Sonia, an Uncritical View

Clearly, a book for a foreign readership by an ill-informed writer. Why foist this on us?

'Major Dalbir Singh, national secretary of the All India Congress Committee, was approached by a group of Sikh leaders once Sonia took over as Congress President. In 2002 a group of these leaders met with Sonia to ask her to visit the Golden Temple and to talk to her about outstanding issues to keep in mind should the Congress return to power. No president of the party had been to the Golden Temple in 16 years. The meeting started, but the leader of the Sikh delegation, sitting next to the Congress president, was star-struck and just stared at her, his jaw dropping, overcome with awe, as some Indians are when they meet her.'

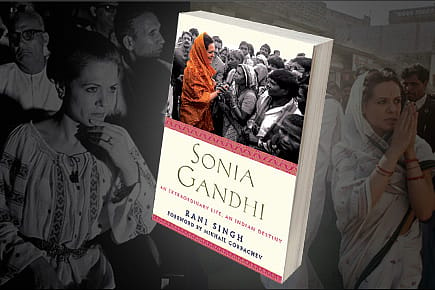

So goes the description of how Sonia Gandhi reached out to Sikhs in the book titled Sonia Gandhi: An Extraordinary Life, An Indian Destiny. And it illustrates perfectly the problems with this hagiography written by British journalist Rani Singh, who has worked largely with the BBC.

For one, the paragraph is factually incorrect. It was in 1999 that Sonia Gandhi as Congress President first visited the Golden Temple. I should know because I was there covering the visit for The Indian Express. As for the general awe that this Sikh delegation seems to have displayed, the fact remains she was very pointedly not granted the traditional honour of a saropa during this or her subsequent 2002 visit to the temple. The error both in fact and in interpretation are a result of relying solely on a source such as Major Dalbir Singh, who is the kind of person the Punjabi word 'jholachak' so vividly describes—someone who is often seen around politicians carrying their bags. This so-called biography is Sonia seen largely through the eyes of jholachaks, and the result should embarrass even the most fawning of Congressmen. Unbelievably, in the wake of the Radia Tapes, Vir Sanghvi is quoted over and over again without the question of his credibility being raised even once.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

The book, advertising itself as the first 'mainstream biography' of Sonia Gandhi, is clearly meant for a foreign audience and is more the pernicious for this reason. No critical view, no less-than-admiring evaluation, no blemish on the image of Sonia finds any real space in this book. Some of it could be naivete, but it clearly doesn't stop there. Sachin Pilot makes an entry in the book as a newly-minted MBA from Wharton, 'a part of Rahul Gandhi's age cohort, he and his inducted peers are serious individuals, frequently from political, royal, bureaucratic or business backgrounds, often with MBAs or some other degrees from an American or European university. They are driven, focused, and have an earnest desire to put something into their country'. The only thing the book doesn't say is something that every Indian knows but no foreign reader will guess—that Sachin Pilot is where he is because he is Rajesh Pilot's son. Such examples are numerous: Indira Gandhi's assassination and Rajiv Gandhi's ascent to power are vividly described, as is the massacre of Sikhs, but that the Congress was involved in the killings finds no mention, and neither does Rajiv's rather infamous comment on the violence.

Compare this with the earlier biography of Sonia written by The Telegraph journalist Rashid Kidwai, himself by no means unsympathetic to the Congress, and it is easy to see that the publishers and author really have no excuse for foisting such a book upon us. Kidwai's book is better informed about the workings of the Congress and machinations of Indian politics. At the end of almost 250 pages of text, the only new pieces of information I gleaned from Rani Singh's book is the presence of a cockroach in Rahul Gandhi's juice while he was in kindergarten, and how Sonia had dumped boiling spaghetti on the head of a young man trying to play a practical joke on her.

Such problems are exacerbated by the fact that this book seems to be unchanged in any way from the edition that was published abroad. In the very first paragraph of the preface, we are told that charpoys are 'wooden frames on four legs strung with rope', information that is repeated some 30 pages on. We are told that the Indian word for lentils is dhaal. We are told that 'enemies referred to Sonia as a vidayati murgi (a foreign-bred hen)' and this peculiar spelling of 'vidayati' is not an error on this magazine's part.

In essence, the book typifies the problem of what goes wrong when a Western publisher, however reputed, commissions a book on India, chooses a journalist, perhaps well known in the UK but clearly ill-informed about India, and then has the book vetted by editors and experts based in the West. The result is a disaster. Macmillan has only recently opened office in India; they would be far better served if they relied more on the opinion of the Indian editors they have hired. Bringing an edition published abroad unchanged to India is something that has been done often by other publishers in the past, but it has begun to grate. The extended explanations on things that most Indians know and take for granted sound patronising. If publishers are interested in the Indian market (they have no real choice, the economics of the business is driving them here), they need to be able to bring out an edition tailored to the requirements of an Indian reader.

But quite apart from publishing and the relationship between India and the West, the book is also unknowingly informative about the Congress and the culture that has been encouraged by its first family. This culture is akin to a medieval court, where people rise or fall depending upon their perceived loyalty. Everything is surrounded by the same kind of gossip and guesswork that today surrounds the state of Sonia's health. The lack of scrutiny by people who are not subservient, by media that is not overly keen to be seen as doing the party's or first family's bidding, means that accounts such as this, fed by those who only too clearly want to be seen as projecting Sonia in good light, will resurface. They do not do anyone credit.

Sonia is obviously a far more complex personality than this book makes her out to be, but unfortunately that is not a story that it seems will ever be honestly told.