The Act of Remembering

PRISONER 218 D, inside one of the 693 jail cells in Port Blair, is thinking of a word. She is thinking of a word because in that starfish- shaped jail on the Andaman Islands, despair runs like a confused chicken, unable to stop, unable to anchor itself to any one thing. Prisoner 218 D is thinking of her father’s favourite word: rimjhim. Pakistani author Uzma Aslam Khan (best known for her book Thinner Than Skin) writes, ‘He would listen to the gentle rhythm of raindrops outside his bedroom window, tapping his right forefinger on his left knee, and ask how a single world could mirror the cadence of a single occasion so precisely.’

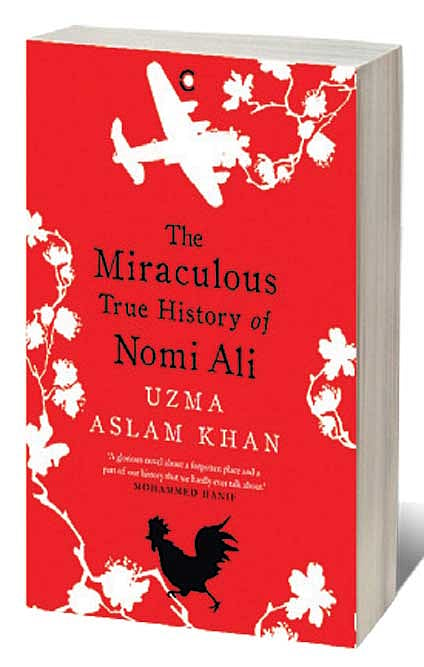

As I read The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, this beautiful monster of a book, I tried to imagine if there could be one single word to mirror the cadence of Khan’s writing, a writing that feels as familiar as old prayer beads, its lyricism only emboldened by its repetitiveness. Or maybe a word to mirror the experience of being pulled into this frightening island, this ‘paradise’ for convicts of British India, where prisoners become settlers and children become the Local Borns, where freedom is not so much about being free as is it about being unfree.

Into this world, of World War II, of the Indian freedom movement, of the British and the Japanese exchanging bombs, of injustices being shipped to the Andamans and then conveniently forgotten, Khan situates her story of Nomi and her family, of Aye, and of Prisoner 218 D. I devoured these small, simple lives meeting terrifying odds, flitting between todays and tomorrows so easily in Khan’s prose, just as the island itself seemed to be devouring them.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The book begins with the SS Noor ship and a new load of prisoners arriving to the island and the local crowd gathering, including the children Nomi, her brother Zee, and their best friend, Aye. They watch Prisoner 218 D (‘D’ for dangerous, Zee tells Nomi), shackled to another prisoner, making her way up to the jail. There is a moment when Prisoner 218 D locks eyes with both Nomi and Aye (Aye, the boy who will save her, and Nomi, the girl she will save). This moment somehow becomes the springboard for a cataclysmic set of events, as if fate could not forever remain chained to human whims.

And when it begins, eventually claiming Zee’s life, it changes Nomi irrevocably (she is only 13), plunges her mother into depression and her father who arrived on the island as a prisoner drowns even more into his endless puddle of regret. And just like how a seemingly unconnected moment of seeing and being seen can be profound, so to one death in an island of frequent deaths and torture, becomes a thread that resonates.

Khan paints her characters with a loving, generous hand, almost as if making up for the lack of hope and giving us small, powerfully self-contained moments—Nomi comparing Aye’s feet to Christ; Zee obsessing over his English essay; Nomi’s father praying; the Japanese doctor Mori and his ukiyo-e prints and his tea; and of fireflies, ‘the pathways through shadow to light’. Their life unfolds and spreads like mushrooms in a forest, urging you to remember, and urging you to find delight in the remembering.

So maybe this is the word I am looking for—remember—because, as Prisoner 218 D shows us with rimjhim, it is in the act of remembering that history is perpetually defined, and defied.