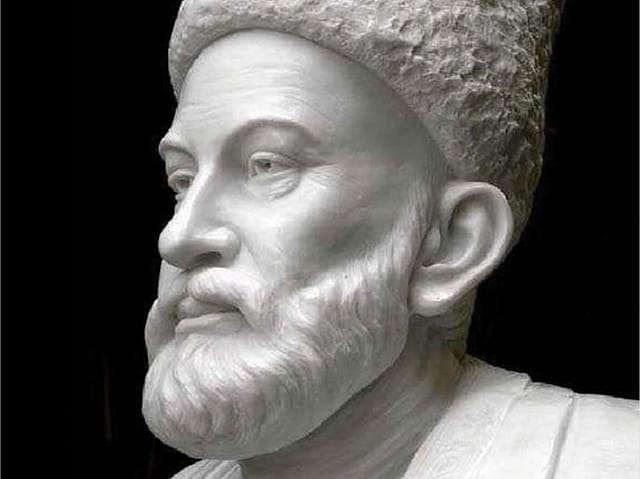

The Garden of Ghalib

EVEN THE BEST among us colour outside the lines once in a while; unprecedented problems call for unconventional solutions, after all. Mirza Ghalib (born Mirza Asadullah Khan Baig), widely regarded as the greatest Urdu poet of all time (though his Persian corpus is much more voluminous), understood this well, as does Mehr Afshan Farooqi's Ghalib: A Wilderness at My Doorstep, A Critical Biography (Allen Lane; 416 pages; Rs 799), a new biography of the 19th century poet. In the first chapter itself, Farooqi tells us that the great man may have invented a Persian tutor for himself, an Iranian scholar supposedly called Hurmuzd, better known as Abdus Samad. Why did Ghalib feel the need to make Hurmuzd up, that too when he was well into his sixties, having never previously mentioned him? Or was there indeed a Hurmuzd and Ghalib had, for whatever reason, kept quiet about him for decades?

The answers, as this thorough and wide-ranging scholarly work shows us, are seldom straightforward when it comes to Ghalib. After an abundance of early work in Urdu, the poet made a conscious shift to compose exclusively in Persian. One reason was that Ghalib desperately wished to be seen as a master poet working in a classical language. Another reason, as Farooqi explains was the poet's long-running feud with Indian Persian writers who, in his opinion, could never match the accuracy, range and idiomatic excellence of the Iranian masters. These strong views culminated in a rancorous mushaira in Calcutta, at the end of which Ghalib almost came to blows with those who resented his views on Indo-Persian writing.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

But over and above these relatively straightforward motives is a much more subtle prong: Ghalib's ancestors belonged to Samarkand; besides, as Farooqi says, 'Before the modern modes of conceptualising belonging came into being, it was not uncommon to have transregional sensibilities of identity. The distinction between the native and the foreign was a creation of the colonial state that wanted to pin down the former as a category to be dominated.' Ghalib thus claimed Persian for himself via his Samarkand ancestors, an act not just of transregionality but also of establishing 'deep historical-cultural roots'.

Farooqi's Ghalib is one among several Indian works either about or involving Mirza Ghalib. Towards the end of 2019, Raza Mir had published a biography of the poet, Ghalib: A Thousand Desires (Penguin; 200 pages; Rs 399). Earlier this year, Mir also published Murder at the Mushaira (Aleph; 360 pages; Rs 799), a novel set in the Delhi of 1857 with Ghalib playing detective. In Rabisankar Bal's Bangla novel Dozakhnama: Conversation in Hell (translated into English by Arunava Sinha, published in 2012), Ghalib and Manto enthral the reader with a long conversation beyond the grave. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi (who passed away in December 2020) began his 2014 collection The Sun That Rose from the Earth with a 75-page novella called Bright Star, Lone Splendour, in which the narrator, a young Rajput poet called Beni Madho 'Ruswa' travels to Delhi in the aftermath of the 1857 battle for Indian independence (to the neighbourhood of Ballimaran, where Ghalib lived), to meet Ghalib and get him to sign copies of his divan or collection of poems.

It's fair to say, therefore, that Ghalib's appeal is hardly restricted to those familiar with the rhythms of Urdu. In fact, for a lay readership, Ghalib has become a metonym for the flamboyance, romance and sophistication associated with Urdu poetry.

Most author biographies choose one of the two—they focus either on the texts produced, or the life lived. Almost every biography has elements of both, of course, but by the end of chapter two or three, you know which 'mode' will dominate the narrative. Farooqi, to her credit, refuses to settle for one or the other. Her Ghalib provides a wealth of close readings for the experienced Ghalib devotee, including analyses of some Persian texts that have never been translated into English. But to the lay reader's delight, it is also dogged in its pursuit of the hard facts of Ghalib's life, in a fairly accessible journalistic way.

Why did Ghalib reject a large number of his early Urdu verses? Was it just another symptom of his shift towards Persian or was he resentful of critics who (according to him) reserved their praises only for the simplest, most easy-to-follow verses (as Farooqi points out, many of Ghalib's most enduringly popular verses were actually a part of this youthful 'fresh style' or taza-goshi, followed by earlier poets like Abdul-Qadir Bedil)? Farooqi seeks to answer questions like these. And there's a fair bit of range on display, too, thanks to Ghalib's eventful life: one chapter following the arduous journey Ghalib made to Calcutta (the seat of the British administration) in 1827 reads like a roadtrip thriller (indeed, it could be argued that any 19th century journey upwards of a thousand km was risky by default).

'When we think of the challenges of a nearly 3,000-kilometre journey that was interrupted by long episodes of illness (five months spent recovering in Lucknow, six in Banda and one in Banaras), we have to admire Ghalib's tenacity of purpose.' Along the way, Ghalib was deeply moved by the beauty and quiet splendour of Banaras. He would compose his famous masnavi (a Persian form comprising couplets with the aa/bb/cc rhyme scheme) Chiragh-e-Dair (Lamp of the Temple) as an elaborate tribute to the city that so captivated him.

Other entertaining sections include a round-up of a massive, years-long feud Ghalib cultivated with Indo-Persian lexicographers. Basically, Ghalib was no fan of Burhan-e-Qati (The Cutting Argument), the 17th century Persian dictionary compiled by Muhammad Husain Tabrizi. He wrote a book-length critique called, cheekily, Qati-e-Burhan ('The Cutter of the Argument' or 'He Who Cuts the Argument'). He was once asked by educationist and philosopher Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan to write a preface to the latter's new edition of A'in-e-Akbari. A derisive Ghalib instead composed a poem in Persian making fun of the project and also urged Khan to 'move with the times'. Despite this slight (good-natured or otherwise), it was Sir Sayyid who later successfully lobbied the British for the clearance of Ghalib's pension dues, Rs 2,250 in arrears (by no means a small amount circa 1860; worth about Rs 7 lakh now). Then there's the time Ghalib wrote a qasidah (a poem written in praise) for Queen Victoria, which was promptly returned 'as an item of mere flattery'.

All of this unscripted drama is the stuff of Netflix gold: no wonder that the fascination with Ghalib has often spilt over into fiction.

RAZA MIR'S BIOGRAPHICAL Ghalib: A Thousand Desires begins with a section called 'Four Imagined Vignettes from Ghalib'. The first of these vignettes imagines Ghalib at the end of his 1827 trip to Calcutta, at Howrah's doorstep. He has just written his legendary Chiragh-e-Dair a few days ago and now, he awaits the arrival of a new poem, this time in Urdu. These are beautifully written little passages, and they show not just the breadth of Mir's research but also the genuine affection he has for his subject, tempered with playful scepticism.

'This journey insistently calls an Urdu muse forth, one that invites him to shake off the abstruse and metaphysical and indulge in the spare parsimony of feelings. He glances at the lines he has written that very afternoon:

Kalkatte ka jo zikr kiya tu ne hum-nasheen

Ek teer mere seene pe mara, ke hai

When you mentioned Calcutta, sweetheart

Oh you pierced my chest with a dart!

He determines not to finish that poem until he returns to Delhi. There will be time to reflect on the pleasures of Calcutta with the benefit of experience, rather than the imprecision of anticipated pleasure.'

Other representations, like Shamsur Rahman Faruqi's Bright Star, Lone Splendour, paint the picture of a complicated, brilliant man who was by no means immune to jealousy, flattery and even prejudice, after a fashion, especially when it came to the question of Indo-Persian writing. This novella's narrator Beni Madho 'Ruswa' is rather taken with the great man—this is intended, among other things, as a stand-in for Ghalib's first biographer and last student, Altaf Hussain Hali (1837-1914). Hali's biography is an extremely valuable resource, as Farooqi keeps reminding us in her Ghalib; the man knew Ghalib in person, after all, which is gold for academics. And yet, Hali keeps mixing up dates and at several places, fails to scrutinise his subject at all—the subject of Hurmuzd, Ghalib's alleged Iranian tutor, for example, receives only a regurgitated as-told-to with zero follow-up queries.

In Bright Star, Lone Splendour, therefore, Farooqi smartly outsources the 'critical thinking' part of the endeavour to the fictional Ghalib's utterances. Through these lines, the reader is forced to evaluate Ghalib on their own terms and not through the rosetinted glasses of Beni Madho 'Ruswa'. Here, for example, is Ghalib ranting about Indian exponents of Persian grammar and poetry, while in the same breath extolling his own superiority:

'Look, my boy. The subtle points and mysteries of the Persian language are implanted and imprinted in my soul, just like the natural grain or streak in steel, or the moisture of the morning breeze in the delicate veins of a flower. As against me, where are those lowly lexicographers and grammarians like Mullah Ghiasuddin of Rampur or Diwali Singh Qateel, a Khatri of Faridabad! Even their remotest ancestors wouldn't have had a glimpse of Iranian soil!'

In this context, Mir's Murder at the Mushaira deserves mention. Here, an aggrieved character called Ishrat (Ghalib once slapped her husband after the latter dared to steady him as he was falling down the stairs in a drunken stupor) tears into Ghalib's scholarship, or lack thereof, in a hilarious, tongue-in-cheek passage: 'He is the worst poet in the world. Even I can write poetry by rhyming aaftab and shabaab and sharaab and janaab, the doggerel-monger.'

To an extent, the character flaws these fictional representations hint at are fairly standard writerly vices, like a certain kind of pride that spills over into braggadocio, as these passages show. Towards the end of Ghalib, therefore, Farooqi focuses on all the non-writerly ways in which Ghalib was ahead of his contemporaries. For example, he grasped the value and the far-reaching consequences of the printed medium far more quickly than any other Urdu writer of his time. As Farooqi points out, he was an internationalist before we even had a conception of such a thing in Indian literature. He saw a world of readers unencumbered by linguistic or national boundaries—and print was the perfect conduit to reach out to this brave new world.

As the man himself wrote in a ghazal that didn't eventually make it to his finished divan (Farooqi closes her book with these lines, too):

'I sing from the warmth of the joy of imagination,

I am the bulbul of a garden yet to be created.'