The Dalit Who Got Out

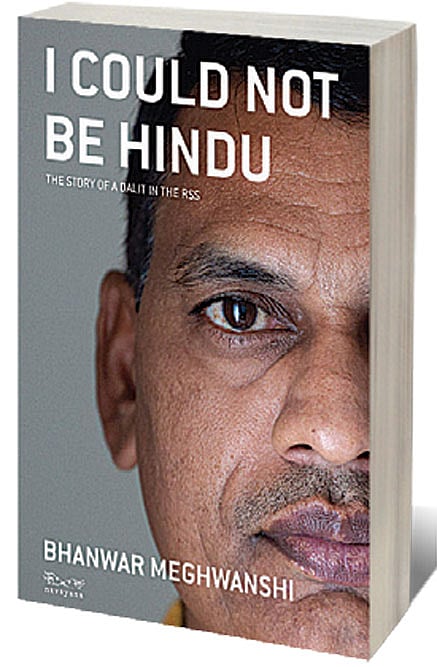

BHANWAR MEGHWANSHI spent five years in the RSS. Since then, he has spent more than two decades fighting against everything it represents. His memoir, I Could Not Be Hindu: The Story of a Dalit in the RSS, translated from the Hindi by Nivedita Menon, (Navayana; 240 pages; Rs 399), is a fascinating tell-all of a bitter break-up: between a loyal foot soldier and the world’s biggest Hindu organisation.

The tightly packed, candid exploration unravels in four acts: Meghwanshi’s romance with the Hindu right, his growing fervour, his eventual disillusionment and its aftermath. The narrative heft turns on this: the organisation that preaches brotherhood between Hindus, turns out in practice to be discriminatory against some Hindus.

The manuscript circulated among publishers for five years before it was published by Navarun last October in Hindi and by Navayana early this year in English. Meghwanshi had told parts of this story before, in articles, online and in public, but this was the first time he was telling it in its entirety. “Some publishers did not want to take a risk. Some said it should be edited, the words should be changed,” says the Jaipur-based activist and social worker, in Hindi. “I said I’m not writing fiction, this is my story, how can I change it?”

The RSS was set up in 1925, by KB Hedgewar, a doctor from Nagpur, with the intention of strengthening Hindu society and promoting the idea of a Hindu nation. Initially inspired by right-wing European groups like the Nazis, the RSS, premised on a model of local branches or ‘shakhas’, is now a sprawling social outfit that also runs schools and welfare programmes.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

As a boy, in Sirdiyas village in Rajasthan’s Bhilwara district, Meghwanshi, like many young men, fell under its spell. At first, the pull was visceral. “At 13 you are not able to understand ideology. You just know that you like to play,” he says. “Their shakhas have exercises and songs. The attraction was physical activities.” Only about five months after joining did Meghwanshi realise he had been attending a shakha. The daily routine gradually morphed into something more sinister, as a steady drip feed of ideological rhetoric—broadsides against non-Hindus, exhortations to nationalism—seeped into the recruits’ minds. Meghwanshi had never in his childhood seen or known a Muslim. Now the RSS worthies were telling him they were scoundrels and traitors. He was hooked.

“You are taught you are from the best religion, your blood is Aryan. When you start thinking you are the best then there is no need to teach the other is lesser than you,” he says, enlisting the myriad attractions. “Their target group is young children... Dalit and Adivasi youth, used to insults, at a young age in the RSS we get a lot of respect, they call us bhaisaheb… Then the talk of nationalism…. At this age, you want to do something for your society, your country. They exploit these feelings. Then it gets more hard line. You don’t realise when it deepens. It doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a process.”

Meghwanshi’s book is a clear-eyed reckoning of his personal journey, but also offers insights into the organisational activities of the RSS, and the miniature scale at which their influence operates. Though the exploration of Hindu nationalism, or the Ram Mandir movement is not new, what we see here is the insidious way propaganda works in the minutiae of the everyday.

Despite clashing with his family, in 1990 15-year-old Meghwanshi was among the kar sevaks who travelled to UP with the intention of destroying the Babri Masjid. Getting arrested on that failed mission dimmed his ardour somewhat. Gradually thereafter, he began to ask questions, and matters eventually came to a head in May 1991, with a single incident that exposed the casteism at the beating heart of the Sangh.

When upper-caste RSS functionaries refused to eat in his home and later threw away the food he offered them, years of Hindu nationalist conditioning vaporised in the face of obvious discrimination. “This incident was a turning point,” he says. “But even before that, I had started asking questions… [Without this incident] perhaps I would not have left, perhaps the questions would keep increasing... The way I turned and turned hard against them, possibly I wouldn’t have done that if not for the one incident.”

Meghwanshi started by writing to higher authorities, appealing to the people he knew to appraise them of the treatment he’d suffered. It didn’t work. “Honestly speaking, I wasn’t working for badlav [change], but badla [revenge], it was an individual goal,” he says, on his early years attacking the RSS in public.

But over time, that rage became the lubrication for his activism and social work, and for what he considered as his role: publicly denouncing the organisation of his youth. “Absolutely. The bitter experiences I had, and the hypocrisy I have seen, I want others to know about. Now the danger to our democracy from this ideology is increasing…I think it’s time to fight for our country and people and constitution.”

He agrees that like most of India, Dalits were seduced by Modi’s image and promise of hope, and an overwhelming proportion abandoned the Congress and voted for the BJP. But, he suspects that is now souring.

Meghwanshi is not the only disillusioned former Dalit functionary—he mentions interactions with others in his book—but he is among the more vocal. “People are told this is a very big organisation, then how can you fight it? Some people have told me, why challenge them, why oppose them, they can do anything.”

In the immediate aftermath of the rupture, Meghwashi would have arguments with former colleagues, there were sporadic threats, and one incident of misbehaviour, he says. But despite concern from well-wishers, and the pusillanimity of some publishers, Meghwanshi was never afraid of writing it all down. “If we are saying what we want to, the risk you need to take, you should take. I wrote freely, and I continue to live in the same place. I have never felt that fear.”

In fact, the opposite seems to have happened: there has been no backlash against the book. “The RSS, BJP and Hindu groups are completely silent, strategically silent. They have decided they will not speak on this at all,” he says. “The troll army is quiet. If they speak on it people’s attention will be directed to it, and they don’t want that.”

Meghwanshi doesn’t call himself Hindu anymore. When the Ayodhya verdict came out last year, the former kar sevak who had once fantasised about building a temple there, felt no joy, and little surprise. “But I was a bit disappointed that [the Supreme Court] didn’t consider logic,” he says. “[They] ruled on the basis of feelings.”

After leaving the RSS and denouncing Hinduism, Meghwanshi briefly flirted with the idea of conversion; and adopted Christianity. Eventually, he dropped that too, and now has little patience with religion, though he appreciates the cultural aspects including devotional songs across faiths, and has fought alongside Dalits denied temple entry.

“In every religion there is caste in some way or the other. So what difference can converting make?” he asks “Not liberation through religion but liberation from religion is my personal belief. But if someone is religious that’s up to them. I don’t have a problem with that.”

As religious polarisation deepens, Meghwanshi warns, “Rationalists have been attacked, now we are seeing people don’t just make threats but are shooting in places like Jamia. Now the danger our democracy is facing, it’s very great.”

He concedes that fissures have always undergirded the social fabric, and India has never been perfectly harmonious. “The dangers never emerged this seriously,” he says. “This ideology was there before but they were not in government. Now they are in government… Now they believe we can do anything and nothing will happen to us. We can rape, we can shoot in Jamia, the administration and media will help us. When those in power support such thoughts and deeds openly then the danger is in its most naked form.” There are moments when he cringes thinking of his association with the RSS.

Meghwanshi isn’t despairing entirely though. He sees in the people’s movements, the opposition to CAA and NRC a repudiation of everything RSS. “In every city people are going out with the constitution and flag, the way they are standing together, that is the only response,” he says. “We are also seeing people’s power. If we unite on big issues, I think they can be defeated, I am hopeful.”

Meghwanshi, who has also worked as a journalist, hopes to write more. “There are many things left to say,” he says. “This is just the beginning.”