Spot the Killer

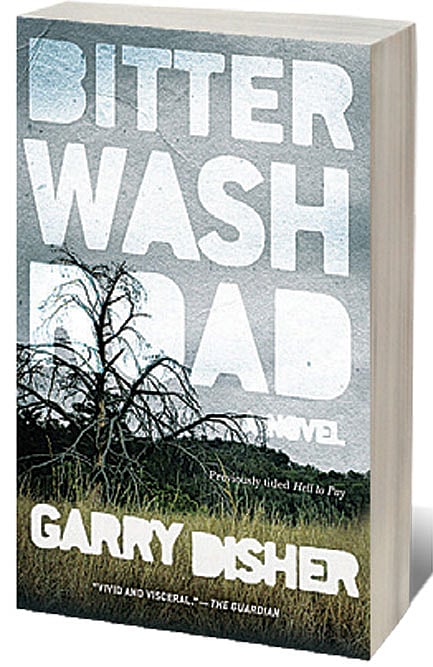

TOLSTOY SAID, ALL stories fall into one of two categories: A person goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town. Garry Disher’s story fits into ‘a stranger comes to town’ trope. He skilfully evokes the loneliness of the outback for a stranger who has to fit himself into a tight-knit community and gain their trust without getting too close and compromising his ability to investigate. Constable Hirsch has been turfed to a small backwater town for tattling on corruption among his former colleagues. His new colleagues hate him, and Internal Affairs is still sniffing around trying to frame him. He thinks his new colleagues are out to get him when a bullet flies past his head in the outback. Two children are practicing shooting the bad men. The gun belongs to the boy’s father, a prominent landowner fallen on hard days but pretending that all is well. His wife is found dead with a shotgun between her knees in a tin shed she hated. The constable thinks it is murder, but the father is a good friend of his boss. Add to this, the body of a teenage girl found in the bush, accusations of police brutality, whispers of sexual favours demanded by powerful men of the community from underage girls, a commissioner who wants you to inform on your new colleagues—you have a terrific plot with deep conflicts. As the main character asks—do you stand by and let rapists and corrupt policemen carry on or do you do something about it?

THIS IS A man-comes-back-to-town story in a layered narrative that surprises and satisfies. The story is told in transcripts of recorded conversations of an unreliable narrator on a phone. It begins with a police inspector sending a letter to a Professor Mansfield saying they have recovered 200 deleted audio files from an i-Phone belonging to a missing ex-convict Steven Smith, and want his help to understand and decode it. Forty years ago, Smith found a copy of a children’s book by disgraced author Edith Twyford. For the Enid Blyton and Five Find-Outers fans out there, Janice Hallett’s Twyford is a loosely disguised version of the author whose books, in real life, faced charges of racism and sexism. The margins of Twyford’s book contained strange notations and markings, and when Smith took it to his English teacher, Miss Iles, she is convinced the notations are secret code to a puzzle from the dark days of the Second World War. When he gets out of prison and his respectable son from a long-ago girlfriend rebuffs his attempts to connect, Smith decides to find out what happened to Miss Iles who disappeared after a school trip with Smith and four classmates. Smith has no memory of what happened on the trip and how they got back home. He dictates into his son’s old i-Phone, a diary of an investigation into the Twyford Code. Braided in is another story of how Smith landed in prison. As he revisits the people including his four classmates and places of his childhood, he finds out that Miss Iles thought the disgraced Edith Twyford had hidden clues in a secret code and cracking it would lead to a treasure. With the help of a librarian, Lucy, Steven makes headway into solving Miss Iles’s disappearance, but it becomes clear from the audio files that he is in danger from others who too are bent on solving the code.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Hallett does a fantastic job of deepening the emotional landscape as we peel off layer upon layer of the mystery. The twist at the end was as unexpected as it was satisfying. Her achievement is all the more remarkable given that the story is told in transcripts of audio files. Her first book, The Appeal written in a similar vein using emails and documents, was a bestseller, but this one is far better. Its emotional heart is firmly tethered to the missing Steven Smith’s aim to be a better father and to right the wrongs of past choices. “I’ve done plenty I’m not proud of,” he says in Audio File 10, and this is his chance at redemption. Hallett delivers a brilliant concept, skilful narrative and a satisfying read with panache.

SET IN 1920S Bangalore, this is a charming murder mystery with echoes of Alexander McCall Smith’s stories. It isn’t all sweetness and light for the feisty young protagonist, newly married Kaveri. Married to a young doctor from a wealthy and prominent family, Kaveri misses mathematics lessons and swimming classes, and hates being lectured about social restrictions. While attending a party at the Century Club hosted by her husband’s English boss and his wife, she sees a woman being threatened by a stranger and spots other uninvited guests in the garden where she’s gone to have a quiet moment. Half an hour later, the party turns into a murder scene, and the finger of suspicion points at a defenceless woman. Kaveri’s soft heart and logical abilities insist that the woman is innocent and she sets about finding the killer. With a supporting doctor-husband backing her, she begins her investigation that takes her through different layers of Indian society—maalis and maids, brothels and exclusive clubs, and the huts and mansions of Indians and the British. We get a layered flavour of the everyday rhythm of life that dips into the inner lives and concerns of not just the wealthy, but also their staff. As the investigation delves deeper into societal taboos, Kaveri struggles to find her voice and speak out in a patriarchal society where a woman’s dreams can be only as big as their husband’s egos permit, a predicament that even 21st-century women continue to face. The charming cast, mouth-watering dishes—bisibelehuli anna, beans paliya, sweet corn and pomegranate kosambari—and a surprise recipe booklet (that slips out when we open the book) make for an enjoyable summer afternoon read.

FROM 1920S INDIA, I drifted to a quiet village in late-1980s England, with a gentle protagonist, a middle-aged bachelor-priest who has to find a killer among his flock. The congregation of St Mary’s Champton Rectory is up in arms over loos or more specifically whether it is permissible to build a loo in the place of a couple of back pews. Reverend Canon Daniel Clement, Rector of Champton church and his patron, Bernard De Floures of the De Floures Family, one of the Great Houses of England, back the loos. But the congregants in charge of arranging the flowers in the church have other plans for the space; they want to extend the flower room. Canon Daniel Clement discovers in the back of the church, the body of Churchwarden Anthony Bowness, a cousin of the De Floures, murdered with a pair of secateurs stabbed in the neck. Bowness has been conducting research into the De Floures family history, and Canon Clement wonders if the murder is linked to it. His investigation takes him into the dark secrets and deadly woes of his flock. While probing the inner lives of the suspect parishioners, Daniel, who lives with his 80-year-old widowed mother (an outspoken woman who lacks the ability to empathise) and two dachshunds, has to fend off a younger brother, a television actor who insists on shadowing him to prepare for a new role as a vicar. As we turn the pages, we learn more about the Reverend—he observes his flock’s sins with compassion, adapts to change, but also retains delightful idiosyncrasies. He writes with a pencil and his favourite kind of eraser is Faber-Castell’s latex free one “because it doesn’t leave a smear”. The quiet humour comes through in an exchange with a French visitor whose grandfather was billeted in the De Floures mansion during World War II. Daniel says regretfully: “I’m afraid their cuisine went with them. It’s very…rosbif here now.” One of the highlights of the book for me was its ruminative feel as we slip into the Canon’s world, a world of walks, prayer, sermons, continuing childhood rituals such as soup and sarnie night on Sundays, and ending each day with Compline at the threshold of night when “he felt closest to his parishioners”. He tells his brother, his life is one where “there is a lot of doing nothing,” but what we readers find is a rich inner life! Written by a real-life Reverend, Richard Coles, a clergyman and broadcaster, Murder Before Evensong is an immersive experience as we step off the fast-paced 21st century treadmill and soak up the charm of a bygone era and a delightful protagonist of a new series.