The Art of Loss

IT’S NOT BY accident that Dominic Ullis, the protagonist in Low, is wrongly addressed as Ulysses on the very first page of the novel by a fellow passenger on his flight to Bombay. Ullis’ sojourn in Bombay does indeed resemble the journey of heartsick Leopold Bloom, from the more famous Ulysses, through a single day and night in Dublin. It also reminds us of the rhythmic wailing of Bob Dylan in Love Sick (‘I’m walkin’/ through streets that are dead / I’m walkin’/ with you in my head’). The figure of a lonely, grieving man, urgently adrift in strange and dark places, is not an unfamiliar sight in the annals of modern literature.

Ullis, a poet in his mid-forties, is going through a fallow period. His wife Aki, younger than him by around 20 years, has taken her own life in their apartment in Delhi. Devastated by grief and unwilling to face Aki’s residual presence at home, the poet flees to Bombay, the only city he knows well, and plunges back for two nights and a day, the duration of his trip, into a drug habit that had consumed his youth and which he had abandoned for the love of Aki. Each of the novel’s 14 chapters holds an important revelation about Aki, Ullis or the relationship between them. While Ullis struggles to cope with his loss, we are steered through many nooks and corners of Bombay, where the denizens of that city, rich and poor alike, are ‘doing their sport’. In the background we hear the throbbing hum of the wider world, stalking the characters through television sets and mobile phones, and laid low by the impending doom of climate change and the ugly, psychopathic liars who have captured the seats of power.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The novel’s portrait of Aki as a young, vulnerable woman in the present day is vivid and not unfamiliar. As a young child, she feels abandoned after her parents’ separation. Growing up in a relative’s house, she finds promise and takes solace in Wonderful Life, a pop song, only to discover later that the singer was in fact being ironic and bitter. As a young woman, she is alive to the looming devastation of climate change and firm in her conviction that she and her husband, along with the rest of the world, have only 12 years left to live. She is subdued and passive in her love, does not want children of her own and is suicidal underneath it all (‘Ever since I was little, I’ve wanted to die.’). She is a citizen of the country of the low.

If he asked her where she’d been, she would say, ‘I’ve been low.’ As if it were a republic to which she had a multiple-entry twenty-year visa... Once he had suggested that they take a weekend trip out of Delhi and she’d said, ‘I can’t do it tomorrow.

I’m going to the low.’ As if her low country lay everywhere, like a vast spiritual archipelago.

Ullis is shown as tentative in spirit, as befits a man recovering from long years of drug addiction, and sharply observant, a poet of dormant ambition. He is, of course, fascinated and fazed by the buried tumult in his young wife and laid to waste by her loss. Seeking a return to a familiar self in a familiar city, he trundles through his brief journey with a nonchalant (or resigned) air: ‘I don’t see why not.’ Unlike Aki, he is backed by supportive parents in a distant city, but not necessarily to good effect. When he is exhorted by his mother to hold himself together and ‘show the world what you are made of’, he replies without missing a beat, ‘I am made of clay, in particular my feet and heart.’

The narrative of their relationship is a series of conversations both in the past and present, where Aki is memory and dream, a spectral companion resident in Ullis’ head. She is also present in the box of ashes that is Ullis’ sole burden, waiting to be let go in fast water. What we learn (yet again!) from these conversations between the couple, both real and not, is that even in love, we are alone in our own low countries, weighed down by ‘anxiety and damage’, and it’s love that must help us ‘keep each other alive’. When Ullis falls into the drug-addled abyss of his past to cope with the shock of Aki’s sudden departure, it’s the memory of his exchanges with her that restores him in the end to the living world. Thayil’s accounts of these conversations are insightful, moving and poignant: Communication loves concealment. Speech leaves the mouth with a set of known concealments. It falls upon the ear with a set of unknown ones.

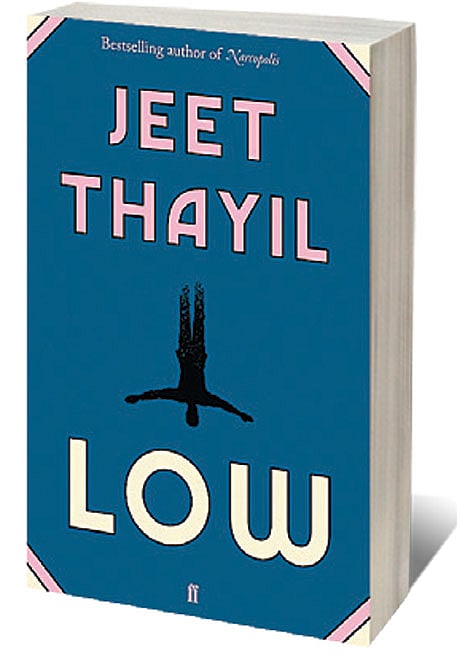

Low is Thayil’s third novel, after Narcopolis (2012) and The Book of Chocolate Saints (2017). As in the first two works, the author’s intimate knowledge of Bombay—certain parts of it, at any rate—is on full display here. Ullis’ sojourn includes a drug party with young professionals in Bandra, poolside drinks with a hotelier’s heiress at the iconic Taj Mahal Hotel, a dinner party at noon with gangsters somewhere near Walkeshwar, a sit-down dinner in a mansion in Alibag, late night drinking (and snorting) with a politician inside a shady dance bar in Tardeo, chasing heroin from silver foil at sunrise on an anonymous pavement in South Bombay in the company of a homeless lad called Sonu, followed by breakfast in an empty restaurant in Bandra, before he leaves for the airport for his return trip. Bombay has been done and done, in fiction and non-fiction, in memoirs and films. In this novel as elsewhere, it always feels like there will never be an end to writing about Bombay.

The repertoire of intoxicants ingested on this weekend trip includes: a ‘bag’ of low-grade Chinese powder, fondly called meow, a bottle of Jim Beam, two packets of cocaine and a gram of h-dash-in, a Nigerian drug dealer’s ludicrous code-word for heroin.

A poet through most of his career who turned to writing fiction only a decade ago, Thayil writes with a relish for the language and excels in descriptive prose. Whether it is contemplation of the waterscape during a taxi ride on the Sea Link, or a glimpse of the barricaded Gateway of India from a suite high up in the Taj, or the boat journey from Alibag to the city (‘he looked up at the sky, alert for augury and fray’), the text is never less than absorbing.

A set-piece describing a visit by the couple to Aki’s 70-year-old father’s home in a distant tree-shaded suburb, preceded by prayers at a Hanuman temple in the neighbourhood (‘...the front pillars covered with brass bells, the uvulas slack like knotted tongues’), is worth a particular mention. Ullis’ unfailing eye for the absurd, in himself as well as those around him, leavens the narrative with thick dollops of black humour, especially in the Bombay scenes.

The novel is the story of a couple laid low from within and without by their own pasts and the trajectory of the world in which they live. It’s an exploration of grief and the possibility of redemption under these conditions. Low ends with Ullis striking an optimistic note when he recalls what Aki had once told him, ‘He who saves one life saves the world entire.’ Well, sunny or not, it’s at least a reason to love again, and that ought to be enough for now.