The Aura of Absence

Empty streets and hollow hearts. Looming pillars and dark, shadowed souls. Vacant spaces and abandoned people. An extraordinary pathogen in the air unleashed a shameful illness—of wilful ignorance and careful incomprehension. As those who could hunkered down in their homes during the sudden and unprecedented lockdown necessitated by Covid-19, the men and women who build our houses, serve us daily and keep our cities aloft came out of the crevices and hideaways that are airbrushed in usual picturesque urban portraits. Some marched home, their belongings and memories carried on and in their heads, their children barefoot, hungry and uncomprehending. Others were worse off. With no villages to go back to, they remained in their makeshift homes, under flyovers, near railway tracks and sometimes, and most poignantly, like a six-month-old baby, wrapped in a sheet, abandoned in graveyards.

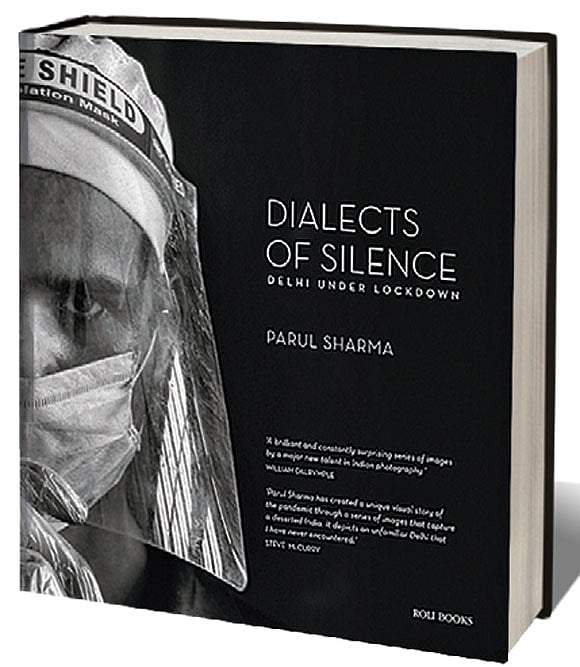

But there were some who were turning their gaze towards them, talking to them, photographing them, chronicling them, often at great personal risk. Such as fine arts photographer Parul Sharma. Armed with courage, empathy and an iPhone 11 Pro and a Huawei P30 Pro, she cut through the deserted roads of Delhi, at once familiar and strange, bereft of traffic, of officegoers, of citizens.

Lost: The Unstoppable Decline of Congress

05 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 50

Serial defeats | Leadership in denial | Power struggles

Through the urban wasteland, she photographed Delhi’s stately buildings, its forgotten homeless and its helpless animals. What has emerged in Dialects of Silence: Delhi under Lockdown (Roli Books; 156 pages; Rs 2,995) is a book that forces us to examine our own souls. Where were we when devastation was sweeping our beloved city? Where were we when fearless doctors were powered by their Hippocrates oath and Talat Mahmood songs to serve 18-hour shifts seven days a week? Where were we when bodies were being despatched to electric crematoriums and burial grounds?

We were elsewhere but Sharma was reclaiming the city space, one frame at a time. The relationship women have with cities is a curious mix of wonder and terror. Devoid of the anonymity of crowds, the city can be a threatening expanse. But for Sharma it was a mission she had set out on. The images drew her in, and her eye could not unsee. And we cannot unsee the young woman in a burkha reading the Al-Ftiah for her dead husband in the middle of the burial ground. We cannot see the befuddlement in the arch of the homeless man’s body as he talks to himself in a deserted Connaught Place. We cannot see the agony in the mother’s face as her baby clings to her breast and she dreams of her home in Unnao.

There is no languor here, only despair and urgency. In Mirza Ghalib’s deserted camp and Mir Taqi Mir’s ujada dayaar (place laid completely to waste), there is movement—that of armies of migrant labourers moving inexorably home, ambulance vans rushing towards hospitals, bodies transiting towards another world. Sharma talks of lives paused, lives lost and lives regained, and what she does well is also to place the city in its historical context, which as Jawaharlal Nehru had said has been the grave of many empires and the nursery of a republic. Here the crows look like vultures, circling Janpath, and the kneeling monkeys like tiny, meditating men. The resilience of the city ravaged so many times by so many rulers, surprised Sharma, as did the spirit of its people.

“Whether it was the gurudwaras that served food or the people who came forward to do the last rites for strangers, it was so inspiring to see people overcome the stigma of the virus. In spite of the odds, humanity won,” she says.

Sharma grew up in what was called Baird Road, near Gole Market, and knows the city intimately. She captures its staples: Partap Florist in Janpath; Loke Nath, the city’s oldest drapery store; Indraprastha College, her mother’s alma mater and Delhi’s oldest

women’s college.

Like the best work, Dialects of Silence is a personal history and a public document, of what the human spirit could achieve when the world came unstuck. And how one brave act can inspire so many others—from the police officials who waived her through barriers, to doctors who shared their new sanitised workspaces, to migrants who told their stories. Sharma did fear contracting the virus, but an even bigger fear was this: that she would miss the perfect frame. After all, she drove over 6,000km for four months in search of it.