliefs, endless addas and Rabindra Sangeet, cups of tea and pegs of whisky, films made for friends without payment to memorable dialogues that would be written on the morning of the shoot.

Around the mid-seventies Bombay changed and became ruthless, says Gulzar, and gentlemen filmmakers such as Hemantda moved back to Kolkata. Till then it was a gentler industry, run by Bhadralok Bengalis, who brought with them a deep love for literature, music and cinema. Money was less important for them. Hrishikesh Mukherjee would forget to shoot when playing chess with writer Rahi Masoom Raza, while Salil Chowdhury would slack off work playing carrom. As Satyajit Ray once said—which Gulzar overheard—if we can’t spend money, at least we can spend our brains.

The memoir also recalls numerous acts of kindness.

Hemantda telling young Gulzar not to forgo his Gulzarish universe. Bimal Roy sending him to Delhi by plane so he could attend his sister’s wedding. Actor Abhi Bhattacharya providing his home as an adda for hungry Bengalis.

As he writes: “Those days the Bengalis of Bombay were guaranteed to be found in one of two places. The first was a place of work—Bimal Roy Productions. This was because Bimalda was an affluent producer who would nourish and sustain people, me included. I was a converted Bengali as it was. The second was Abhida [Abhi Bhattacharya]’s place, where everyone would gather to relax. Being a new Bengali, wherever I used to find my kin, I would usually insert myself there.”

There is also much of what makes an artist; a snatch of quirkiness like Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s tea-drinking pet dog, Suchitra Sen’s grape-eating crows, and Kishore Kumar shaving his head bald just before the shoot of Anand, 1971 (where he was cast as the lead, and which caused Rajesh Khanna to be hired instead).

There is the making of the song ‘Musafir hoon yaaron’ (Parichay, 1972). It was written over a four-hour drive through nocturnal Bombay with just the car’s cassette recorder for accompaniment as Pancham drove and Gulzar wrote. There is Sharmila Tagore stepping in with one day to spare, replacing Rekha in Namkeen (1982). There is Bhimsen Joshi working as a cook in actor Pahari Sanyal’s home in Kolkata. There is Mahasweta Devi declaring she is a Dilip Kumar fan. There is Ritwik Ghatak landing up at Bimalda’s home, wild hair matching his wild ways. There is Sanjeev Kumar, facing his death head-on. There is Bimalda and his countless ways of saying “Hmm”. As Gulzar says, “One hmmm had a hundred versions and could say a hundred things. If today I have to say there was someone cooler than MS Dhoni then it is Bimalda. He was also a captain/commander in his own way.” And there is Pandit Ravi Shankar composing the music for Meera (1979), as Gulzar chases him from New York to London to Amsterdam.

As for Kishore Kumar, Gulzar says, “Poochiye mat (Don’t ask). This was a man who was alive every inch and every moment. I never saw him dull or sad. He had a big portrait of KL Saigal in his room and once in the evening he had five or six TV sets with him on all of the screens at once. And he turned and said to me: ‘See there is not one Kishore but many.’ He was not scared of anyone in authority. Even while singing, expert artists like Lata Mangeshkar wouldn’t know whether to laugh or cry. He would sing his line and move out of the recording glass cabin, play pranks on the orchestra, then on his cue he would be back and sing his line. It was superb.”

There is Suchitra Sen, with the whole unit calling her Sir, and a lifelong friendship developing on the sets of Aandhi between Sanjeev Kumar, Sen and Gulzar.“Whenever I would go to Kolkata it was courtesy to inform her. She would invite me over to have tea. Her granddaughters, Riya and Raima, were little girls then. They would come to Mumbai and narrate stories about her, about how they couldn’t wear this or that in front of her. And I would ask, ‘Darte ho kya (are you scared)?’ And they would say, ‘Yes, unse hamari maa bhi darti hai (even our mother is scared of her).’”

There is mention of his most beloved Bengali, as well, his wife, actress Raakhee, whom he met in his spiritual home, Kolkata.

Yet the greatest star among these talented people is Gulzar. He is the wordsmith, the visionary, the fabulist. The man who can craft words out of his imagination and create images from another world. Who could, as Pancham famously asked him to, compose music for the morning newspaper. Often outrageous, always adventurous, Gulzar remains a man of words and the heart on and off the page.